Reims Cathedral (Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Reims), begun 1211, Reims, France

Reims Cathedral and World War I

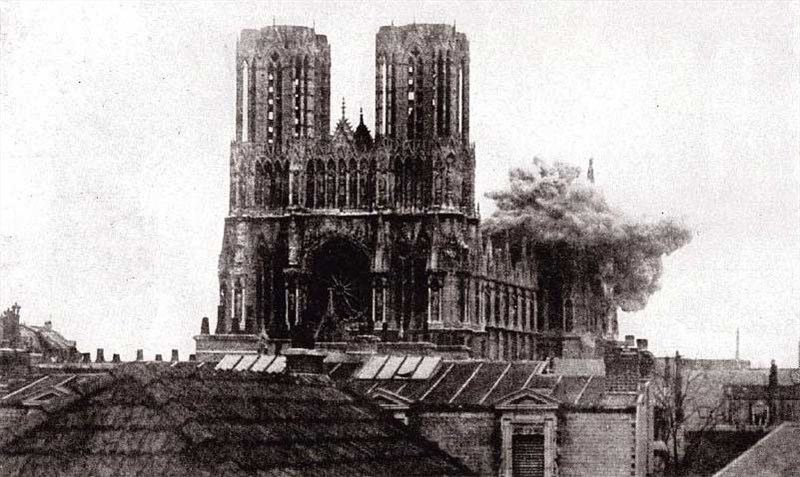

Shell bursting on the cathedral at Reims, from Collier’s New Photographic History of the World’s War, 1918

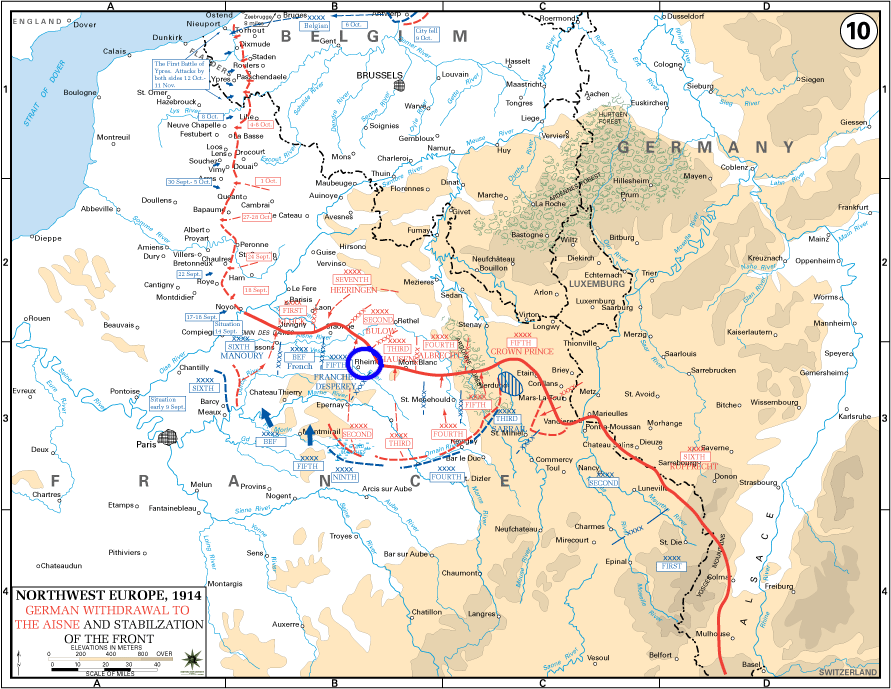

Map of the Western Front, 1914, with Reims circled in blue (map: The History Department of the United States Military Academy, CC0)

The facts…?

World War I officially started July 28, 1914. Originally it was believed that the “situation” would clear itself up by no later than Christmastime. Instead, it took over four long and grueling years, and resulted in more than 15 million deaths. Early on in the conflict, the German army moved into northeastern French territory. This was the beginning of the Western Front. The expeditious land grab by the Germans included the city of Reims. Reims had a well-established history, from its days as a bustling hub of the Roman Empire, to becoming a center of French culture in the early Middle Ages. Additionally, Reims was the “Coronation Capital,” so to speak, the traditional location for the coronation of French kings. It was also home to a magnificent high Gothic cathedral, Notre-Dame de Reims. By early September, the French had forced the Germans to retreat and though the French regained the town, the Germans stayed close by for the entirety of the war.

View of Reims cathedral over the rooftops of the city in 2014 (photo: Dr. Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

