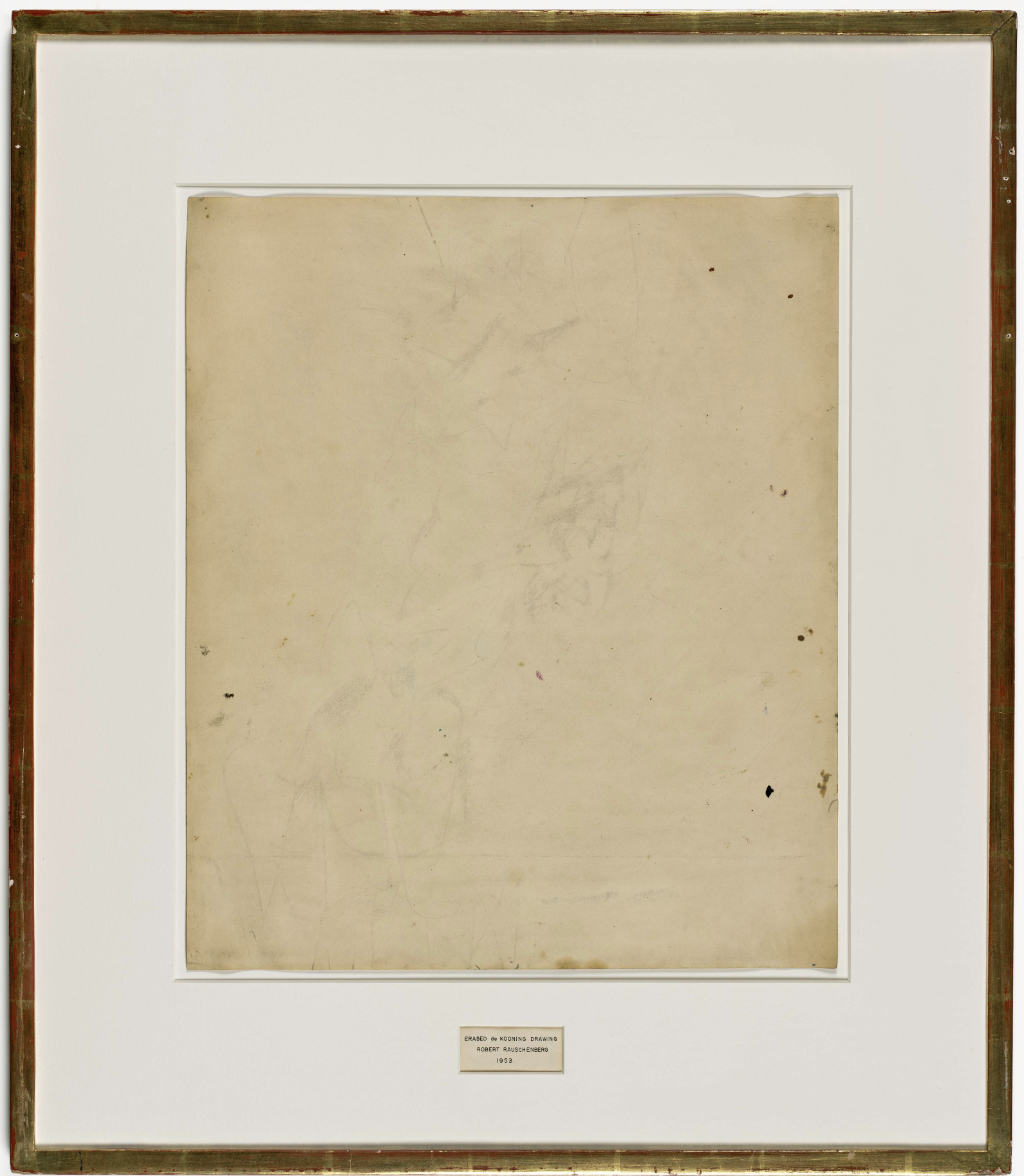

Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953, traces of drawing media on paper with label and gilded frame, 64.14 cm x 55.25 cm (© Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, SFMOMA)

That’s right, the Erased de Kooning Drawing is… an erased drawing by Willem de Kooning. It is also a statement that the “erasing” artist, Robert Rauschenberg, made about the artistic culture of his time and about his own artistic practice.

