Several members of the cast of the film The Monuments Men made headlines for expressing the view that the British Museum should return the Elgin Marbles to Athens after their “very nice stay” of 200 years in London.

That reignited the debate around the ethics and intentions of their removal from the Parthenon in the early 19th century, as well as the controversy around what to do with them now. But whether or not the removal of the sculptures should be considered “pillage or protection”, as the Guardian put it, we might take the opportunity to reflect on other more contemporary and unambiguous examples of international cultural heritage plunder.

Demands of the art market

The international art market that deals in ancient cultural objects casts a destructive shadow. Tombs are looted, statues broken from their pedestals, and facades chainsawed off temples, all to feed a booming economic demand among connoisseurs who prize the enjoyment of the artistic attributes of cultural objects, the thrill and investment value of collection, and the social status attributed to those associated with high culture.

The source countries for these collectible objects tend to be less economically developed than the market countries and so are usually not very well equipped to protect their heritage resources against plunder. London and New York are the two biggest centers for this trade in the world, and their active art markets have over the years exerted a strong demand for the archaeological riches underground in countries like Egypt, Greece and Turkey; or pieces of temple complexes like those found in South America and South East Asia.

Bronze statue of a nude male figure, Greek or Roman, Hellenistic or Imperial, c. 200 B.C.E.—c. 200 C.E., bronze (on loan to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and possibly looted from the ancient site of Bubon in Turkey)

Estimates of the size of the illicit underworld of the international trade in art and antiquities are unreliable at present. Although figures as high as US$6 billion have been proposed, it is generally recognised that it is currently impossible to verify size estimates. Many looted antiquities are sold on the open market and their illicit origins will never be detected, let alone proved. And, as well as the public trade through auction houses and museum acquisitions which can be scrutinised to some extent, there is also a private trade between individuals, which is difficult to investigate.

Police statistics in most countries do not even have a separate category for art related thefts or seizures. They tend to lump them in with all other types of property theft. Looting in source countries happens at sites which are often remote, and in some cases undiscovered, and much looting activity is not detected or recorded by over-stretched local police forces.

All of these factors, and more, make it very difficult to know how much illicit market activity there really is. But a growing body of research has established considerable evidence to show that looting and trafficking is still a sizeable and serious issue, and one involving significant sums of money.

Cultural looting

There was a relatively uncontested free and open dealing in looted cultural objects in Britain and elsewhere running through the colonial era, supported by imperialist values, and this continued. Then, in the 1960s a sustained critique of these practices began to take hold.

Archaeologists who had experienced first-hand the looting of sites they had been working on began to reflect on the rapacious nature of the market in cultural resources. In particular, they argued that looters destroyed sites as they dug out tombs and other underground heritage, depriving researchers of the historical knowledge which the context of buried objects could give up.

Criticism of the international trade in looted antiquities mounted, and in 1970 UNESCO brought countries together under an international convention to protect the world’s cultural heritage from exploitation by market forces. This date of 1970 has over time come to be accepted as the norm for acquisition of antiquities, particularly among museums subscribing to a collective ethical code.

They now have to look for a “provenance” (ownership history) dating back to at least that date. This is obviously therefore a rule intended to reduce demand for artifacts looted in recent decades, rather than to right any perceived wrongs of a more historical nature. But not all types of buyers in the market subscribe to the 1970 norm – and our research evidence suggests the “1970 rule” is not greatly influencing aggregate buying decisions in public market settings.

Repatriation

Major dealing and collecting institutions have been implicated in the trade in illicit cultural objects, as one would expect, given that traffickers have inserted looted artifacts into the legitimate trade, where they have most value. And as the understanding of the reach of this increases, so does the trend towards “repatriation” of objects to their source countries from the world’s encyclopedic museums.

For example, in 2013 the Metropolitan Museum in New York returned two “Kneeling Attendants” to the national museum in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, looted originally it seems from the temple complex at the ancient Khmer capital of Koh Ker, one of Cambodia’s great heritage sites.

