Written by Dr. Josephine Livingstone

Medieval Europeans were fascinated by the lands that lay beyond their own continent. Josephine Livingstone looks at the real and imaginary travels of explorers and tradesman through works including The Book of John Mandeville, The Travels of Marco Polo and medieval maps.

From a 21st-century perspective – in an age of air travel and high-speed communications – it’s easy to imagine that medieval European people knew nothing of the world around them. People even use the adjective ‘medieval’ to indicate somebody who is backward-looking, barbarous or insular in their thought. But medieval Europeans were actually deeply engaged with lands beyond their borders. Often, that engagement was more creative than literal, taking place in texts and maps that were more influenced by literary history than by first-hand experience. But explorers and tradesmen ventured much farther afield in global space than our stereotype suggests, and from their travels, both real and imaginary, they brought cultural influences back with them.

‘Liber secretorum fidelium crucis’ by Marino Sanudo with maps by Pietro Vesconte, c. 1321. Explore this item further

The role of fiction and The Marvels of the East

Among the non-European lands known to medieval people, India was probably the most important. Europeans got most of their knowledge about the Indian subcontinent from the remnants of Greek learning, which had eroded over the centuries since the end of the classical period but survived in some Latin works. The earthly paradise was reputed to exist in or near India, at the farthest eastern edge of the world. Stories about Alexander the Great were particularly popular, having been handed down from the classical period. Alexander, the leader of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia in the 4th century, famously travelled all the way to India in his pursuit of power and lands. Many manuscripts describe his battles and adventures with fabulous creatures.

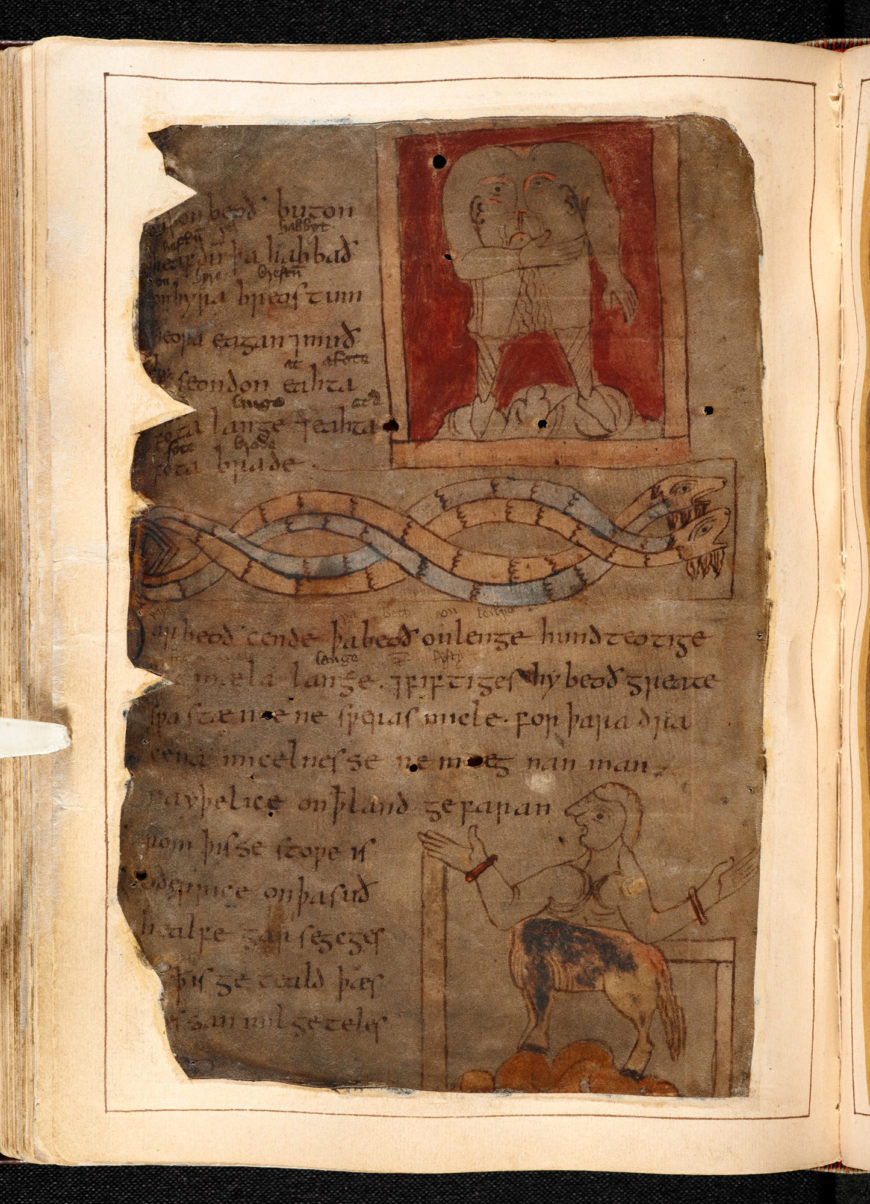

Latin sources gave medieval writers and map-makers a variety of options to draw upon when describing regions of the world. This array of sources, which did not always agree with each other, meant that new medieval writings blended easily into an already-varied culture. Writers such as the 3rd-century Julius Solinus, who drew on the works of Pliny the Elder, encouraged the idea that Asia and Africa were very hot places full of monsters and strange people: people without noses, or with giant feet to shade them from the sun, or with dogs’ heads, for example. The Old English The Marvels of the East is one such text that draws on these ideas, as well as those found in a hotchpotch of other Latin sources. Preserved in three manuscripts, including the book that contains Beowulf, this text describes and illustrates a vast range of strange and magical people and animals. Here you will find dragons, phoenixes and other familiar legendary creatures. But it also features people who are described as having ‘black’ skin, alongside other wonderful people who sleep curled up in their own enormous ears. Medieval Europeans’ view of people of different ethnicities was often bound up with wonder, fear and fiction.

The Marvels of the East is a fantastical account of the lands beyond Europe. This version appears in the same manuscript that also contains the Anglo-Saxon epic poem, Beowulf. Explore this item further

Medieval travel narratives: Marco Polo’s accounts of Asia and The Book of John Mandeville

While John Mandeville, Marco Polo and Odoric of Pordenone all wrote travel narratives in which they claimed to have seen a number of monstrous peoples, animals and cultural practices first-hand, the authenticity of these claims varied.

Marco Polo did, however, witness a great deal of what he wrote about. In the medieval period, the Polo family were among the greatest European travellers in Asia. Marco journeyed to China as a direct consequence of an earlier stay there by his father Niccolo and uncle Maffeo, who had set out from Constantinople in 1260 on a routine trading venture to Sudak in the Crimea. After this, they accompanied a caravan travelling along the Volga river to Sarai, the capital of Barka Khan, who was the lord of the western Mongols and grandson of Genghis Khan. In 1262, they got stuck in the region because of a war. While biding their time there, they received a request for an interview from the great Kublai Khan, who had never met any Europeans. He tasked them with taking a letter to the Pope to ask for 100 educated Christians to be sent to the court as missionaries. The only two people nominated for the task refused to go, so they took Marco, who was then aged 17, instead. He did not return to Venice until 24 years later.

In his Book of the Marvels of the World, also known as The Travels of Marco Polo, Marco describes many of the marketplaces he travelled through in terms of the strangeness of the business customs he sees, suggesting that they are unreasonable and difficult to understand. He accuses a Brahmin population of superstitions regarding a belief that business decisions could be influenced by the direction from which tarantulas enter a room. In one of the most interesting moments, he expresses delighted bafflement at the use of paper money at the Khan’s court. Marco Polo casts himself as a kind of imaginative bureau de change, a cosmopolitan Venetian embedded in a foreign court by his own choice.

