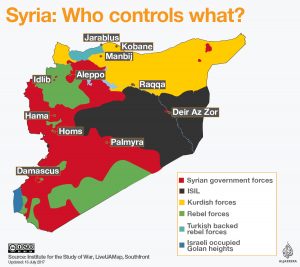

“Conflict Antiquities: A Terrorist Financing Risk,” The Guardian, June 15, 2014

In June 2014 the Guardian newspaper ran a story claiming that the terrorist organization Daesh had made $36 million from antiquities sales in the al-Nabuk area of Syria, and that it obtained a major part of its funding from antiquities sales more generally.

Almost overnight, this story transformed the antiquities trade in the public imagination from being a crime against culture into a crime against humanity. If the headlines that followed over the following weeks and months were anything to go by, vast sums of money were being directed from the antiquities trade into the war chests of Daesh and other armed terrorist and insurgency groups. Something needed to be done. It was a compelling narrative, one that played out well with the media-malleable public, and it certainly hooked the attention of concerned policy-makers, but for many long-time experts in the field it just did not ring true.

Fantasy economics

In the first place, the idea that $36 million could be made over the period of a year or so actually within Syria was unprecedented, unbelievable even. Many studies had shown that the monetary value of antiquities close to their source is only a small and even a vanishingly small percentage of their value on the destination market in places like London and New York.

In 1972, for example, The Metropolitan Museum of Art paid antiquities dealer Robert Hecht one million dollars for a Euphronios Attic red-figure krater. The tombaroli who stole the krater from an ancient Etruscan tomb in Italy are believed to have received the equivalent of $88,000 for their labors—only nine percent of its final price. Such markups are typical. So, if the story was to be believed, antiquities worth $36 million on the ground in Syria would be worth a staggering $360 million on the destination market, perhaps much more. It was fantasy economics. There was no evidence for that kind of market activity and the reality had to be something less spectacular.

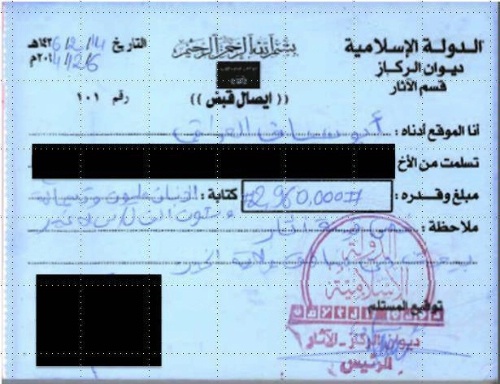

Daesh receipts for payment of “war booty” tax (source: U.S. Department of State)

The Guardian figure was never corroborated, but a more accurate assessment was achieved when in May 2015 United States Special Forces seized a book of receipts during a raid on the Syrian headquarters of Abu Sayyaf, the head of Daesh’s antiquities division. These receipts suggested that Daesh might be making something like four million dollars a year from the antiquities trade. A large and worrying sum, but nothing like the figure first suggested, and one that would account for only about one percent of Daesh’s total income.

Antiquities trafficking is nothing new

Terrorists and insurgents profiting from antiquities trafficking was nothing new. What was new was the sensationalist reporting. In the 1990s, for example, it was well known that mujahideen and later Taliban groups inside Afghanistan were making money from the antiquities trade, but this never made the headlines.

More than Just Digging: Daesh Antiquities Trafficking an Institutionalized Process, infographic from The Antiquities Coalition

Before that, in the 1970s, combatant factions in the Cambodian civil war, including after 1990 the Khmer Rouge, had been likewise engaged. It is believed, for example, that the Khmer general Ta Mok, the so-called “Butcher of Cambodia,” had held a central organizing role in the Cambodian antiquities trade.