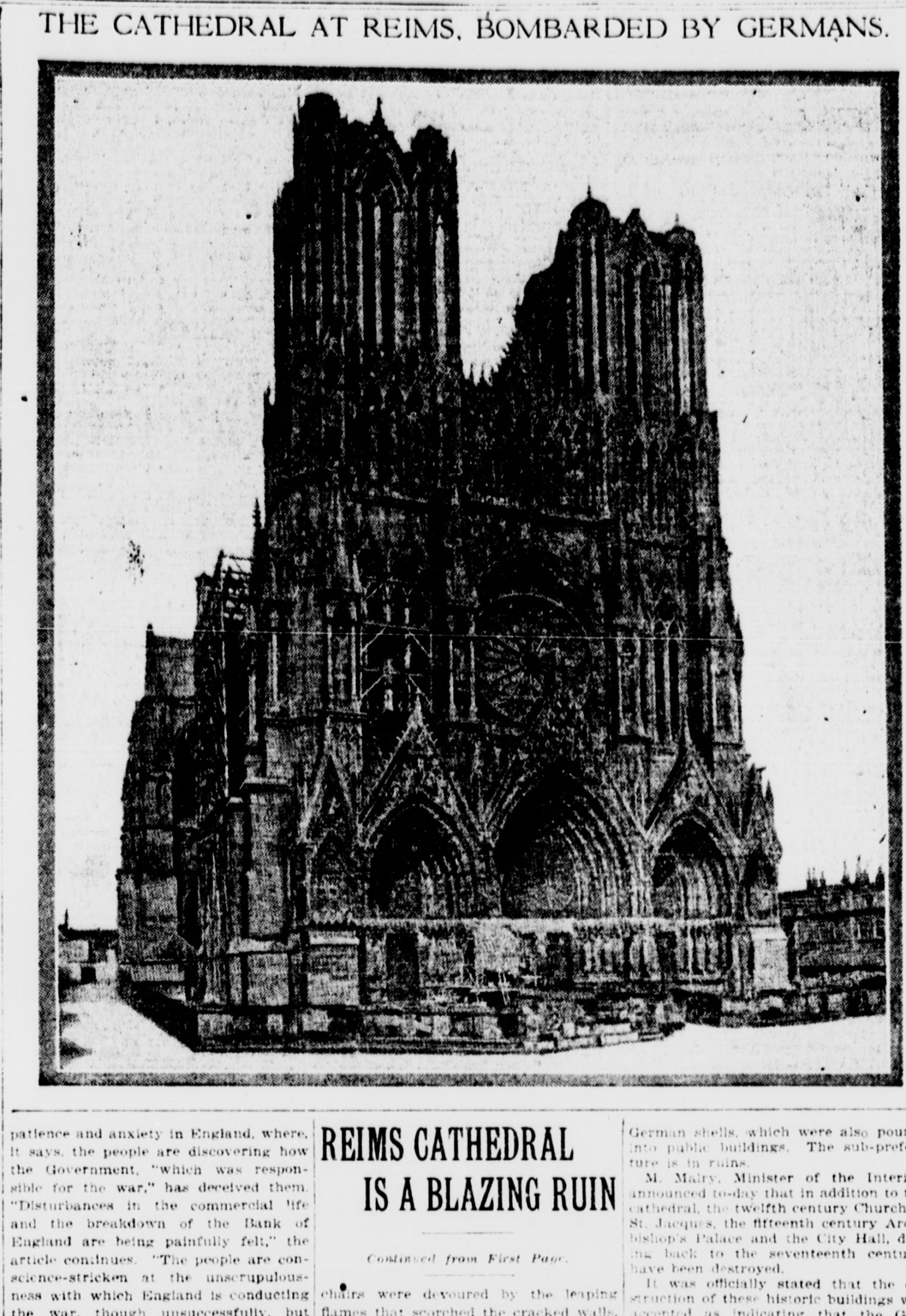

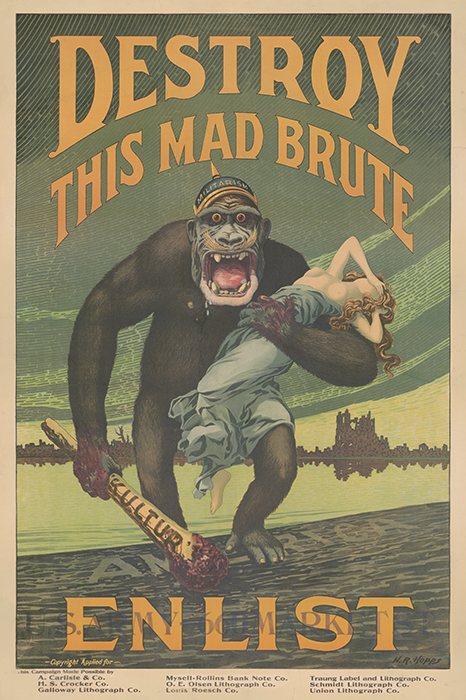

The city of Reims saw significant destruction, and both civilian and military casualties. But no event ignited indignation as did the bombing of the much-venerated Notre-Dame de Reims. The cathedral was first hit by shell fire on September 19th, 1914. Wooden scaffolding that was in place for ongoing repairs caught fire, and contributed to the damage, as did several smaller fires that resulted from the attack. Though the cathedral would be struck again and again as the war continued, it was this initial shelling that sparked a firestorm of outrage, horror, and prodigious propaganda—surely here was damning proof that the Germans were indeed “barbarians,” so lacking in culture themselves that they were compelled to destroy the beauty of another culture out of sheer spite and jealousy. The propaganda insisted that there was no reason to bomb the church since it had no strategic military value, and was a place of sanctuary. The French and their allies stressed that there was no justification to shell the cathedral especially given that was being used to house the wounded (mainly German soldiers callously left behind by their fleeing brothers-in-arms).

“Reims Cathedral is a Blazing Ruin,” The Sun (New York City), September 21, 1914 (Library of Congress)

War crimes

It was acknowledged, even at the time, that the Germans were committing more horrendous acts than the bombardment of Reims Cathedral. So why should a building create more outcry and indignation than the killing of innocent civilians, or other kinds of wartime savagery? Perhaps it was in part that the cathedral, literally meaning the seat of the bishop, could be seen as representing the French nation as a whole, its cruciform shape evoking a sacrificial body. Or, on a more practical note, it was a story that could be easily sensationalized and discussed ad infinitum—cultural war damage was far easier to get past the censors. In the words of Maurice Landrieux, a former priest at Reims but later the Bishop of Dijon “…but it was the most ignoble, because it was at once sacrilegious and stupid, and because it reveals, by its uselessness, the blackest depth of German misdoing.” There was a pervasive belief that the Germans had come to France with the express intention of destroying the cathedral from the outset of the war.