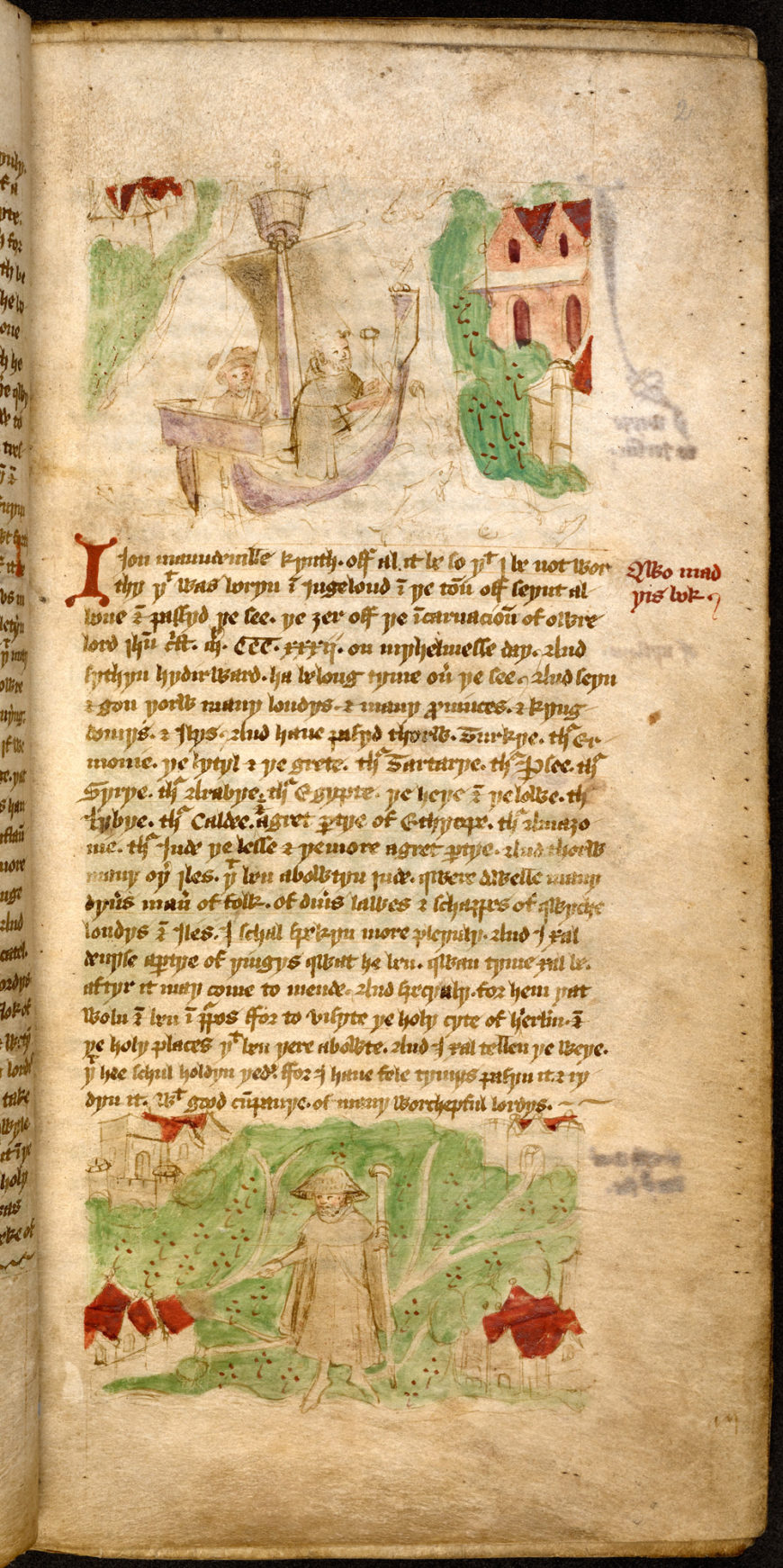

Unlike Marco Polo, the medieval ‘traveller’ John Mandeville is widely believed to have never existed at all. In the enormously popular text The Book of John Mandeville, the writer claims to be an English knight from St Albans. There is no evidence, however, to suggest that he really existed. His ‘book’ contains claims that John Mandeville was a soldier in the army of the great Khan, and that he had travelled far and wide in the East. There, the book relates, he came across all sorts of monstrous creatures and strange people, of the kind we might recognise from The Marvels of the East. This faux travel narrative was so popular that Leonardo da Vinci and Christopher Columbus both consulted copies, and its lack of authenticity, does not seem to have made a difference to the reception of the text. It survives in a staggering 300 manuscripts, and was translated into at least ten languages.