Koh Ker National Park, Cambodia (photo: Bruno Schoonbrodt, CC BY-NC 2.0)

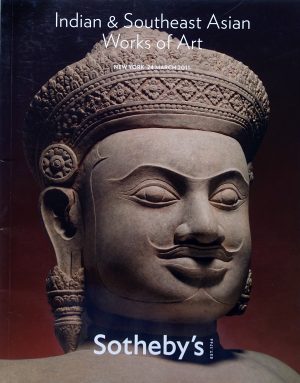

At the same time, another statue from Koh Ker has been the subject of litigation in the New York courts: the Duryodhana, offered for sale by Sotheby’s for an estimated $2m-$3m. The statue in New York was broken off at the ankles and its feet were discovered still attached to their pedestal in the Prasat Chen temple at Koh Ker.

At the same time, another statue from Koh Ker has been the subject of litigation in the New York courts: the Duryodhana, offered for sale by Sotheby’s for an estimated $2m-$3m. The statue in New York was broken off at the ankles and its feet were discovered still attached to their pedestal in the Prasat Chen temple at Koh Ker.

The US Department of Justice alleged that it was torn from its base in the 1970s during the civil war which led to Khmer Rouge power – and from our fieldwork in Cambodia, we have first-hand accounts of similar looting activity from traffickers active at that time. Subsequently, it was transported to London where it was sold to a Belgian collector through the auction house Spink. Late in 2013, Sotheby’s and Cambodia concluded a settlement to the case, and the statue was returned.

The pressing question for the great museums of the world is what will happen to their repositories in a climate of greater attention to the ethics of acquisitions, present and past. This raises difficult value judgements around the wider issue of where ancient artifacts belong, the moral status of major museums in rich countries, and “who owns culture”, as the titles of several books in the field put it.

For some people, this question may invite different responses when applied to cases like the Elgin Marbles on one hand, or fresh loot on the other. For so-called “cultural internationalists,” the issue is the very moral legitimacy of countries declaring ownership of all cultural heritage. But the countries themselves would see the moral and legal elements of their title as being settled.

Market victim or complicit?

The extent to which museums, dealers, collectors and auction houses know about the illicit origins of objects they acquire – and whether they turn a blind eye or are genuinely duped by fraudulent sellers – is hotly contested. The New York dealer Frederick Schultz, for example, once president of the National Association of Dealers in Ancient, Oriental and Primitive Art, was sentenced in 2002 to nearly three years in jail and received a $50,000 fine for his part in receiving looted items from Egypt through a British smuggler named Jonathan Tokeley-Parry.

The smuggled objects had been dipped in plastic and painted to look like tourist souvenir items, thus evading Egyptian border control. The two dealers then fabricated provenance for the items in order to give them the appearance of having a legitimate ownership history, inventing a collector they called Thomas Alcock and attaching labels to the objects to suggest they were from his collection.

They even went so far as to artificially age the labels by dipping them in tea, to better support the illusion they were creating. The artifacts included a sculptural head of the 18th dynasty pharaoh Amenhotep III, subsequently to be sold by Schultz for $1.2 million.

And in 1997, journalist Peter Watson published the results of his five-year investigation Sotheby’s: the Inside Story, which alleged complicity among some of the auction house’s employees in knowingly receiving looted and trafficked artifacts.

Subsequently, Sotheby’s closed the London arm of its antiquities sales department, never to re-open, in a move which was “widely interpreted” as a response to Watson’s book, and which prompted Boston University archaeology professor and long-time commentator on illicit trade issues Ricardo Elia to note that “London has been called the smuggling capital of the world.”

Against these scandalous examples of malpractice, trade representatives tend to argue that they exercise appropriate levels of “due diligence”. Criminal offenses for dealing in illicit cultural objects like the up-to-seven year prison sentence created in the UK in 2003 often require the prosecution to prove a buyer’s “knowledge or belief” of an object’s tainted history, which has proved very difficult to do. The UK law remains virtually unused.

And so the current debate raised by George Clooney, Matt Damon and Bill Murray’s thoughts on the repatriation of the Elgin Marbles is important, but for reasons which don’t tend to make their way into press reports of the controversy. The discussion around antiquities which were taken from Greece over two centuries ago is part of the context of a more immediate issue of global crime. Looting and trafficking of cultural objects is not only a problem of the past.

![]()

by Simon Mackenzie, Professor of Criminology, Law and Society, University of Glasgow (CC BY-ND 4.0)

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.