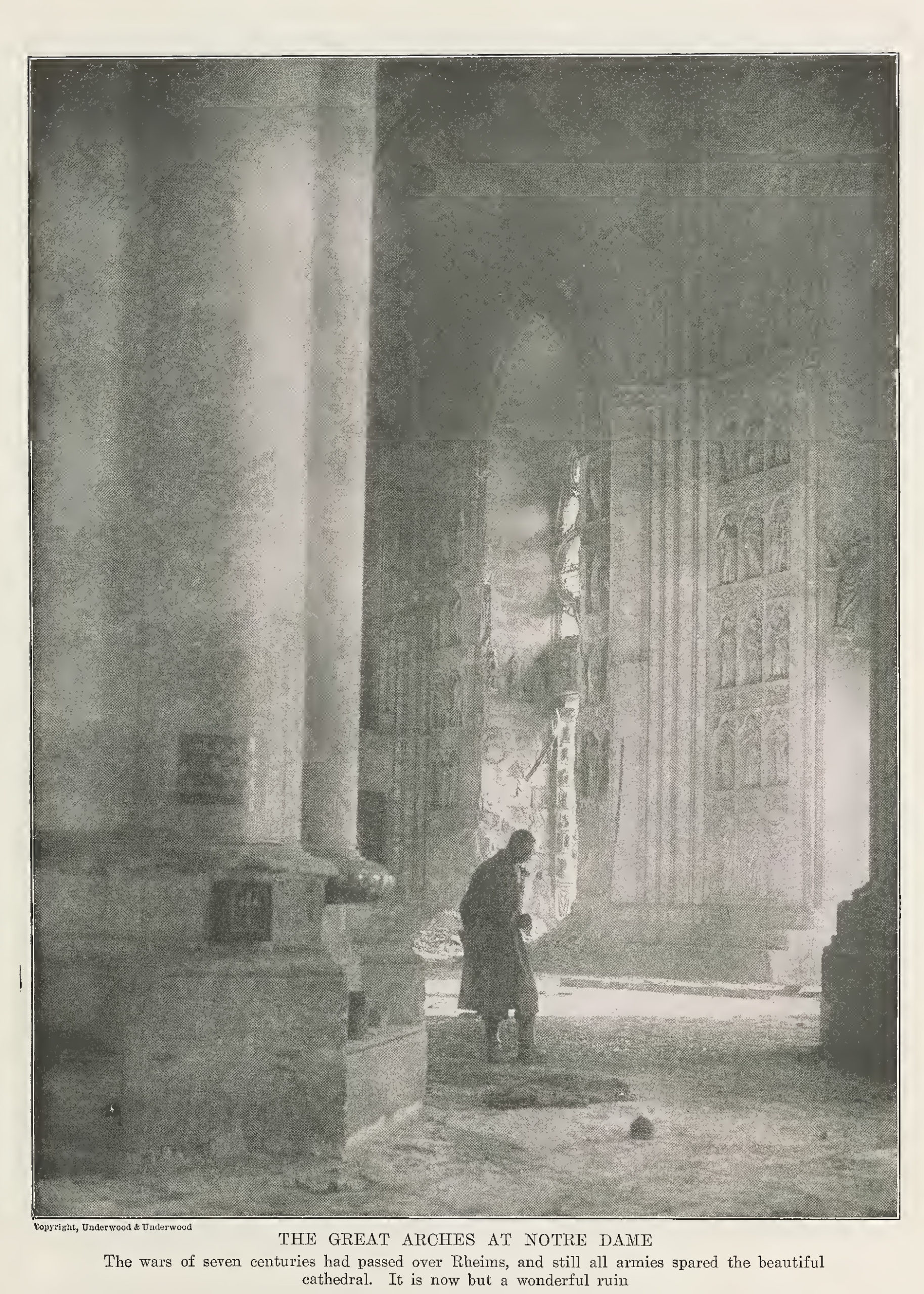

“The great arches at Notre Dame: The wars of seven centuries had passed over Reims, and still all armies spared the beautiful cathedral. Is is now but a wonderful ruin.” from Collier’s Photographic History of the European War, by Francis J. Reynolds and C. W. Taylor, c. 1917

There are two sides to every story, and so it is here. The Germans did shell the cathedral—that is irrefutable. Their explanation as to why they did so was wildly at odds with the French account, and they claimed to be horrified just as deeply as the French, at the damage done to this architectural masterpiece.

The French story was that is that the Germans, before their hasty retreat, had covered the floors of the cathedral with straw, to make it more combustible and that they intentionally left their wounded knowing they would be brought into the church by the French to be tended. A Red Cross flag was raised, a further signal that the cathedral was off-limits as a military target. However, the Germans later claimed the cathedral was being used for military intelligence: a signal station, telephone equipment, and an observation post had been espied in one of the towers during a German fly-by—along with a large cache of weapons. If true, according to international law, the cathedral was a viable military target—a wolf wrapped in sheep’s clothing.

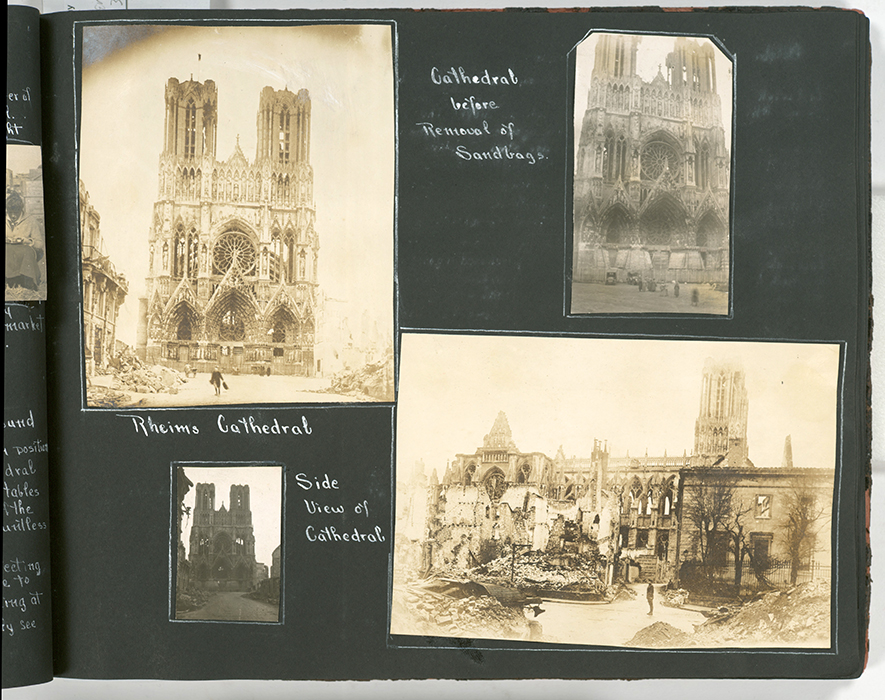

“Cathedral before removal of sandbags (upper right); Reims Cathedral; side view of cathedral” (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

The church was severely damaged—roofs had burned, statues melted, stonework was no longer viable, and more. Nonetheless, the structure was still essentially in good condition after the attack, all things considered. The local French authorities were actually taken to task by their own administrators for not doing a better job putting out the fire, which caused the majority of the damage. The Germans claimed it pained them to commit such an act, but the cunning French had left them no choice. These claims gained little traction.