The Travels of John Mandeville purports to tell the story of one John Mandeville, a knight from St Albans in the south of England, who set of on a journey to the Holy Land and on to Asia and Africa in 1332. In fact Mandeville never existed and the account is a strange and fantastical description of a world away from Europe. Explore this item further

In the lives of real medieval people, global travel typically fell into the categories of religious pilgrimage, warfare (i.e. the conflicts often called the Crusades) or long-distance trade. From around the 8th until the 15th centuries, Venetian traders ran a virtual monopoly on trading with the Middle East and Asia. Materials including silk, herbs, spices and drugs travelled from South Asia over the Indian Ocean to the Middle East, where merchants transported them overland to Europe. Meanwhile, Western Europeans waged a series of wars against Muslim countries, aimed at limiting the expansion of Islam and the powers of its followers. These European powers framed their wars as spiritual conflicts: they were sending their soldiers to reclaim the Holy Land from Muslims. In the long term, Muslim control of formerly Christian lands such as Palestine and Syria remained firm.

Medieval map-making and Mappa Mundi

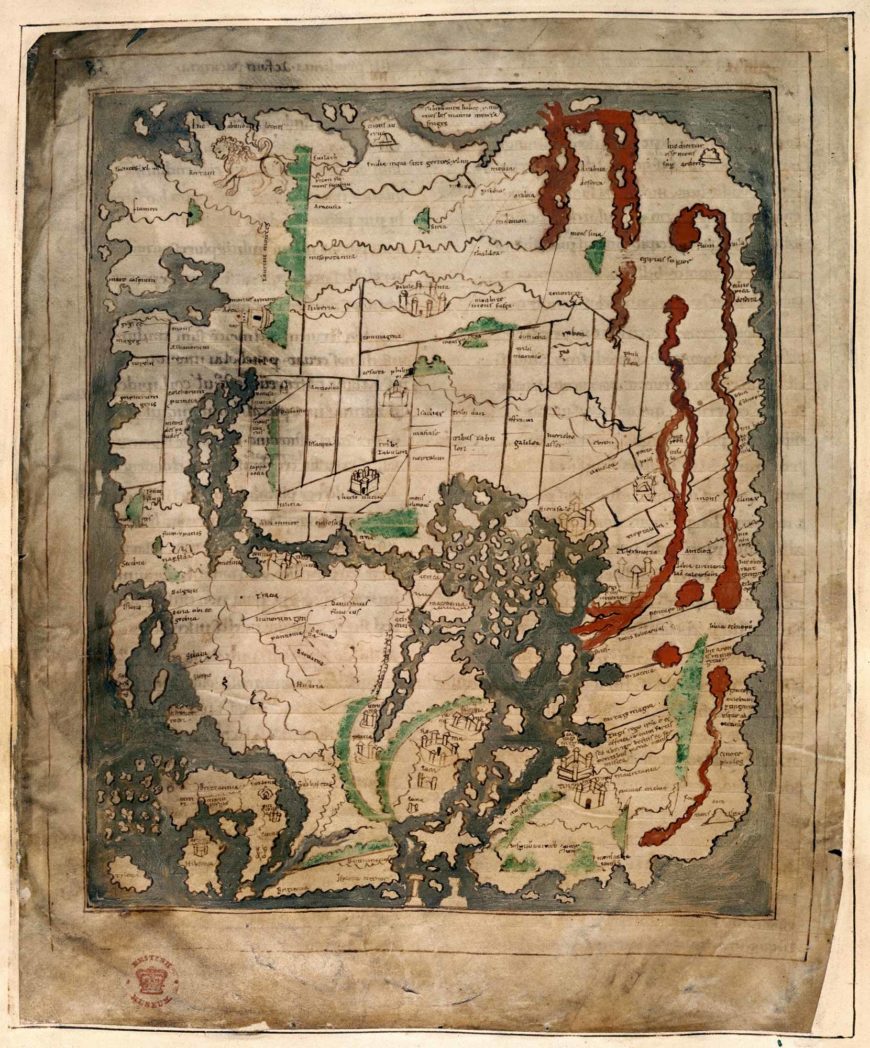

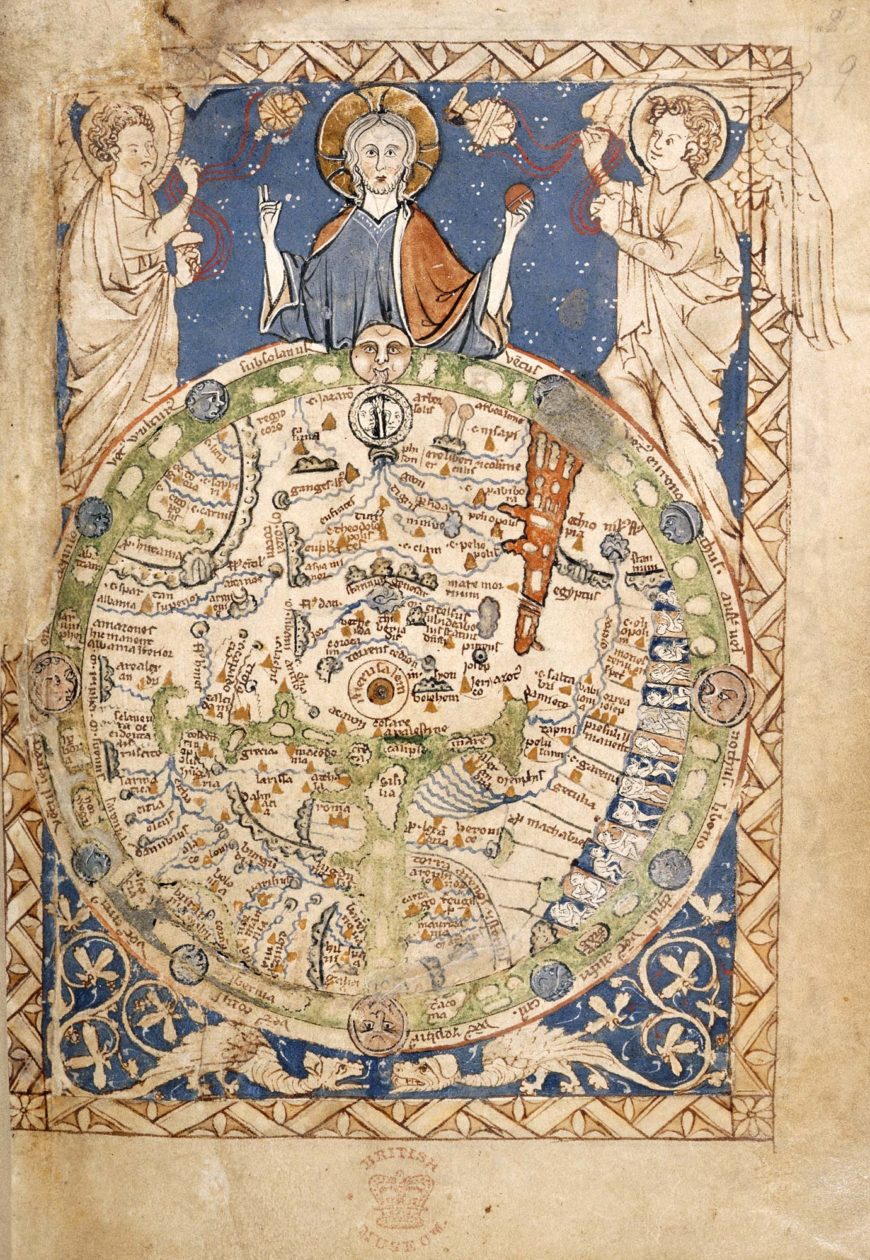

If a medieval person wanted to set out on a long, intercontinental journey, we might initially expect that they would consult a globe, or a world map. But the majority of the medieval maps of the world that survive today were not designed for travel; instead they contained information of spiritual and imaginative interest about the world. Some of the biggest examples hung in churches for the public to see, such as the Hereford Mappa Mundi which can still be found in that town’s cathedral.

