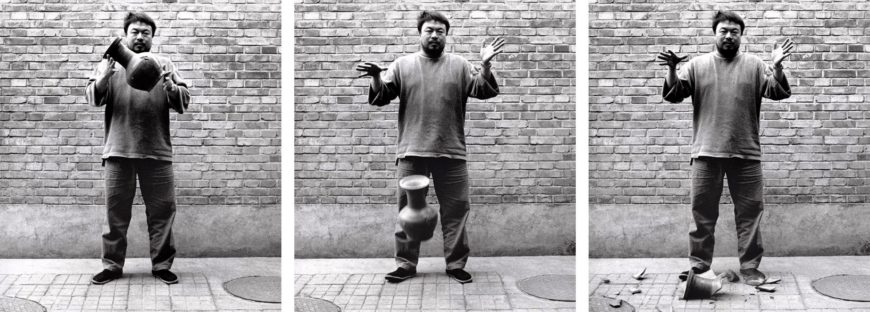

How can the destruction of an artifact also be an act of preservation? Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995) by Ai Weiwei is a highly provocative work of art. This series of three black and white photographs portray the artist holding a 2,000-year-old Han dynasty urn that, frame by frame, he drops, it falls, and shatters. As much a work of photography as a work of performance art, in each still an unaffected Ai looks directly at the camera aware of his destructiveness. In fact, to capture the action on film (rather than digital photography, which lets you review the image immediately), the artist actually broke two ceramic vessels, just in case. This kind of blatant destruction of artifacts may seem highly irreverent, yet it also forces viewers to consider issues of transformation and destruction of the past.

Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995 (printed 2017), Three gelatin silver prints, 148 x 121 cm each (photo: © Ai Weiwei)

Ai Weiwei

Born in Beijing, China, in 1957, Ai Weiwei is an activist, filmmaker, curator and one of the world’s most famous artists. Ai began his artistic career in New York City, where he lived from 1981 to 1993. When he returned to China in the mid-90s, a time of rapid modernization for his home country, he was shocked to discover that certain objects of cultural patrimony were not highly valued. Ai explains that when he came across these Han dynasty ceramic objects, they were just a dime a dozen: “I still have a photo of when I was in Xi’an. There was a farmer sleeping on top of these two urns waiting for someone to pay him a few hundred yuan. For him that was a few months’ salary, but even then nobody wanted them.” [1] Ai realized that during that period, most of his fellow countrymen were not nearly as interested in their country’s historic art objects as he was. For this reason, Ai began collecting antiquities, particularly ancient vessels and furniture, and eventually began converting these objects into contemporary artworks. Whether he reworks a discarded four-hundred-year-old wooden stool into a standing sculpture or creates an installation from hundreds of salvaged blue and white ceramic shards, Ai is interested in giving these historical found objects a second life as contemporary art.

Shang Dynasty jade from the tomb of Fu Hao, 1300-1046 B.C.E., Anyang, China (photo: © National Museum of China, Beijing)

Historical legacy

This kind of repurposing of the past also relates to Chinese aesthetics and culture. In China, there is a long and rarified tradition of collecting ancient material remains and transforming them into new art. For millennia before the advent of modern scientific archeology, rulers and elites collected ancient materials and acted to preserve them or emulate them in new works, whether it was preserving important documents by recording them on durable surfaces like stone steles or incorporating ancient designs into bronze or ceramics. For example, Fu Hao’s tomb in Anyang, a Shang dynasty (1600-1046 B.C.E.) royal burial tomb excavated in the 1980s, enabled scholars to push the history of antique collecting in China back to the thirteenth century B.C.E. The 775 jade carvings found in this tomb of a powerful Shang queen included both a collection of prehistoric jades as well a collection made in her era but modeled on earlier Neolithic prototypes. [2] This is an important revelation because it suggests that more than three thousand years ago, antique collections were already providing references and inspirations for making new works of art. This tradition of collecting and revitalizing antiquity has encouraged generations of Chinese artists and craftsmen to look to the past in making contemporary art.