The result was that—for the French—the German reputation for philosophical thought and general erudition, were suddenly erased—they were viewed once again as one of the “barbarian hordes” of the migration era. German art historians were quick to point out they had been one of the primogenitors of that discipline, and they highly appreciated art from around the globe. German art historians and professors were even dispatched to the front, joining various army units to help provide protection to valuable art on both sides, but to no avail. The mud would not unstick.

Harry R. Hopps, Destroy this mad brute Enlist – U.S. Army, 1918, color lithograph, 106 x 71 cm (Library of Congress)

Culture wars

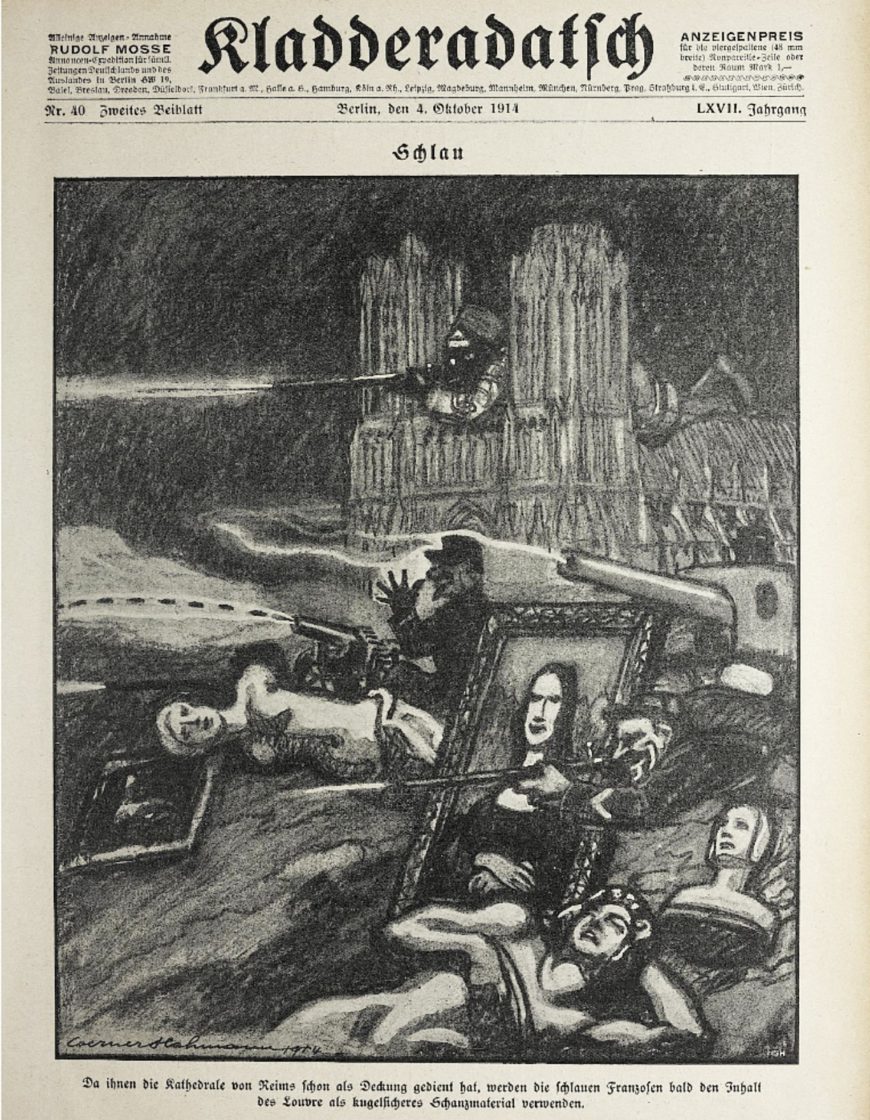

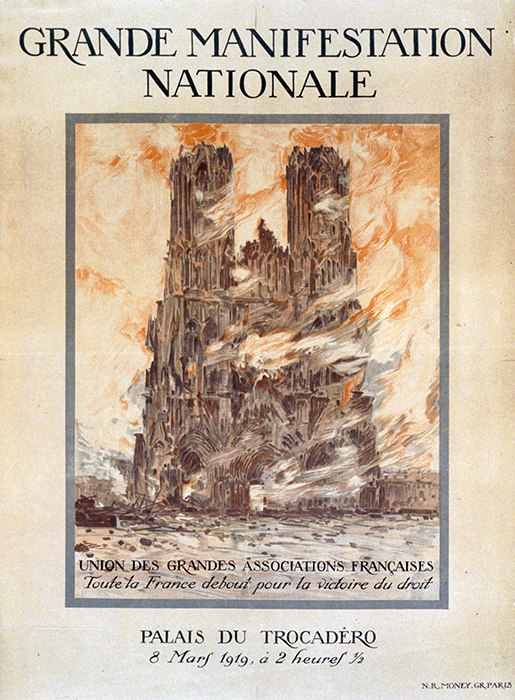

Reims Cathedral continued to be used as propaganda for the whole of the war. Its burnt image was printed on posters and postcards. German soldiers were depicted gun-wielding and slavering at the jaw to seeking to destroy the next great work of art they saw. Meanwhile, the Germans lampooned the French, accusing them of using their own great works of art for nefarious ends without compunction. One well-known cartoon read, “The cunning French have used Reims cathedral as a shooting platform—next they’ll be building trenches with the contents of the Louvre.”

