Views of Rome have long fired human imagination, eliciting reactions that lead to contemplation and argue for conservation.

Views of Rome

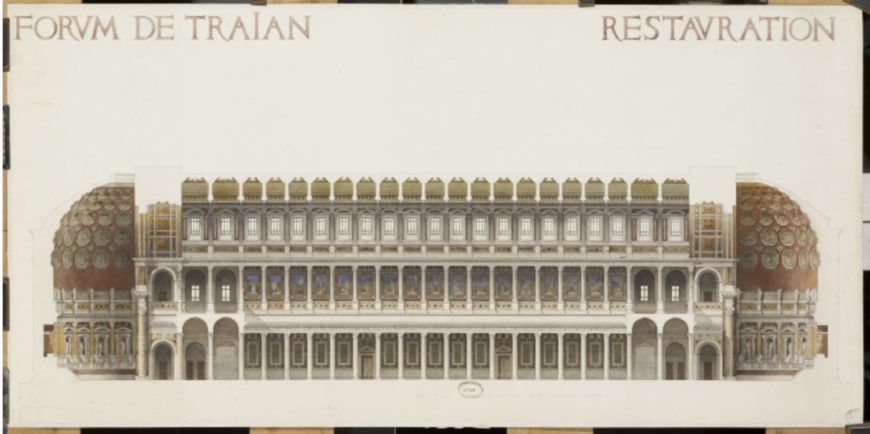

The Roman emperor Constantius II (the second son of Constantine the Great) visited Rome for the only time in his life in the year 357 C.E. His visit to the city included a tour of the usual monuments and sites, but the majesty of the Basilica Ulpia still standing in the forum built by the emperor Trajan arrested his attention, causing him to declare that the monument was so grand that it would be impossible to imitate it (Ammianus Marcellinus Rerum Gestarum 16.15). From a certain point of view, any visitor to Rome can share the experience and reaction of Constantius II.

Reconstruction of the Basilica Ulpia, Julien Guadet, “Memoire de la restauration du Forum de. Trajan,” manuscript No. 207 dated 1867, Ecole des Beaux-Arts,. Paris 21-23

The city’s monuments (and their ruins) are cues for memory, discourse, and discovery. Their rediscovery and subsequent interpretation in modern times play a key role in our understanding of the past and influence the role that the past plays in the present. For these reasons, among others, it is crucial that we think critically about fragmented past landscapes and that any reading of fragments is contextualized, nuanced, and transparent in its motives. The physical presence of fragments raises the question of whether or not the past is knowable. Tangible ruins and artifacts suggest that it is, but whose story are we telling when we analyze and interpret these remains? If we consider a quintessentially famous and evocative archaeological landscape like the Forum Romanum (Roman Forum) in Rome we have an opportunity to examine a fragmented past landscape and also to explore the question of what role archaeology plays in understanding and interpreting the past.

Detail, Giovanni Paolo Panini, The Archaeologist, 1749, oil on canvas, 123 x 91 cm (National Academy of San Luca, Rome)

From heart of empire to pasturage for cows

The story of the Forum as an important node of cultural significance was central to ancient Roman ideation about their city and even themselves. Romans could define themselves in relation to the places where they believed key past events had occurred. The fact that this tradition provided the backdrop for the Forum’s activities works to heighten the efficacy and the value of constructing collective identity and memory. In ways both practical and symbolic the cramped space sandwiched between the Capitoline and Palatine hills was the heart of the Roman populace.

View of the Roman Forum, with the Arch of Septimius Severus, left, and the Column of Phocas at center (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The Forum witnessed many of the city’s key events. It began as a central point of convergence in the landscape for sacred and civic business and, over time, became a sort of monumentalized and petrified museum of the offices of state and the promotion of state ideology. With the decline of the western Roman empire in the 3rd and 4th centuries C.E., the relevance and importance of the forum square receded. Its structures fell into disuse, were stripped of usable building materials, and repurposed for other uses.

The last purposefully erected monument of the forum is the so-called Column of Phocas, a cannibalized column (it was originally made for another monument). It was erected on August 1st of 608 C.E. in honor of the Eastern Roman Emperor Phocas. Its inscription (CIL VI, 01200) speaks of eternal glory and lasting recognition for the emperor (a statement on monumentality that had long echoed in Latin literature, for instance, Horace Odes 3.30). It is not insignificant that in a much diminished city of Rome it was nonetheless worthwhile to create a new monument (even if using repurposed materials) in the once thriving sacred and civic center of the city.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Modern Rome—Campo Vaccino, 1839, oil on canvas, 91.8 x 122.6 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum)

A ninth century guide for Christian pilgrims in Rome (known as the Einsiedeln Itinerary) notes that the forum had decayed from its former glory. It is likely that, as a landscape of disuse and re-use, the forum had by that time morphed into a form that perhaps would be scarcely recognizable today. The central square came to be used as grazing land, earning it the nickname “Campo Vaccino” or “cow field” by the Middle Ages.