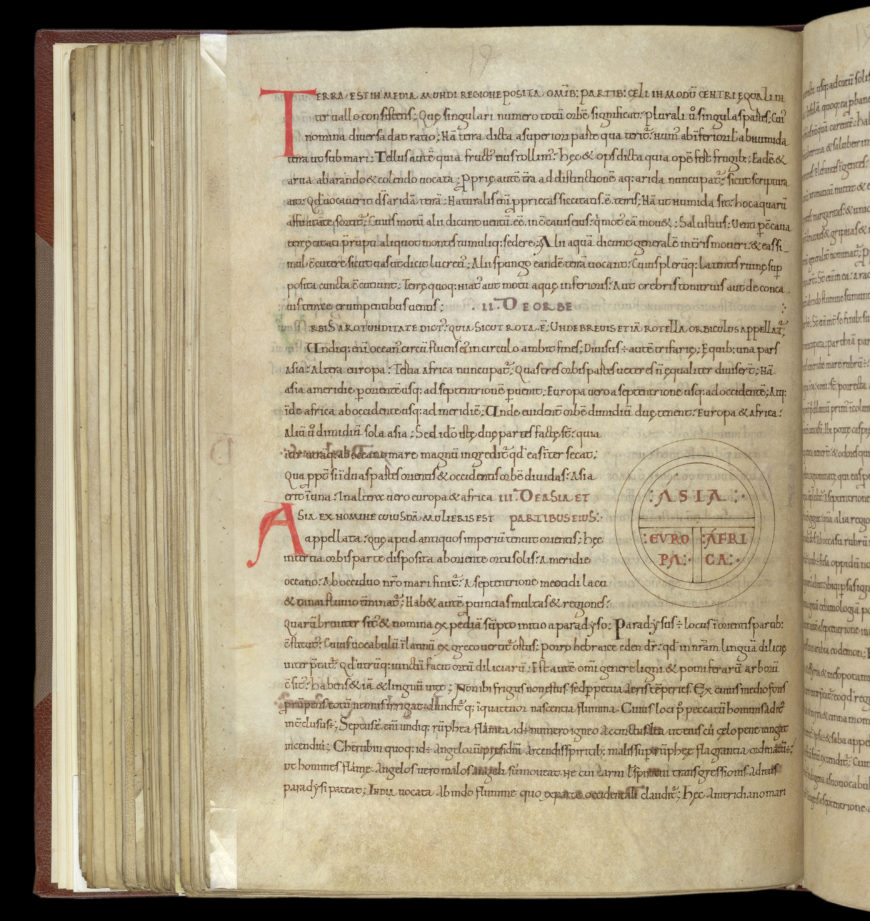

There are several types of these maps of the world, which scholars call mappa mundi. Around 1,100 or so survive, far fewer than the medieval literary manuscripts we still have. Medieval maps have east at their top rather than north, which is why we say that a map is oriented (oriens being the Latin word for east).

The majority of mappa mundi are versions of the Noachid form, named after Noah of the Old Testament. Each continent was supposedly founded after the Great Flood by Noah’s three sons – Shem, Japheth and Ham. These maps are also known as the wheel, tripartite or T-O form, so called because the outline of the world is depicted within the circle of an ‘O’ shape, which is divided into three continents by a ‘T’ formed by the waterways of the Nile, Mediterranean and Don. Many of these maps feature only this T-O shape, with no additional writing or drawings.

Anglo-Saxon Mappa Mundi. This map of the world was probably made in Canterbury between 1025 and 1050. Explore this item further

This map, dating from c. 1400 appears in a history of the world written by Ranulph Higden (d. 1364), who was a monk of the Benedictine abbey of St. Werburg, Chester. Explore this item further

Then there are the Macrobian mappa mundi, named after the Roman writer Macrobius, which divide the world into climatic zones. These maps impart less narrative content than other types of medieval map, but their climate zones link up with the environmentally deterministic medieval theories of race. The idea that the sun ‘burned’ the skins of Ethiopian people to a brown colour, for example, is expressed in the Old English retelling of the Exodus.