“The cunning French have used Reims cathedral as a shooting platform—next they’ll be building trenches with the contents of the Louvre,” Werner Hahmann, Schlau (Sly), from Kladderarsch, no. 40 (cover, October 1914)

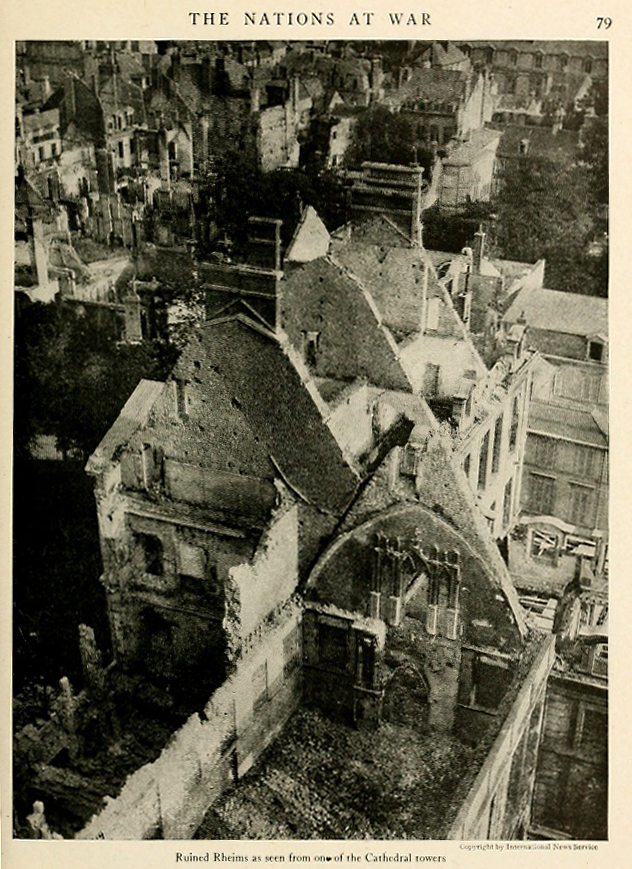

Beyond the trenches, the battle for cultural superiority was on. The French had the upper hand when it came to the events at Reims that fateful night. They could claim eyewitnesses, and they also photographed the cathedral in ways intended to most incite a viewer.

“Ruined Reims as seen from one of the Cathedral towers,” from The Nations at War by Willis John Abbot, 1917

The Germans did try hard though, despite their lack of handy visual evidence, to underscore that they had been the only country to carry out any form of art protection. Kunstschutz (the German term for the principle of preserving cultural heritage and artworks during armed conflict) was said to protect art on both sides of the war. It was even said to be endorsed by Kaiser Wilhelm II himself. The Germans emphasized that the bombing of the cathedral at Reims had not been part of a systematic effort, instead, it was one of the many sad byproducts of the war.

E. Lemielle, Souvenez-vous! 1914. Rien d’Allemand!!! Des Allemands (Remember! 1914. Nothing German! Nothing from the Germans), 1919, color lithograph, 83 x 60 cm (Library of Congress)

Neither side held back, each was determined to show that while one was on the side of the angels, the other was ruthlessly attempting to profit by the destruction of art. Meanwhile, the Germans claimed that as they were the creators of the Gothic style, and so the cathedral was just as much part of their cultural heritage as it was France’s, and they again attempted to remind the world of their integral role in the creation of art history. Again, this gained no traction with the French, nor with most nations.