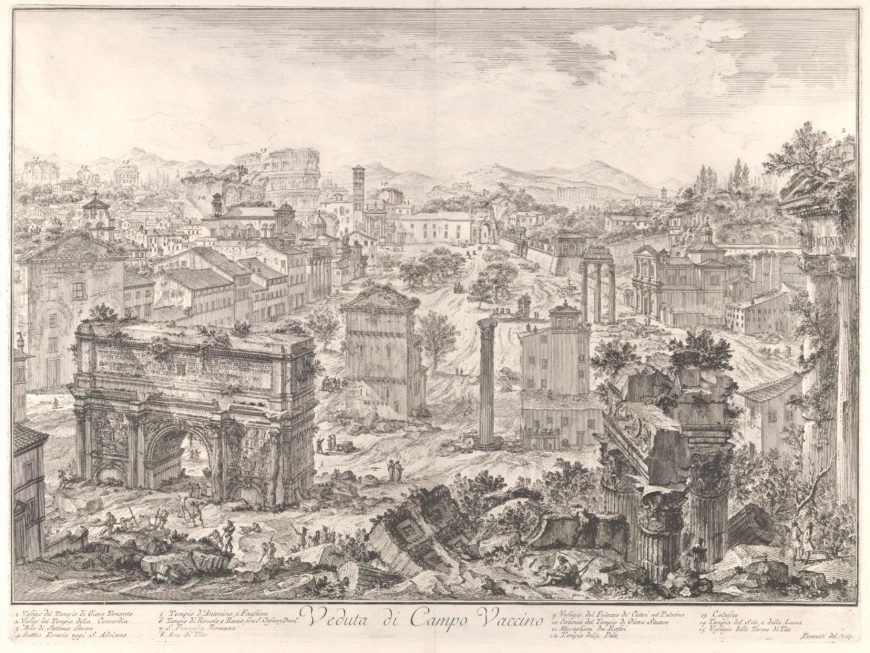

This broken landscape of abandoned and discarded structures and monuments evoked the past and provoked the fancy and imaginations of viewers. It appealed particularly to artists who were keen to craft a romantic vision of the broken pieces of the past set amid the contemporary world. This romantic movement produced a genre of art in various media in the eighteenth century that is often referred to as vedute or “views”.

Giovanni Paolo Panini, Modern Rome, 1757, oil on canvas, 172.1 x 233 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Painters the likes of Giovanni Paolo Panini produced vedute of ancient and contemporary Rome alike, often enlivening his canvases with contemporary human figures and their activities. In these “views” one can appreciate the creation of an assemblage, one that juxtaposes ancient elements with contemporary elements and human figures. The work of Panini and his contemporaries creates a romantic view of the past without being concerned overly with objectivity.

In the same century the artist and engraver Giovanni Battista Piranesi was also active. Piranesi’s approach to the ruins of Rome alters the course of the field, not only in terms of artistic representation but also in terms of how we approach the ruins of past civilizations. One part of his oeuvre focuses on renderings of the ruins of Rome set amidst contemporary activity. The fragments of the past are very much the focus—their massive and monumental scale cannot help but capture the viewer’s attention. Despite the expert draughting of Piranesi, the ruins—being incomplete—remain a topic worthy of inquiry, as something of them is unknown.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Vaccino, from the capitol, with the Arch of Septimus Severus in the foreground left, Temple of Vespasian right, and the Colosseum in the distance (Veduta di Campo Vaccino), c. 1775, etching (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The work of Panini, Piranesi, and others in the eighteenth century shows us that views of Rome are not just flights of fancy or imagination, but rather they are connected to memory. Piranesi was influenced in his early years by mentors interested in the revival of the ancient city as well as by others (namely Giambattista Nolli), who aimed to record the ancient remains in fine-grained detail. Piranesi, then, brings an expertise born from the school of the Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio that is combined with an enthusiasm for Rome as the locus classicus of “old meets new.” The curation of views of the ancient remains not only reinforced shared memories of a past time but, also reinforced memory in contemporary terms.

Depicting ruins as fragile yet once powerful monuments might suggest that lessons derived from the past might help one to avoid the collapse and decay that is of course inevitable. These depictions of Rome’s past, encoded with memory, are important to the artistic culture of the eighteenth century and foreshadow what the nineteenth century will bring.

A disciplinary revolution

The nineteenth century witnesses a number of changes that in some cases move the conversation away from subjective romanticism and toward a more methodological approach to science and natural science. The discipline of archaeology emerges from this movement and, as with any new undertaking, the discipline needed to sort itself out in order to embrace a set of practices and norms. Antiquarians abounded but archaeologists were relatively new, even though early pioneers like Flavio Biondo (15th century) likely numbers among the first archaeologists.

The nineteenth century was a momentous time for archaeology at Rome. The archaeologist Carlo Fea began an excavation in the Roman Forum to clear the area around the third century C.E. triumphal arch of the emperor Septimius Severus. Fea’s work ushers in a new era of what would become archaeological practice in the valley of the forum, as well as at other sites of the ancient city. Interest grew in decluttering or isolating the ancient moments. As the methods of archaeology developed, more scientific rigor could be observed.

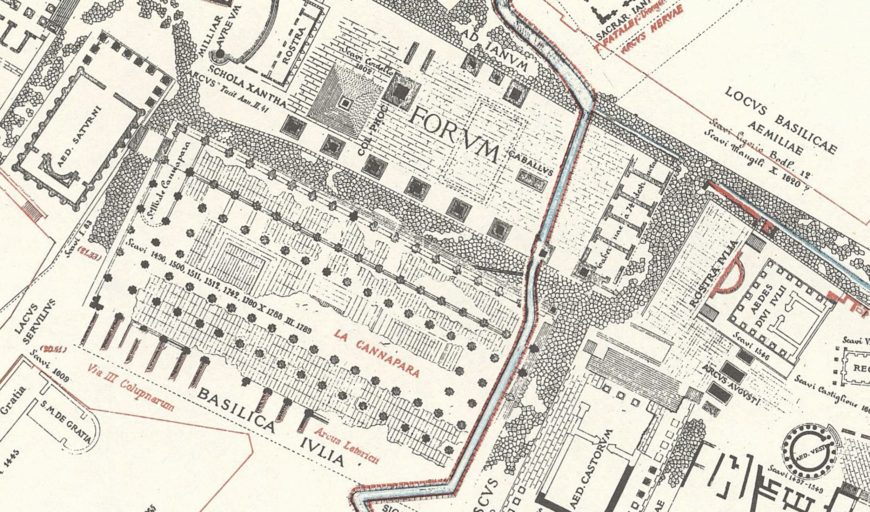

The Roman topographer Rodolfo Lanciani was a disciplined and active excavator at Rome. His magnum opus was the Forma Urbis Romae (1893–1901), a map at a scale of 1:1000 of the city of Rome, noting both ancient and modern features. It evoked earlier maps of Rome (for example the 1748 map produced by G. Nolli), but also reached back to the Severan marble plan of the third century C.E. in representing in detail the city and its monuments. One might see Lanciani’s Forma Urbis as a development that grew from the same tradition in which artists like Panini and Piranesi had worked—one could appreciate views of Rome, and, in so doing, gain a command of the sites and the memories linked to them.

Giacomo Boni in the Roman Forum in front of the Arch of Titus, Rome, Italy, from L’Illustrazione Italiana, Year XXXIV, No 7, February 17, 1907

At the turn of the twentieth century the excavations of Giacomo Boni in the Roman Forum were transformational, not only because they represented an enormous methodological advance for the time but also because they set the tone for archaeology in the forum thereafter. Boni’s stratigraphic excavations sampled previously unexplored layers of the city’s past and exposed the Roman Forum not just as a cow pasture with a few random columns protruding from the ground but as a complex cultural and chronological laboratory.

Some of the trends established in Boni’s time continued in the period of Italian Fascism (1922–1943) when archaeology showed a clear bias for the late Roman republican period and the principate of the emperor Augustus (31 B.C.E–14 C.E.). It was hoped that these earlier periods of perceived cultural, legal, and moral greatness would be examples that a modern Italian state could emulate. For this reason those archaeological strata were privileged, while others that were deemed unworthy were haphazardly destroyed in order to reach the preferred time period. In many ways these disciplinary choices were unfortunate and they do not find a place in twenty-first century archaeological practice. Nonetheless they shaped the landscape of the Forum valley that confronts us still day—one that is incomplete, at times chronologically incongruous, and evocative of an obviously complex past.

Contextual landscapes and fragments

Today the Roman Forum is part of a protected archaeological park that includes the Palatine Hill and the Colosseum. It is a site of significant popular interest and is visited by millions of tourists annually (7.6 million in 2018). It is also the site of ongoing archaeological research and conservation. The Forum is a challenging site to understand, both in terms of its chronological breadth and in terms of the processes of its formation (including archaeological excavation) that have shaped it.

The Forum should make us think about the goals of archaeology and the importance of archaeological context. One of the alluring things about the Forum is that it is fragmentary and incomplete. Latin authors were wont to mock the futile vanity of the potentates who sought to achieve immortality through the construction of monuments since those same monuments would inevitably decay. Their critique touches on a point that is central to a consideration of a fragmentary landscape like the Roman Forum, namely that the development of the space over time represents not just multiple time periods and historical actors but also multiple conversations between the space and the viewer.

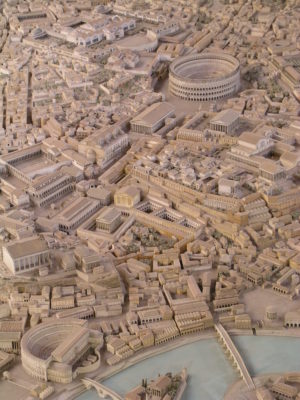

Model of ancient Rome in 1:250 by Italo Gismondi

The discipline of archaeology, in some respects, seeks to reassemble the past and it can only do this via contextual information. This means that the archaeological record needs to be preserved to the extent possible and then be interpreted in a rigorous and objective fashion. The impetus to reassemble what is broken informs our practice in many ways. It certainly influenced Lanciani’s plan of the city of Rome and Italo Gismondi’s model of the same. Scholars in the later twentieth and twenty-first centuries have similar motives, whether architect’s reconstruction drawings (see Gorski and Packer 2015), or a new archaeological atlas of the city inspired by Lanciani (see Carandini et al. 2012) or even 3D virtual renderings as in the case of the “Rome Reborn” project.

Our conversation with the Forum Romanum continues. In early 2020 there was a great deal of excitement about a re-discovery in the area of Giacomo Boni’s early twentieth century excavations. The site, perhaps connected with the cult of Rome’s traditional founder Romulus, provided an opportunity for a conversation that was both new and old at the same time.

Our views of the fragmented landscapes of the past are vital to our understanding not only of the humans who went before us but also, importantly, ourselves.

Additional Resources

ANSA news agency. “Hypogeum with sarcophagus found in Forum. Near Curia, dates back to sixth century BC.” February 19, 2020.

ArcheoSitarProject – SISTEMA INFORMATIVO TERRITORIALE ARCHEOLOGICO DI ROMA

Ferdinando Arisi, Gian Paolo Panini e i fasti della Roma del ’700 (Rome, 1986).

J. A. Becker, “Giacomo Boni,” in Springer Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, edited by Claire Smith (Berlin, Springer, 2014). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_1453

Mario Bevilacqua, Heather Hyde Minor, and Fabio Barry (eds.), The serpent and the stylus: essays on G.B. Piranesi, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome,

Supplementary volume 4, (Ann Arbor, Mich.: Published for the American Academy in Rome by the University of Michigan Press, 2007).

Mario Bevilacqua, “The Young Piranesi: the Itineraries of his Formation,” in Mario Bevilacqua, Heather Hyde Minor, and Fabio Barry (eds.), The serpent and the stylus: essays on G.B. Piranesi, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, Supplementary volume 4, (Ann Arbor, Mich.: Published for the American Academy in Rome by the University of Michigan Press, 2007) pp. 13-53.

R. J. B. Bosworth, Whispering City: Rome and Its Histories (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011).

Alessandra Capodiferro and Patrizia Fortini (eds.), Gli scavi di Giacomo Boni al foro Romano, Documenti dall’Archivio Disegni della Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma I.1 (Planimetrie del Foro Romano, Gallerie Cesaree, Comizio, Niger Lapis, Pozzi repubblicani e medievali). (Documenti dall’archivio disegni della Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma 1). (Rome: Fondazione G. Boni-Flora Palatina, 2003).

Andrea Carandini et al. Atlante di Roma Antica 2 v. (Milan: Electa, 2012).

Filippo Coarelli, Il foro romano 3 v. (Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 1983-2020).

Digitales Forum Romanum (Humboldt University)

Catherine Edwards and Greg Woolf (eds.) Rome the Cosmopolis (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Don Fowler, “The ruin of time: monuments and survival at Rome,” in Roman constructions: readings in postmodern Latin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000) pp. 193-217.

Gilbert J. Gorski and James Packer, The Roman Forum: a Reconstruction and Architectural Guide (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Rodolfo Lanciani, Forma Urbis Rome reprint ed. (Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 1990).

Samuel Ball Platner and Thomas Ashby, A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1929). Preface

Ronald T. Ridley, The Pope’s Archaeologist: the Life and Times of Carlo Fea (Rome: Quasar, 2000).

Luke Roman, “Martial and the City of Rome,” Journal of Roman Studies 100 (2010), pp. 88-117.

Stanford Digital Forma Urbis Romae Project Stanford Digital Forma Urbis Romae Project