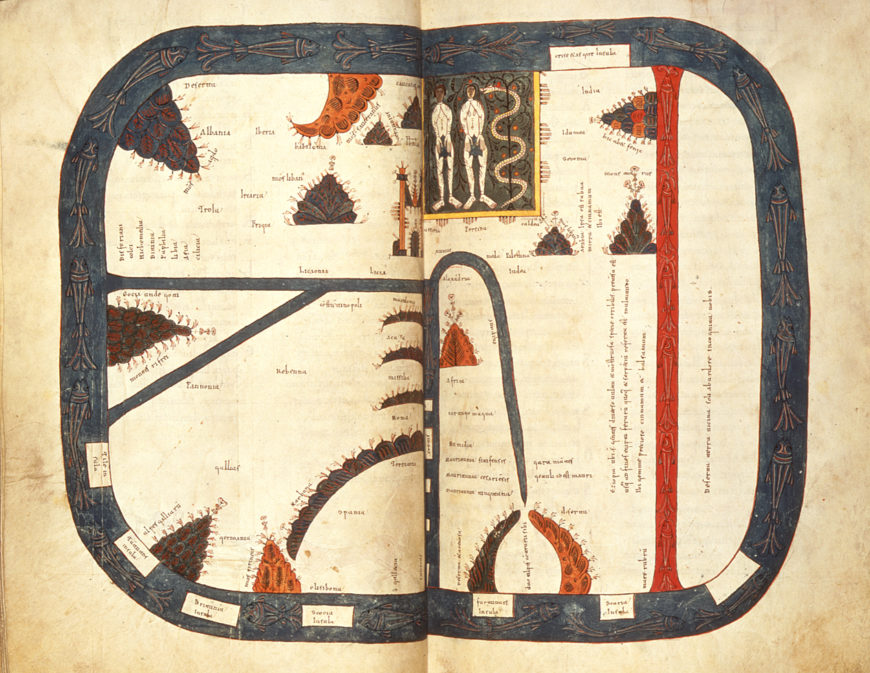

Beatus, or quadripartite maps, meanwhile, are not round at all – they are roughly rectangular, and show the journeys taken by the Apostles to evangelise the world.

This map is in the T-O form. It appears in an early 7th century work — the Etymologies by Isidore of Seville. The manuscript you can see here was made in the 11th century. Explore this item further

This map comes from the famous ‘Silos Apocalypse’ which was made in the Spanish Monastery of San Domingo de Silos in 1106. Explore this item further

There also survive a few large maps that we call the ‘complex’ mappa mundi, including the one that still hangs in Hereford Cathedral. These maps are usually roughly based on the T-O structure, but they are full of drawings, texts and other details that make them look more like huge narrative illustrations than maps as we would recognise today.