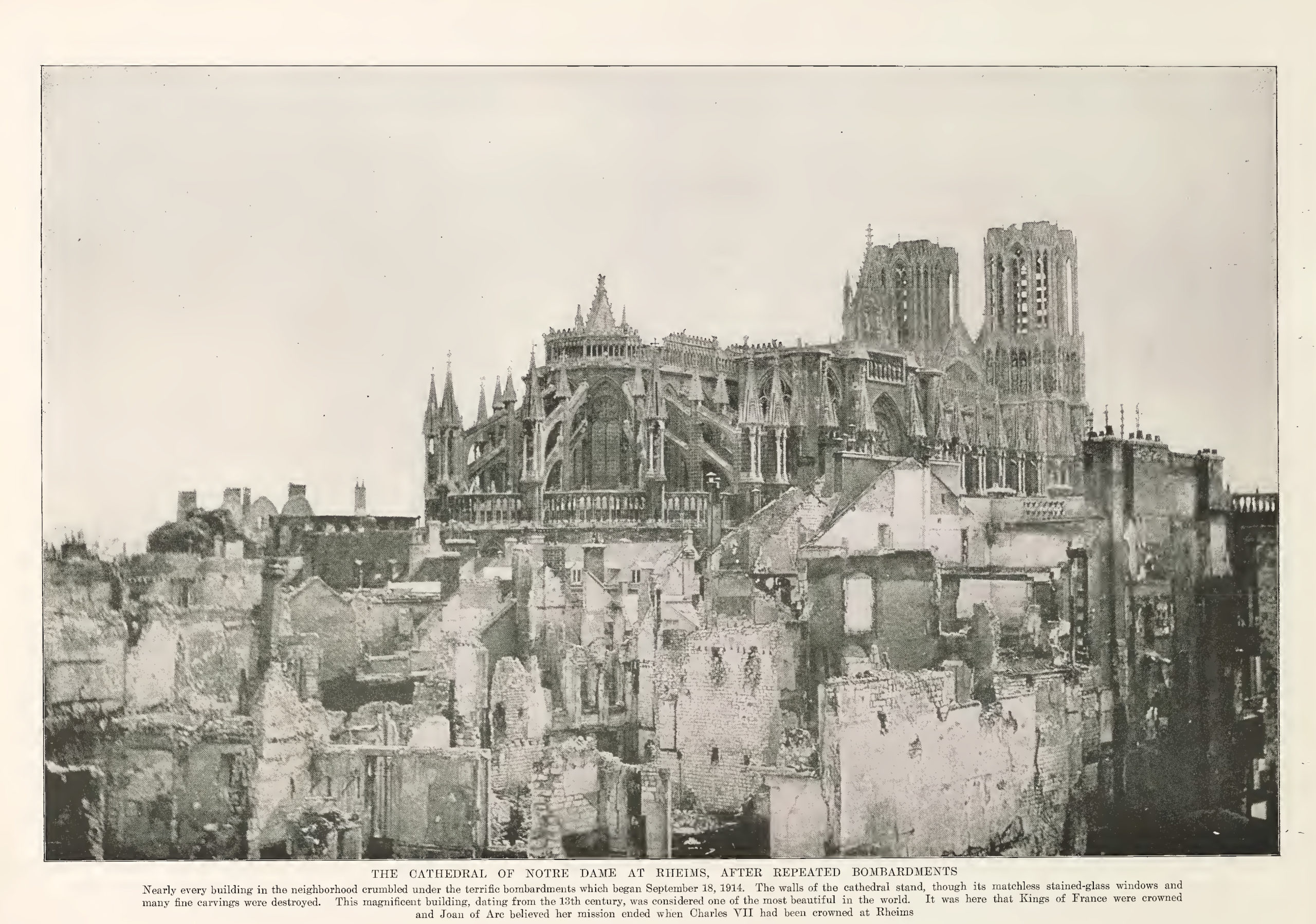

“The cathedral of Notre Dame at Reims, after repeated bombardments,” from Collier’s Photographic History of the European War, by Francis J. Reynolds and C. W. Taylor (c. 1917)

By the end of the war Reims, which had been targeted multiple times, was the ruin the French had claimed after the initial attack. The continued attacks on the cathedral called into doubt the veracity of the Germans’ initial account. After the first bombardment, it was certain that the cathedral was no longer being used for any military purpose—if it ever had been. Again, a cultural landmark of this kind could only become subject to brute force with good reason, so the continued bombing only furthered the French position of German brutality and outright vandalism. J.W. Garner, in his International Law and the World War, states, “Monuments of this stature are not only entitled to respect because of their sanctity but are especially protected because of the Law of Nations” (p. 445).

Grande Manifestation Nationale, 1919, color lithograph, 80 x 59 cm (Library of Congress)

Restoration on the cathedral began almost immediately after the end of the war, funded in part by the Rockefeller family. The cathedral reopened in 1938, though work continues to this day. Recently, the world looked on aghast when, in April of 2019, the iconic Notre-Dame de Paris burned. Even more recently, the lesser-known Cathedral of Saint Peter and Saint Paul in Nantes, another Gothic jewel, caught on fire. In these cases there appears to be no terrorism involved, only age and human error. Perhaps then, the most important take-away from the bombing of Reims Cathedral is that blame is, to a degree, irrelevant, at least after the fact. The real lesson is that we must do better at preserving our cultural heritage the world over.

Marc Chagall, stained glass windows replacing war-damaged ones, Reims Cathedral, 1967-1985 (photo: Dr. Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re in the square in the city of Reims, in France, looking at one of the great Gothic cathedrals.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:12] Everything seems to reach heavenward.

Dr. Zucker: [0:14] It’s pierced everywhere.

Dr. Harris: [0:16] As we look at it, it hardly feels like stone. It has a weightlessness.

Dr. Zucker: [0:21] This is a characteristic of the High Gothic period.

Dr. Harris: [0:24] We’re not far from Paris. In fact, the great Gothic and High Gothic churches form a circle around Paris.

Dr. Zucker: [0:33] This period in the 12th and 13th centuries was a period when France was not the nation as we now know it. The Capetian monarchy, the king of France, was in control only of the Île-de-France, the area that surrounds Paris. Beyond that, other feudal barons, lords, controlled large areas.

Dr. Harris: [0:50] It’s during exactly this Gothic period that the Capetian monarchs expand their territory and increase their power. One of the ways that they do that is by cathedral building.

Dr. Zucker: [1:02] A building like this doesn’t spring out of nothing. This is based on centuries of experimentation that we can see especially in great Romanesque churches in the years after the turn of the millenni[um].

Dr. Harris: [1:13] The desire to build roofing out of stone that we see beginning in the Romanesque reaches a perfection during the Gothic. It’s these developments in things like flying buttresses and in the groin vault that allow the Gothic builder to build so tall, so high, to pierce the walls in the way that he does to allow light to enter the building.

Dr. Zucker: [1:37] All of that is in the service of the spiritual, to use light symbolically to create a space that is meant to represent heaven on earth.

Dr. Harris: [1:45] Typically, for both Romanesque and Gothic churches, we have a west front, which has three entrances. Generally, that reflects the interior of the church.

Dr. Zucker: [1:55] These are called portals. They reflect the interior because the central doors enter into the widest part of the building, the nave, and each of the side doors open up into the side aisles.

Dr. Harris: [2:05] Beginning in the Romanesque period, we begin to see figures on either side of the doorway and above the doorway in a space called the tympanum. The figures on either side are called jamb figures.

Dr. Zucker: [2:16] Because they’re attached to the door jambs. Then, surrounding the tympana, almost like amplification of the shape, are archivolts. These radiate out, and here, they create enclosed porches.

Dr. Harris: [2:28] They’re quite deep. They create this funnel that draws the visitor in. Now, here at Reims, instead of sculpture, we have stained glass in the tympana. The sculpture that we would expect to see in the tympanum is now above that in the gabled spaces above the archivolts.

Dr. Zucker: [2:46] Just above the rose window in the central portal, there’s another, even larger rose.

Dr. Harris: [2:52] At this cathedral in particular, the artists have achieved amazing things with the stained-glass windows. They’ve reduced that stone that holds the glass in place to very fine tracery. It seems miraculous that that glass is being held in place.

Dr. Zucker: [3:09] Glass has even been added around the rose itself. Solid stone in earlier churches has here been opened up to allow even more light in. On either side of the rose window are two enormous towers, pierced throughout so that light pours through them, and they seem delicate.

Dr. Harris: [3:26] Then we have another feature which is typical of Gothic churches. In this case, it’s located above the rose window. This is called the Gallery of Kings. Here, we have a row of Old Testament kings, who are understood as the ancestors of Christ. According to the New Testament, Christ traced his lineage back to the house of King David.

Dr. Zucker: [3:48] This is called the Tree of Jesse. That refers back to Jesse, the father of King David. In this particular church, at the center of the Gallery of Kings, we see the baptism of King Clovis, the man who begins the ancient Merovingian dynasty, a dynasty that the more modern kings of France would have looked back to.

Dr. Harris: [4:06] What happened at Clovis’ baptism was a miracle. The oil required to anoint him during the coronation ceremony was miraculously received by the bishop from a dove sent by God.