Tomb of Fu Hao, late 13th century B.C.E., Shang dynasty, Anyang, China (photo: Gary Todd, CC0 1.0)

Act of revitalization?

Ai Weiwei has chosen an unusual way of continuing this legacy of transforming the material past while at the same time expressing dissent against a country that sometimes obliterates its own cultural heritage: through direct confrontation. On the one hand we can view his work as a destruction of another artist’s work; on the other, Ai’s act can also be thought of as a kind of collaboration with an ancient artist over thousands of years—a revitalization. Once an ancient receptacle, the urn in Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn takes on new meaning as contemporary art. In Ai’s work, the object is less a vessel than an emblem of Chinese history. For this performance, it seems that the object selection is almost immaterial—it might as well have been any ancient object. However, in recognition of Ai’s own celebrity, the artist has transformed this urn into something of great significance just by selecting it to become the subject of his art, by including its name in the title, and, of course, by destroying it. The sensationalism of breaking something so old and rare is what modern audiences find so compelling. Here the nostalgia for what once was serves as a mirror, reminding us that China’s past remains important and relevant today.

Destruction as preservation

The event that Ai Weiwei created and captured in these photographs is one of violence. Many feel that it is unethical to destroy an artifact under any circumstances—that such an act indicates a lack of value and respect. Indeed, law professor Joseph Sax calls such destruction a kind of “unqualified ownership” because it enables “the indulgence of private vice to obliterate public benefits.” [3] Certainly, the destruction of art for ideological or egoistic reasons reflects badly on a collector of ancient objects. Yet was Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn a true obliteration? The Han dynasty urn still exists for the public but it has been transformed into the form of captured film stills. The loss of one object gives the new artwork its potency.

Ai Weiwei “According to What” exhibition, Art Gallery of Ontario, (photo: Joseph Morris, CC BY-ND 2.0)

Ai himself says that he considers the act of dropping the urn one of creation rather than destruction: “People always ask me: how could you drop it? I say it’s a kind of love. At least there is a kind of attention to that piece [because of the photograph].” [4] From the artist’s point of view, his act was one of preservation through transformation. Indeed, this triptych (set of three photographs) and the shadow of the vessel captured within it now receive unprecedented attention. These photographs are displayed in museums and public institutions around the world. The work is widely available online, and even the focus of academic essays like this one. Given Ai’s own celebrity status and the significance of this artwork, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn is also now far more valuable than the original ceramic object. In 2016, this limited edition work sold for nearly 1 million dollars at Sotheby’s Auctions in London. [5]

Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn is one of many works by Ai Weiwei that focuses on heritage loss and the importance of the past. According to the artist, “the power [of my artwork] comes not from the act but from the audience’s attention, the challenge to their values. The act is easy—every day we can drop something, but it is when we are forced to come face to face with this action and make a judgment … that is the interesting part.” [6] Ultimately the work demands a judgment: was the provocation and the global attention Ai garnered for the urn worth the destruction of the urn itself? This set of photographs encourages its viewers to question value of antiquity in our modern world and whether it is worth preserving.

Notes:

- Tiffany Wai-Ying Beres, “A Battlefield of Judgments: Ai Weiwei as Collector,” Orientations 46, no. 7 (2015), pp. 87–92.

- Wu Hung, ed., Reinventing the Past: Archaism and Antiquarianism in Chinese Art and Visual Culture (Chicago: Art Media Resources, 2010), pp. 16–39.

- Joseph L Sax, “Collectors: Private Vices, Public Benefits,” in Playing Darts with a Rembrandt: Public and Private Rights in Cultural Treasures (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011), p. 63.

- Beres, p. 92.

- Sotheby’s Auction: https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/lot.42.html/2016/contemporary-art-evening-auction-l16020

- Beres, p. 92.

Additional resources: