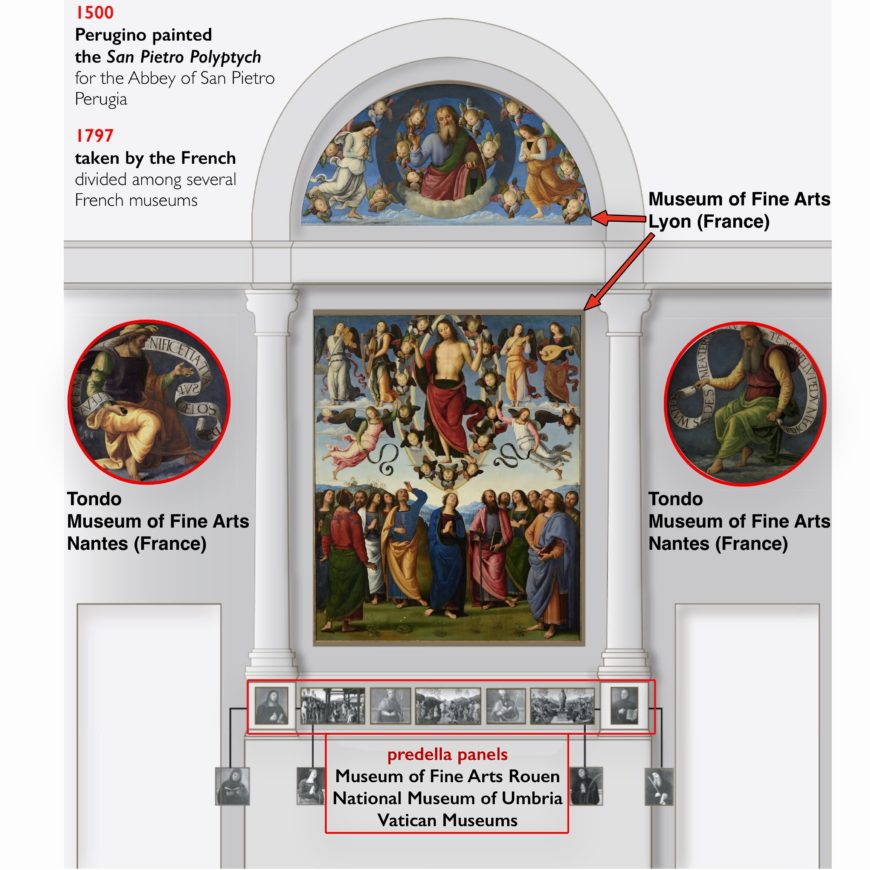

Diagram showing where the different panels were distributed after the altarpiece was confiscated. Perugino, San Pietro Polyptych, for the Abbey of San Pietro, Perugia, 1496–1500.

Millions of people travel to Paris annually for the pleasure of visiting the Louvre Museum. Visitors are awestruck by the grandeur of the galleries and the wealth of the artistic treasures on display. For most museum-goers, the architectural decorations and the carefully curated works of art in the galleries create a unique ambience, one that gives the illusion that these works of art have always lived in these spaces. However, those who are interested in historical instances of looting are quick to point out that the Louvre Museum’s collection contains a treasure-trove of stolen works of art. What is often omitted from modern museum guidebooks is the fact that some works of art in the Louvre’s collection were confiscated locally, during the formative years of the French Revolution (1789-1793). A few years later, the French would begin to appropriate works of art on an international scale. Arguably, some of the most egregious instances of confiscation took place on the Italian peninsula. The Vatican was one of the main victims and its collections, as well as those of papal cities such as Perugia, were specifically targeted.

Art looting at home and abroad

The fascinating historical events that gave birth to the Louvre Museum’s collection began when the French Revolutionary government nationalized the collections of the church, émigrés (who had fled the country), and the monarchy. The French government was then free to decide whether these collections would be sold, destroyed, or kept. A system was developed to select and preserve works of art and other cultural objects from these collections that were considered to be of artistic and cultural significance.

Nationalizing these collections fell short of the revolutionary government’s ambitions however, and shortly after the Louvre Museum opened its doors to visitors in 1793, the government developed a plan to augment the national collection at the Louvre through art confiscations perpetrated abroad. At nearly all its territorial borders, France was facing wars with members of the First Coalition (1793-1797), which included Spain, Holland, Austria, Prussia, Great Britain, and Sardinia. The political reasons behind the establishment of the Coalition are complex, but the cornerstone of their plan was to quell the Revolution and to restore the monarchy (the French King had been executed by the revolutionaries in 1793). Despite the Coalition’s efforts, the French army successfully pushed back their advances. In the territories that the French conquered, they took art, money, and parcels of land as compensation for the resources that were expended in fighting wars that the Coalition had provoked.

Map showing many (but not all) of the cities where the revolutionary forces under Napoleon confiscated art

At first these appropriations of works of art took the form of unorganized looting during the French army’s early military campaigns. It was not until the campaign in Belgium (in 1794) that the French government officially sanctioned art confiscations and a coherent program of appropriation emerged.

This altarpiece by Rubens was taken from a church in Antwerp (just north of Brussels) to the Louvre and returned to Antwerp in 1815 after Napoleon’s defeat. Peter Paul Rubens, Elevation of the Cross, from Saint Walpurgis, 1610, oil on wood, 15 feet 1-7/8 inches x 11 feet 1-1/2 inches (now in Antwerp Cathedral) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

On January 29, 1794, a branch of the French government appointed a commission of expert scientists and artists to forage for important monuments of art and science in Belgium. The commissioners were sent with guidebooks and instructions to select and confiscate sculptures, paintings, scientific instruments, books, and other cultural treasures. They seized objects from museums, churches, palaces, and private collections. These objects were then shipped to Paris and sent to the recently established Louvre Museum. Belgium became a prototype for the systematized art spoliations that the French would carry out in other territories they occupied.

The Italian Campaign

The French system of art appropriation was further refined by on the Italian peninsula. The intention was to make Paris the new artistic capital of Europe. In order to accomplish this monumental undertaking, Napoleon was supplied with a group of scientists and artists (as in the Low Countries), who were tasked with traveling with the French army to Italian states to research, select, and transport works of art to Paris.

In places such as Lombardy, the Veneto, and Emilia-Romagna, members of the commission were given unrestricted authority to select and requisition works of art just as they had in Belgium. Only in a few instances were cities treated mildly or spared art confiscations altogether (these were either in remote regions, which would have been difficult for the French army to reach, or Napoleon felt that their city officials would be an asset—this was the case with the king of Sardinia, who became an ally to the French).

This painting, The Wedding at Cana, by Paolo Veronese was created for a monastery in Venice in 1563. In 1797 the painting was confiscated, rolled up, and shipped to Paris. The painting remains in the Louvre today. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Territories that fought the French, such as Parma, Modena, and the Republic of Venice, were treated differently. When their city officials finally requested peace, Napoleon imposed a condition within the peace treaties that demanded the seizing of works of art from local churches, galleries, and princely art collections. These peace treaties were legally binding contracts and, thus, works of art transferred in this way were exempt from any potential requests for restitution. Historian John Merryman, who has studied the development of laws in the cultural heritage sector, noted that Napoleon’s unprecedented move to stipulate the transfer of works of art through peace treaties created a loophole that legitimized these confiscations from a legal standpoint.

The task of carrying out the confiscations as they were laid out in the treaties fell to the members of the commission. They collected the works of art listed in the treaties and, more significantly, determined which objects should be taken if a list had not been provided. Cities like Parma and Modena were to relinquish twenty paintings under the terms of their armistices (agreements), although the number of objects stipulated in the treaties could be amended at the request of the commissioners if they found further works that merited seizure. In the case of the Papal territories (in Italy), Napoleon promised not to march on Rome if the representative of Pope Pius VI agreed to sign over 500 manuscripts and 100 works of art, including statues, busts, and paintings.