Dr. Zucker: [4:20] That legend is important because this is the cathedral where the coronation ceremonies took place, where the kings of France received their divine inspiration, their divine power.

Dr. Harris: [4:30] Let’s go take a closer look at the central doorway. What strikes me most of all as we approach any of these three doorways is how animated the jamb figures are. They tilt their heads. They move their bodies. Many of them look down at us.

[4:46] It feels as if they’re alive. If we imagine that they were once painted, that would have enhanced their realism to any visitor walking through these portals.

Dr. Zucker: [4:56] If they were real, they were giants. These are large sculptures.

Dr. Harris: [5:00] Significantly larger than life size.

Dr. Zucker: [5:03] We’ve walked into the central portal. We’re looking at the jamb figures that are on the right side. We have two scenes. On the left is the Annunciation. We see the angel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary. The Annunciation is the moment when the Archangel Gabriel visits Mary with the news that she will bear Christ.

Dr. Harris: [5:20] On the right, we see a scene known as the Visitation, when Mary’s cousin Elizabeth visits. They’re both pregnant. Elizabeth is pregnant with Saint John the Baptist, and of course Mary is pregnant with the Christ Child.

Dr. Zucker: [5:34] When you look at these two pairs of sculptures, you can see that they were carved at different times and in very different styles.

Dr. Harris: [5:41] This is a big undertaking, to build a cathedral. Not only would you have to have many masons who are cutting and carving stone, but also many sculptors who were working, likely coming from different workshops in the region.

[5:55] It makes sense that you might have sculptures that are stylistically different. Here at Reims especially, we know that sculptures were moved from different locations on the building, and so it’s not quite as coherent as we might see at another Gothic church, like Amiens, for example.

Dr. Zucker: [6:13] Look at the figures on the right. They look so classical. They’re wearing drapery that at first glance seems as if it could come from ancient Rome.

Dr. Harris: [6:21] Right. That’s what we mean by classical, looking back to the cultures of ancient Greece and ancient Rome, and we know that Reims was an important ancient Roman city. There are ancient Roman ruins here that may have been an important source of inspiration for the sculptors who did this scene of the Visitation.

Dr. Zucker: [6:39] So much so that earlier art historians thought for a time that these might actually be antique sculptures from ancient Rome.

Dr. Harris: [6:45] What makes them look so classical, so ancient Greek or Roman, is that clinging drapery. We could think back to the sculptures on the Parthenon, for example.

Dr. Zucker: [6:56] Like those ancient Greek sculptures, we see attention to the bodies below the drapery. When we look at Mary, we see her right knee projecting out, a traditional way of representing the body that we call contrapposto, where her weight is largely on her left leg in this case.

Dr. Harris: [7:11] However, one of the tips that tells us this is not classical, but is in fact Gothic, is that that sway in her hip that forms an S-curve in her body, is exaggerated. That’s something we do see quite often in High Gothic sculpture.

Dr. Zucker: [7:26] This is a characteristic that was considered quite elegant and part of the courtly culture, especially of 12th and 13th century France.

Dr. Harris: [7:34] In early Gothic sculpture, when we had jamb figures, there was a very close association between the figures and the columns behind them. Here, the figures seem to almost have nothing to do with the columns behind them. They’re very independent.

[7:49] The figures interact with one another. There’s a sense of freedom from the architecture so that we almost read these as freestanding sculptures.

Dr. Zucker: [7:59] Let’s take a look at the Annunciation. It’s not just that this pair contrasts with the classicism of the Visitation, but the figures are different from each other.

Dr. Harris: [8:07] We seem to have actually these two pairs of sculptures, the hands of three different sculptors.

[8:13] Compared to the figures around her, Mary seems very simple. She might hark back to an earlier Gothic style. Her drapery is primarily these lines that fall straight down toward her feet. We have very little sense of a body underneath that drapery.

Dr. Zucker: [8:30] She reminds us of the more columnar figures at Chartres. Although she has more mass, she has more solidity. She’s more of this world.

Dr. Harris: [8:39] Look at how kindly her face appears — gentle, generous. Mary is understood as an intercessor, someone who intercedes between human beings and the divine, as someone who can appeal to Christ and help ensure our place in heaven.

Dr. Zucker: [8:56] That is beautifully represented by the angel to her left. This is Gabriel, announcing to Mary that she will bear Christ. In this case, the angel is represented with anatomy that seems otherworldly. The head is quite small, the body is lyrical. The carving is incredibly delicate, and Mary seems earthly in comparison.

Dr. Harris: [9:16] He is very elongated, a very thin, graceful neck. The way he pulls up his drapery seems like a very refined member of the court in Paris. Art historians believe this is the latest of these four figures.

Dr. Zucker: [9:33] The original paint, the original polychrome, is still visible. This is a reminder that all of these figures would have been brightly painted.

Dr. Harris: [9:41] That lovely angelic smile, that otherworldly smile, the puffing of the skin around the eyes, the delicate curls of the hair, these are features that we see in other sculptures from this time period.

Dr. Zucker: [9:56] And that we can see in other jamb figures on this church. If we turn around to the left side of the central portal, we see especially the figure known as Joseph carved in style that is very similar to the angel.

Dr. Harris: [10:08] Last but not least, we have a figure in the center as we look toward the doorway. This is called the trumeau, which supports the lintel. Here we see a very typically Gothic sculpture of Mary holding the Christ Child, supporting him on her hip with that sway of drapery.

Dr. Zucker: [10:27] As a reminder that this church was closely associated with the Capetian monarchy, she wears a large crown. There is this immediate association between temporal and divine power.

Dr. Harris: [10:39] As we stand in this doorway, about to walk into the church, I’m reminded of the medieval visitors who would have looked up and seen figures that they were familiar with. They would have heard sermons about these figures. They would have heard chants and songs. In many ways, these figures were alive for them as we enter the church.

Dr. Zucker: [11:00] We’ve entered into the cathedral. We’ve walked past the nave to the side aisle, and we’re looking now across at the interior elevation.