Community meeting, Black Mountain College (photo: Black Mountain College Museum)

How It Happened

In the Fall of 1952, the young artist Robert Rauschenberg visited the New York studio of Willem de Kooning. Rauschenberg met de Kooning and befriended him as a student at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. By 1952, de Kooning was a leading figure, along with Jackson Pollock, in Abstract Expressionism, one of the first modernist art movements in post-World-War II New York. Both de Kooning and Pollock had forged a radically new style of abstract painting, and de Kooning would become particularly well known for a painting series that dramatically distorted the female form. The so-named “de Kooning style,” in fact, became a template for modernist painting for years to come.

Rauschenberg with Jasper Johns, John Cage, and others in Rauschenberg’s or Johns’s Pearl Street studio, New York, c.1955 (photo: Jerry Schatzberg)

But Rauschenberg was not interested in painting like de Kooning; his plan, as he told the elder artist, was to erase one of his drawings. And de Kooning agreed, after having chosen one that might prove difficult to undo, as it had been done in charcoal, oil paint, pencil, and crayon. Rauschenberg dutifully erased it over the ensuing weeks.

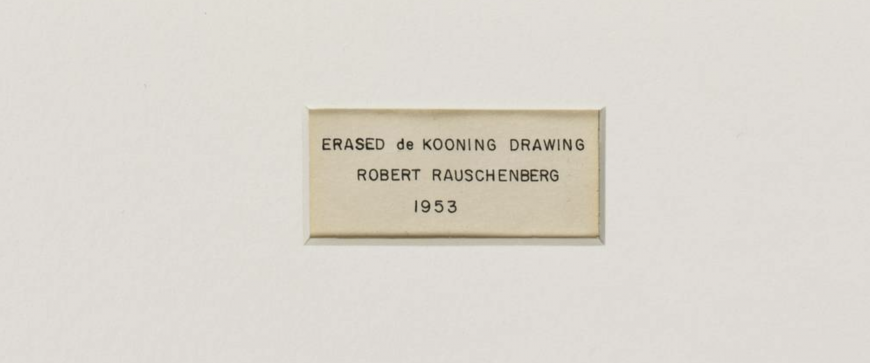

Fellow artist and Rauschenberg’s longtime friend, Jasper Johns would later provide a gilded frame and mat, onto which was placed an inscription for the re-titled drawing: “Erased de Kooning Drawing, Robert Rauschenberg, 1953.”

Cultural Context of Abstract Expressionism

Rauschenberg’s erasure was at odds with the prevailing sensibility in art during the 1950s in America. Abstraction had emerged as the defining characteristic of Modernism. In fact, it became a kind of post-war call-to-arms, vigorously promoted by the influential art critic Clement Greenberg. Accordingly, all art, whether it be painting, sculpture, or photography, was to pursue a path that eliminated subject matter and narrative, whilst focusing instead upon the expressive qualities of the medium. This often took the form of highly gestural and non-representational mark-making. Since it was painting that best embodied this new approach, it was painting that reigned as the dominant artistic medium of the Post-World-War II years.