This painting was taken to the Louvre and returned in 1815 to the Vatican (not Perugia from where it was taken). Pietro Perugino, Resurrection of Christ, 1499–1500, tempera gouache on wood (Vatican Museums)

The Pillaging of Perugia

A few Italian cities faced particularly egregious instances of pillaging. This was the case on March 3, 1797, in the Papal city of Perugia. Jacques-Pierre Tinet, a member of the commission, was sent to the city in search of works of art, books, manuscripts, scientific instruments, and other cultural objects. He did not restrict himself to seizing the Oddi altarpiece by Raphael, the Coronation of the Virgin by Giulio Romano and Giovan Penni, and the Resurrection of Christ by Pietro Perugino, which had been ceded through the Treaty of Bologna (1796) as reiterated in the Treaty of Tolentino (1797). Instead, Tinet visited churches, monasteries, convents, and city buildings, plundering everything he deemed to be of value.

Despite the fervent protests of the Perugians, and their efforts to conceal works of art, Tinet took an estimated thirty-one paintings, primarily by Raphael, Giulio Romano, Guido Reni, Federico Barocci, and Perugino. Although pillaging was often reserved as a punitive measure in cities that revolted against the French, that was not the case in Perugia, and the reasons for Tinet’s brazen pillaging remain unclear.

Also puzzling is the fact that over two-thirds of the paintings taken from Perugia were painted by the artist Perugino or students from his workshop. The reasons behind the appropriation of Perugino’s paintings are a mystery, as his work was not in vogue in France during the eighteenth century. According to the seventeenth-century French art critics Roger de Piles and André Félibien, Perugino’s major contribution was the role he played in shaping Raphael, his famous pupil, whose work was highly regarded by the French. The museum officials at the Louvre actively sought to include paintings by Raphael in their collection. The art historian Cristina Galassi has even suggested that Perugino’s paintings were seized because the commissioners had difficulty locating some of Raphael’s paintings. She argues that Perugino’s paintings were used as proxy for the work of his pupil.

Of the Perugino paintings taken from Perugia, at least three were altarpieces, which the French dismantled, crated, and then shipped to Paris. They included the San Pietro altarpiece (see top of page), the Sant’Agostino altarpiece, which was a collaboration with Giovan Battista Caporali, and the central panel from the Decemviri altarpiece, which was taken from the Palazzo dei Priori.

Hubert Robert, Project for the Transformation of the Grande Galerie, Musée du Louvre, c. 1796, oil on canvas, 115 x 145 cm (Louvre)

On arriving in Paris, the paintings were uncrated, inspected, and displayed in the Grande Galerie of the Louvre Museum. Visitors were encouraged to come and admire the recent spoils of the victorious French army. A few of Perugino’s paintings, such as the Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints (the central panel of the Decemviri altarpiece), were displayed in didactic panels alongside paintings by Raphael, including The Coronation of the Virgin, The Transfiguration, and the Belle Jardinière. The purpose of exhibiting the works of the master and the pupil side-by-side was to showcase Raphael’s early development under Perugino’s instruction and his later maturation as an artist.

Perugino, Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints (Decemviri altarpiece), 1495–96, tempera on wood, 193 x 165 cm (Vatican Museums but here photographed on view in the Palazzo dei Priori in Perugia; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Shortly after Napoleon was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo (1815), the pope and the central Italian princes sent Antonio Canova, the famous sculptor, to request the restitution of Italy’s treasures from the newly reinstated monarch, King Louis XVIII. The task was fraught with difficulties since the Italians lacked an army to press their claims. However, after some deliberation and the help of allies, Canova was successful in repatriating a group of significant cultural objects, including Perugino’s Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints—one of the two panels of the Decemviri altarpiece.