The Psalter World Map was made in London in the 1260s. Explore this item further

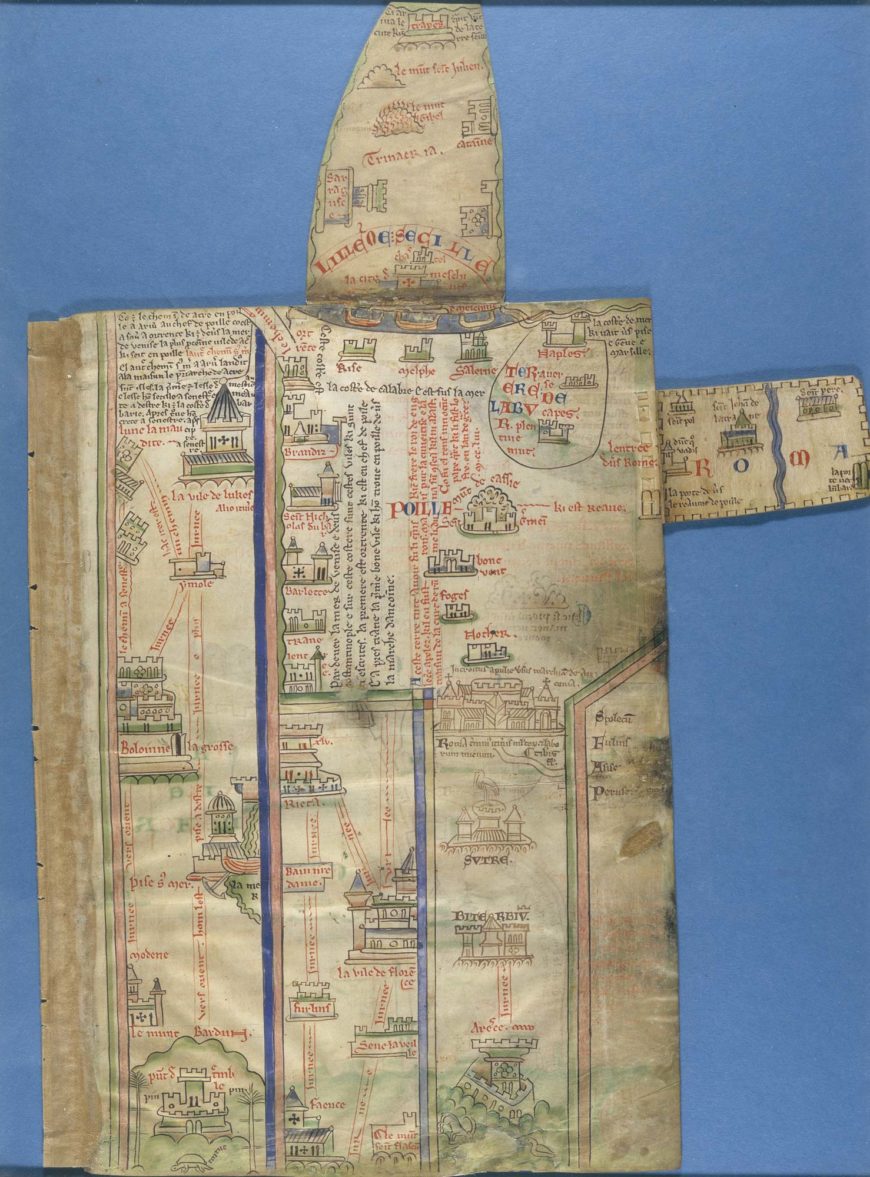

In the 13th century, a scholar in St Albans called Matthew Paris created a quite different type of map. He himself never left Britain, but he created a document showing an itinerary running from London to Palestine. His work is partly a map, partly a spiritual document and partly journey description. It is also a hybrid work of illustration and text. Although the book is in one sense a journey for the soul, it also features drawings of real places and things, such as castles, hills and trees.

Matthew Paris’s itinerary maps from London to Palestine. Despite having never been to Palestine, the monk and historian Matthew Paris (c. 1200–1260), created an itinerary from London to Palestine. Explore this item further

None of the medieval maps put Europe at their centre. Nor do the ‘travel’ literatures of medieval writers such as John Mandeville explicitly compare other cultures to European customs and ways of life. This is not to say that medieval Europeans were not ethnocentric, or Eurocentric. But medieval people thought of themselves in global space in a way that is subtly but importantly different to our geographical thought. Influences from the Bible and classical thought were strong enough to shape a medieval person’s view of themselves in the world. The boundary between textual and geographical thought on far-off places on earth was a porous one in the medieval period, and the wide world was very much a part of peoples’ lives.

Written by Dr. Josephine Livingstone

Dr Josephine Livingstone is the staff culture writer at the New Republic. Her PhD was in medieval literature and postcolonial studies, which she received from New York University in 2015. Her dissertation focused on race and landscape in late medieval poetry and maps. She has taught medieval literature widely in New York, but now focuses on cultural criticism as an “alt ac” practice. She still writes often about the medieval period, especially in the context of the alt-right.

Originally published by The British Library (CC BY-NC 4.0)