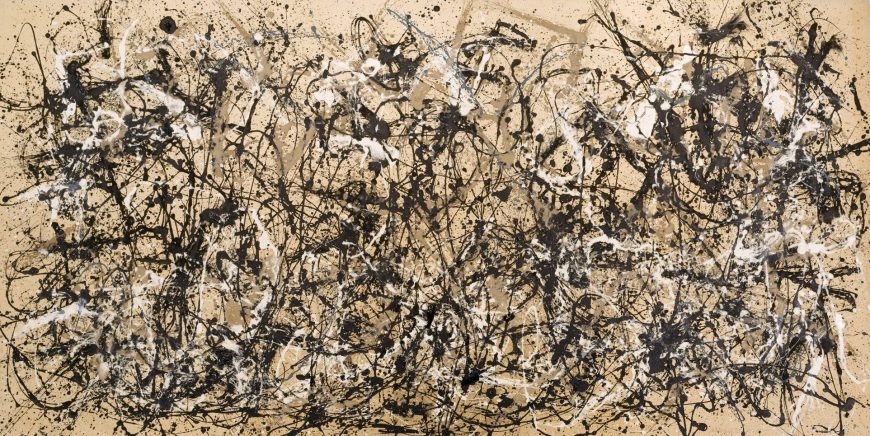

Jackson Pollock, Autumn Rhythm (Number 30), 1950, enamel on canvas, 266.7 x 525.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Whether it was the overall effect of Jackson Pollock’s so-called “drip” paintings (in which paint had been flung or dripped across large canvases), or the stained pools of color in the work of Helen Frankenthaler, or even the distorted images in de Kooning’s Women series, the unifying force was a will to abstraction. Pollock once famously remarked that if what he was painting veered too closely to resemblance, he would paint it out.

Even photography tried to mimic painting’s abstract qualities. The documentary photographer Aaron Siskind had created portraits of rural America in the 1930s, but by the 1950s his photographs were reduced to black and white arrangements of form. Abstraction was seen by many artists as a liberating force, especially in the context of American realist painting of the preceding decades. Folkish American subjects and themes now seemed provincial compared to what had been achieved in Europe and particularly France since the early twentieth century.

Most significantly, abstraction embodied a specifically postwar American sense of individualism. Through the gestural and often theatrical or performative act of making marks upon the large, flat expanse of canvas, the artist was freed from the constraints of subject matter. In Abstract Expressionist painting, the subject matter, if there can be said to be one, was the artist himself. I use the gendered pronoun “himself” purposively here since it was male artists who were the celebrated authors of these muscular paintings, requiring large brushes and massive canvases. This is not to say that women did not produce powerful bodies of work in this period—indeed Lee Krasner, Janet Sobel, Buffie Johnson, Anne Ryan, Hedda Sterne, and others did just that.

Lee Krasner, Untitled, 1953, oil paint, gouache and paper, 57 x 76.2 cm (National Gallery of Australia © estate of Lee Krasner)

Erasing conformism: Rauschenberg’s Neo-Dada

One of the Black Mountain Poets, Robert Duncan described the “bravura brushstroke” as evidence of “the power and movement of the arm itself” and of the “involvement of the painter in the act.” [1] It is hard not to see in this statement evidence of the gender bias that reflected a prevalent idea according to which painting powerfully on large surfaces meant painting like a man.

In this regard, it is important to point out that Rauschenberg was gay, and like women and even artists of color, invariably deemed too far outside the extremely conformist culture of 1950s America to produce the requisite kind of art that was needed to prove America’s place on the international stage. Metaphorically therefore, it could be argued that Rauschenberg was erasing not just a drawing, but this very idea of artistic, masculine authorship.

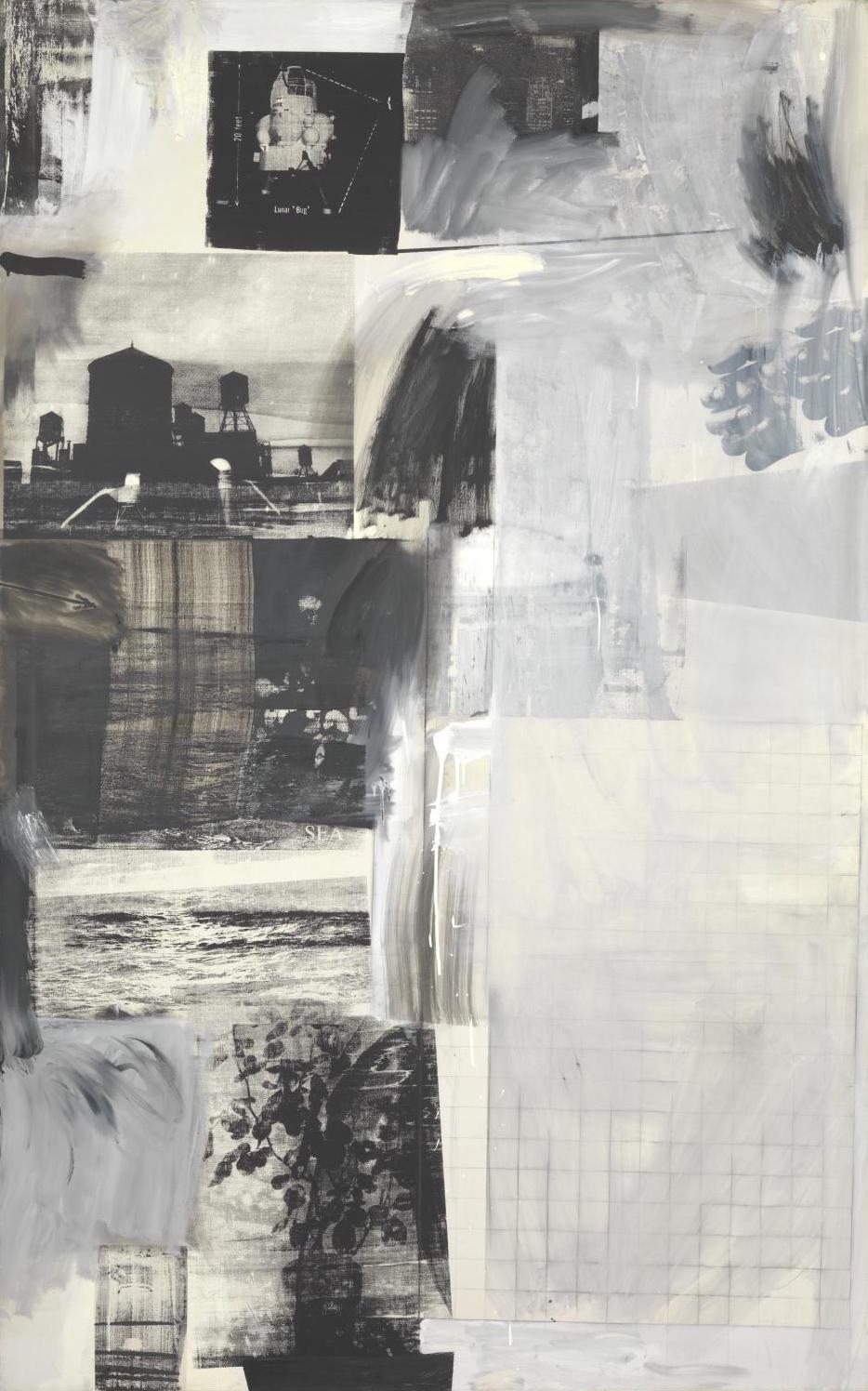

Example of Neo-Dada work by Robert Rauschenberg, Almanac, 1962, showing the artist’s continuous use of erasure as a formal and conceptual tool (© Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, image: Tate)

Erased de Kooning Drawing thus had symbolic force. Though, as one can imagine, that force was mostly viewed by critics as negative. Rauschenberg’s erasure was a destructive act, to be sure, one that seemed to harken back to a World-War-I movement called Dada, in which traditional ideas of art were challenged in often absurd ways. Rauschenberg’s seeming nihilism would, in the later 1950s, be called “Neo-Dada,” and he would be linked to Marcel Duchamp whose anti-art objects had resurfaced in New York during the 1950s. But Rauschenberg saw the erased drawing in very different terms and possibly as a follow up to a series of white paintings in which canvases were entirely painted white.

“It was nothing destructive…. I was trying to purge myself of my teaching…so I was doing monochrome no-image.”Robert Rauschenberg in conversation with Tanya Grosman, Interview, vol. VI, no. 5, 1976

Of course we must always weigh the proclamations of artists against the cultural climate in which they work. Rauschenberg’s coy statement would not mark the first time an artist feigned indifference or ignorance of the larger meanings of their work. American artists had finally achieved what they believed to be a truly modern art that could rival Paris. It was also no coincidence that America had emerged as a superpower in the world at large. There was, as a result, a heroic sense about the whole affair; artists inadvertently became cultural cold warriors. Rauschenberg seemed cavalier about it all. In the words of one critic: “We have finally won, are we going to throw it all away?” [2]

Label (detail), Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953, traces of drawing media on paper with label and gilded frame, 64.14 cm x 55.25 cm (© Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, SFMOMA)