The French placed a condition on the return of the works of art—henceforth they had to be housed in a gallery made accessible to the public. The pope capitulated, and some of the objects were returned to Rome, where they were installed at the Vatican Museum. This was a point of contention, particularly for the city officials of Perugia, who expected that the works of art pillaged from their city, particularly Perugino’s Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints, would be returned to their original home.

The two panels of the Decemviri altarpiece recently reunited in the National Museum of Umbria, Perugia. Perugino, Madonna and Child with Saints Laurence, Louis of Toulouse, Ercolanus, and Constance, 1495–96, tempera on wood, 193 x 165 cm (Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-SA 2.0)

It was not until October 11, 2019 that The Lamentation of Christ and Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints, paintings which formed part of the Decemviri altarpiece, were finally reunited and installed in the Priori Chapel in Perugia for a special exhibition. This offered scholars a chance to study and enjoy the altarpiece, for a short time, in the location for which it was originally commissioned. The pinnacle, the central panel, the frame, and the moulding were reassembled for this exhibition, which was organized by the Vatican Museum and the National Gallery of Umbria and titled “The Magic of the Decemviri Altarpiece, Recreated in Perugia.”

While the recent reunion of the Decemviri altarpiece in Perugia may have sparked hope that the work would permanently be returned to its home in the Priory Chapel, officials at the Vatican Museum have not remarked on whether they will consider the option of restitution. Thus, the pieces of the Decemviri altarpiece seem fated to remain separate, not unlike the two other Perugino altarpieces, which were dismantled and taken from Perugia by the French in 1797. The paintings from the San Pietro altarpiece (top of page) and the Sant’Agostino altarpiece were dispersed among French regional museums in the early nineteenth century, where they have since remained.

Today, the fine arts museums in Nantes, Lyon, Bordeaux, Toulouse, Grenoble, and Rouen, display the disassembled altarpieces of San Pietro and San’Agostino. Indeed, it is unlikely that the many visitors who have enjoyed the splendid paintings of Pietro Perugino in French museums know that they were looted from Perugia.

The French government provided justifications for the art confiscations in Italy in the eighteenth century that are still used by museum officials today to argue for the retention of confiscated works of art such as Perugino’s paintings. Sadly, the lasting effects of these appropriations can still be observed today in some churches and public buildings of Perugia, which remain bereft of the treasures that had once adorned them.

Additional resources

Marie-Louise Blumer, “Catalogue des Peintures Transportées d’Italie en France de 1796 à 1814,” Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire de l’Art Français (1936), pp. 244–348.

Ferdinand Boyer, “Les Responsabilités de Napoléon dans le Transfert à Paris des Oeuvres d’Art de l’Étranger,” Revue d’Histoire Moderne et Contemporaine 11, no. 4 (1964), pp. 241–262.

Michael Broers, The Napoleonic Empire in Italy, 1796–1814: Cultural Imperialism in a European Context? (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005).

Ettore Camesasca, Tutta la Pittura del Perugino (Rizzoli Editore, 1959).

Andre Felibien. Entretiens sur les vies et sur les ouvrages des plus excellents peintres anciens et modernes. (Les Belles Lettres, 1987; original print,1666–1668).

Cristina Galassi, Il Tesoro Perduto: Le Requisizioni Napoleoniche a Perugia e la Fortuna della Scuola Umbra in Francia tra 1797 e 1815 (Perugia: Volumnia, 2004).

Cristina Galassi, “Le Requisizioni Francesi a Perugia di Jacques-Pierre Tinet 1797: le Opere Che Degne Saranno di Essere Raccolte per poi Trasportasi in Francia nel Museo della Repubblica,” Les Cahiers d’Histoire de l’Art, no. 1 (2003), pp. 141–154.

Vittoria Garibaldi, Perugino: Catalogo Completo (Produzioni Editoriali Associate, 1999).

David Gilks, “Attitudes to the Displacement of Cultural Property in the Wars of the French Revolution and Napoleon.” The Historical Journal 56, no. 1 (March 2013), pp. 113–143.

