Porcelain was first produced in China around 600 C.E. The skillful transformation of ordinary clay into beautiful objects has captivated the imagination of people throughout history and across the globe. Chinese ceramics, by far the most advanced in the world, were made for the imperial court, the domestic market, or for export.

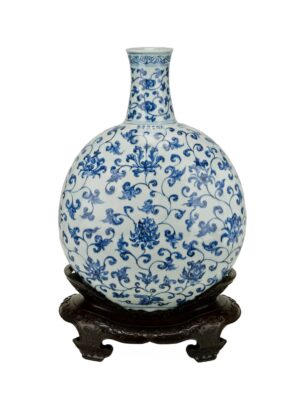

Large porcelain flask, c. 1426–35, Ming dynasty, Xuande mark and period, painted with underglaze blue decoration, Jingdezhen, 12 x 5.8 cm, China (© Trustees of the British Museum)

What is porcelain?

The Chinese use the word ci to mean either porcelain or stoneware, not distinguishing between the two. In the West, porcelain usually refers to high-fired (about 1300º) white ceramics, whose bodies are translucent and make a ringing sound when struck. Stoneware is a tougher, non-translucent material, fired to a lower temperature (1100–1250º).

Porcelain Ding ware bowl, Song dynasty, late 11th–early 12th century, Hebei province, northern China, 21.3 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

A number of white ceramics were made in China, several of which might be termed porcelain. The northern porcelains, such as Ding ware, were made predominantly of clay rich in kaolin. In southern China, porcelain stone was the main material. At the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province, kaolin was added to porcelain stone; in Fujian province, on the coast and east of Jiangxi, porcelain stone was used alone. The results differed in that northern porcelains were more dense and compact, while southern porcelains were more glassy and “sugary.”

Ceramics may be fired in oxidizing or reducing conditions (increasing or restricting the amount of oxygen during the process). Northern porcelains were usually fired in oxidation, which results in warm, ivory-colored glazes. Southern wares were fired in reduction, producing a cool, bluish tinge. An exception to this was blanc de Chine, or Dehua ware, from Fujian province, whose warm ivory hue came from oxidizing firings.

The export market

Chinese ceramics were first exported in large quantities during the Song dynasty (960–1279). The government supported this as an important source of revenue. Early in the period, ports were established in Guangzhou (Canton), Quanzhou, Hangzhou and Ningbo to facilitate commercial activity.

The ceramics trade established in the Song dynasty was maintained throughout the succeeding Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) and with a few interruptions, the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties as well. The markets were concentrated in different regions at different times, but the global influence of China’s porcelains has been sustained throughout. Within Asia, up until the fourteenth century, the potters of Korea imitated China’s porcelain with considerable success, and Japan’s potters did so for a still longer period. In the Middle East, the twelfth-century attempts to reproduce Chinese wares went on throughout the Ming period. In Europe however, porcelain was barely known before the seventeenth century. The English and Germans produced mass quantities of a similar hard-bodied ware in the eighteenth century.

Left: Scrolling lotus flask, Ming dynasty, Jingdezhen, China, 1426–35 (© The Trustees of the British Museum); right: Mosque Lamp, c. 1510, fritware, Iznik, Turkey (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Chinese porcelain influenced the ceramics of importing countries, and was in turn, influenced by them. For example, importers commissioned certain shapes and designs, and many more were developed specifically for foreign markets; these often found their way in to the repertory of Chinese domestic items. In this way, Chinese ceramics were a vehicle for the worldwide exchange of ornamental styles.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Additional resources

Learn more about the expanding the renaissance initiative.

Read more about ceramics developed around the globe that were influenced by Chinese blue-and-white porcelain, including:

- The Muradiye Mosque in Turkey

- Talavera poblana in Mexico

- Delftware in Holland