Dr. Harris: [11:08] This is a very typical elevation for a Gothic cathedral. We have the nave arcade, the row of arches that we see on either side of the nave, and we notice that they’re pointed, which is a very typical feature of Gothic architecture. Above that, we see a triforium.

Dr. Zucker: [11:27] Now, above that is the clerestory, these soaring windows. In this case, two very tall lancet windows, and above the lancets, a small lobed window that looks like a small rose.

Dr. Harris: [11:40] Sometimes called an oculus. Here, even in the spaces between the lancets, even there, we have glass, so this idea of opening up as much of the wall as possible to the glass. Now, that’s a really difficult feat when you have a stone vaulted ceiling.

Dr. Zucker: [11:58] Which weighs a tremendous amount, and which exerts tremendous pressure downward and out. All of that needs to be supported.

[12:05] Part of the brilliance of the Gothic is the understanding that that weight can be borne, not entirely inside the church with massive piers, but much of that weight can be drawn outside and supported by flying buttresses that allow for light to come into the church unobstructed.

Dr. Harris: [12:23] If we go back to the Romanesque, those stone vaulted ceilings were carried by these massive, heavy walls. Along with the flying buttress that allows Gothic architects to open up the walls to allow for this light is the use of the ribbed groin vault.

Dr. Zucker: [12:41] Let’s start at the bottom. We have large piers, visually made lighter by the addition of these engaged columns, what are called colonnettes, that rise delicately up and that continue the entire length of the elevation, all the way up to the center of the vaulting.

[12:57] A groin vault is the intersection of two barrel vaults. The Romanesque was in love with the idea of taking the Roman arch and extending it in space to create a barrel vault. But what happens when you intersect, at 90 degrees, two barrel vaults? You get a curved X shape that’s known as a groin vault.

Dr. Harris: [13:15] One of the benefits of the groin vault is that it allows the weight to come down onto points instead of continuous walls. That allows one to open up the space.

Dr. Zucker: [13:27] In this case, the vaulting is four-part, and at the intersection of those four parts, we have ribbing. That was an important architectural innovation that allows for much of the work of holding up the building to be taken by that ribbing rather than the webbing in between. Gothic architects often used a type of stone that was lighter for that in-between space.

Dr. Harris: [13:50] As we look down the aisle at the ribbing, we see this lovely pattern, creating linear decoration.

Dr. Zucker: [13:58] The linear is seen everywhere in the interior. But we also have it interrupted by beautiful decorative passages that are foliate, that is, that show foliage, leaves. We see it at the top of columns. We also see it separating some of the sculpture on the interior west wall.

[14:14] The fact that architecture is purposefully using light as a symbolic expression of the divine is quite extraordinary. Light can pass through glass. It is a magical substance. Here, architects are weaving it into the very fabric of the building.

Dr. Harris: [14:30] To give us a sense of the heavenly. One of the things that distinguishes this cathedral from others from this period is that we’re missing so much of the original stained glass.

[14:42] This city was heavily bombed during World War I, and the cathedral sustained real damage that took decades to rebuild.

Dr. Zucker: [14:51] That’s most evident in the destruction of some of the sculpture on the exterior of the building, but also in the loss of the original glass in the clerestory in the nave.

[14:59] What the destruction of World War I afforded the church was the opportunity, though, for modern artists — most notably Marc Chagall — to create new windows for the church. We see a set of gorgeous lancet windows in the axial chapel, the back-most chapel in the church.

Dr. Harris: [15:16] We’ve walked back down toward the west end, toward the entrance, and we’re immediately faced by this unusual and fabulously beautiful sculpted wall. We’re looking at dozens of figures in small niches that surround the rose window.

Dr. Zucker: [15:33] This screen frames each of the three portals. It’s interesting to note that the subjects that are represented on the interior west front reflect the subjects on the exterior portals.

Dr. Harris: [15:43] One can imagine the king, after the coronation ceremony, after the king is imbued with divine power, turning around to process out of this doorway and looking at the very scenes we’re looking at today.

Dr. Zucker: [15:59] Two of the most prominent niches, just to the right of the main portal, reflect the relationship between the church and the king. We have the two Old Testament figures, Melchizedek and Abraham.

Dr. Harris: [16:10] Both are dressed in the garb of the Middle Ages. We might not immediately recognize Abraham because he’s dressed as a knight.

Dr. Zucker: [16:19] Although both Melchizedek and Abraham were kings, here, in his knightly garb, Abraham represents the monarchy.

Dr. Harris: [16:26] To his left, Melchizedek from the Old Testament, who is both a king and a priest. He’s administering bread and wine to Abraham.

Dr. Zucker: [16:37] It’s a reminder that in the 12th and 13th centuries, in fact, for the entire medieval period, there is a complex relationship between the church and the king, between spiritual and temporal power.

Dr. Harris: [16:48] You have a king coming here to be anointed, to be crowned as king.

Dr. Zucker: [16:54] By the church.

Dr. Harris: [16:55] By the archbishop. There’s that sense in which the archbishop is empowering the king. On the other hand, the king, once he’s anointed during the coronation ceremony, becomes God’s vehicle on Earth to protect and care for his kingdom.

[17:13] You do have this almost co-equal powers during the Middle Ages, here exemplified by the pair of figures of Melchizedek and Abraham.

Dr. Zucker: [17:22] Melchizedek reaches towards Abraham. Abraham, his hands together in prayer, bends forward towards Melchizedek. It’s almost as if the architectural frame that surrounds each disappears.

Dr. Harris: [17:33] Yet we’re drawn to that beautiful foliage pattern that surrounds each of these niches, a reminder of how important the natural world was becoming during the Gothic period. This is a time of renewed interest in the philosophy of Aristotle, but also a renewed interest in nature.

Dr. Zucker: [17:52] Make no mistake, this is not the Renaissance, but there are focused moments of naturalism in medieval sculpture, and we see that here in the representation of the oak, of some of the vines, as a framing motif.

Dr. Harris: [18:03] All of this in the service of understanding the world, the universe that God created for us, and the vehicle of the church for our salvation.

Dr. Zucker: [18:13] The church is still breathtaking. One can only imagine how miraculous it must have seemed to somebody in the 13th century.

[18:19] [music]