Cecil Gould, “The First Italian Campaigns,” in Trophy of Conquest: The Musée Napoléon and the Creation of the Louvre (Faber and Faber, 1965), pp. 41–66.

Cathleen Hoeniger, “Art, Science and Painting Restoration in Napoleonic Italy, 1796-1798.” In Conservation in the Nineteenth Century: Early Techniques in the Conservation of Cultural Objects, edited by Isabelle Brajer (Archetype Press, 2013), pp. 15–28.

Cathleen Hoeniger, The Afterlife of Raphael’s Paintings (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Barbara Jatta and Marco Pierini, La Pala dei Decemviri di Pietro Perugino. Perugia: Aguaplano Libri, 2020, published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same title, organized and presented at the Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria and Musei Vaticani (October 11, 2019–June 26, 2020).

Christopher Johns, Antonio Canova and the Politics of Patronage in Revolutionary and Napoleonic Europe (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1998).

Joseph Jérôme Lefrançois de Lalande. Voyage d’un François en Italie, fait dans les années 1765 & 1766 (Paris: Desaint, 1769).

Andrew McClellan, “For and Against the Universal Museum in the Age of Napoleon,” in Napoleon’s Legacy: the Rise of National Museums in Europe, 1794–1830, edited by Ellinoor Bergvelt, Debora Meijers, Lieske Tibbe, and Elsa van Wezel (Kulturbesitz and G+H Verlag, 2009), pp. 91–100.

Andrew McClellan, Inventing the Louvre: Art, Politics, and the Origins of the Modern Museum in Eighteenth-Century Paris (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994).

John Merryman, “Plunder, Reparations, and Destruction,” in Law, Ethics and the Visual Arts, edited by John Merryman, Albert Elsen, and Stephen Urice (Alphen aan den Rijn: Kluwer Law International, 2007), pp. 1–112.

Michelle O’Malley, “Quality, Demand, and the Pressures of Reputation: Rethinking Perugino.” The Art Bulletin 89, no. 4 (Dec. 2007), pp. 674–693.

Baldassarre Orsini, Guida al forestiere per l’augusta città di Perugia, al quale si pongono in vista le piu eccellenti pitture, sculture ed architetture, con alcune osservazioni (Perugia: Presso il Costantini, 1784).

Roger de Piles, Abregé de la vie des peintres avec des réflexions sur leurs ouvrages et un traité du peintre parfait, de la connoissance des desseins (Olms Verlag, 1969; original print, 1699).

François René Jean de Pommereul, Campaign of General Buonaparte in Italy, in 1796–77, by a general officer, translated from the French and continued to the Treaty of Campo Formio by T. E. Ritchie (Geo, Reid and Co. Printers, 1799).

Antoine Chrysosthôme Quatremère de Quincy, Letters to Miranda and Canova on the Abduction of Antiquities from Rome and Athens, introduction by Dominique Poulot, translated by Chris Miller and David Gilks (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2012).

Dorothy Louise MacKay Quynn, “The Art Confiscations of the Napoleonic Wars,” The American Historical Review 50, no. 3 (April 1945), pp. 437–460.

Adamo Rossi, “Documenti Sulle Requisizioni dei Quadri Fatte e Perugia dalla Francia ai Tempi della Pubblica e dell’Impero,” Giornale di Erudizione Artistica 5 (1876), pp. 234–244.

Wayne Sandholtz, “Napoleonic Plunder and the Emergence of Norms,” in Prohibiting Plunder: How Norms Change (Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 47–70.

Pietro Scarpellini, Perugino (Electa Editrice, 1984).

Caterina Zappia, “La Sfortuna di Perugino nella Francia dell’Ottocento,” in Perugino: il Divin Pittore, edited and curated by Vittoria Garibaldi, Francesco Federico Mancini and Clara Cutini (Silvana Editoriale, 2004), pp. 403–415.