During the early 1980s, until his fall from favor in 1985, Bashar al-Assad’s uncle, Rifaat al-Assad, controlled the antiquities trade in Syria, and his counterpart in Iraq was perhaps Saddam Hussein’s brother-in-law Arshad Yashin, who is said to have organized much of the looting there. Violence was a growing accompaniment to the antiquities trade during this period. In late-1990s Iraq, guards were killed in gun battles while trying to protect sites. In 2005, while transporting arrested antiquities dealers, eight Iraqi customs officers were ambushed and shot dead. So while it might be an exaggeration to report the antiquities trade as a crime against humanity, it is a violent enterprise, and one that profits armed and criminal organizations alike.

Statue found during the raid on Abu Sayyef’s headquarters (source: U.S. Department of State)

Why did we fail to protect Syria’s cultural heritage?

The real surprise and indeed outrage of the Daesh involvement with the trade was that it was happening at all. The threats posed by antiquities trafficking to cultural heritage and more broadly to society at large had been known since at least the 1960s, when the international community had supported the drafting and subsequent adoption of the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. For the first time, the antiquities trade was recognized internationally as a harmful enterprise and one that needed to be controlled. Since then, there has been a proliferation of conventions, recommendations and actions aimed at combatting the trade and protecting cultural heritage. So why, 45 years later in 2015, was the antiquities trade devastating Syrian cultural heritage? Had the international policy response failed? What had gone wrong?

A rise in consumer demand

The answers to these questions are to be found in the nature of the policy response. The antiquities trade is fueled by consumer demand. Antiquities are bought by museums and private collectors in the rich acquiring countries of the destination market.

Antiquities found during the raid on Abu Sayyef’s headquarters (source: U.S. Department of State)

Yet international policy has never quite come to grips with tackling demand and reducing the attractive pull of museums and collectors. Instead, its focus has been on protecting cultural heritage at source and reducing the flow of antiquities onto the destination market. Yet it is an impossible task to protect every cultural site in the world, particularly in poor countries unable to afford the required infrastructure, or in countries suffering from war or civil disturbance where public order has disintegrated. Only when collectors can be convinced to stop buying antiquities will thieves and traffickers stop selling them.

Museums in the spotlight

Back in the 1960s, when the 1970 UNESCO Convention to prevent the illegal trafficking of cultural property was being drafted, museums were believed to be the mainspring of demand. And perhaps they were. There has been a concerted effort since then to develop ethical guidelines discouraging museums from acquiring trafficked antiquities. The work of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) has been particularly notable in this regard.

The Euphronios Krater at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2006 (photo: Tim Pendemon, CC BY 2.0)

Yet following investigations by Italian and Greek law enforcement authorities, the museums world was rocked during the 1990s by revelations that major US art museums had been actively acquiring stolen and trafficked antiquities. Museums such as the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York were forced to return important antiquities to Italy and Greece, including the Euphronios krater.

But the bad news didn’t stop there. In the 2010s, police and customs officials in India and the United States broke up a major trafficking operation headed by New York-based dealer Subhash Kapoor. He was shown to have sold a large Chola bronze Shiva Nataraja, which had been stolen from a temple in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu only two years earlier, to the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) for five million dollars. The NGA returned the Nataraja to India in 2014. Kapoor had sold other antiquities from the same temple thefts to Singapore’s Asian Civilizations Museum and the Toledo Museum of Art. The case triggered an independent review of the problematic histories of 36 antiquities acquired by the NGA between 1968 and 2013.

Museums, clearly, are still an important component of demand. They act materially by making big money purchases and acquisitions, but also set a moral tone when they seem to make indiscriminate collecting socially acceptable.

Booming demand

Nevertheless, by the time of Kapoor’s arrest, museums were not the only destination for trafficked antiquities. Antiquities were being touted as tangible assets for canny investors, and they had become trendy ornaments for interior-design makeovers. Antiquities from Middle Eastern countries were being marketed as “relics” from the “Holy Land,” and the meditative worth of Buddhist antiquities similarly attracted more spiritual collectors. The rapid expansion of the internet as a means for trading antiquities created a market for smaller and less-valuable pieces that would previously not have been worth looting. Demand was booming like never before, and was largely out of control.

Successful indictments and convictions of offenders for antiquities trafficking were so rare as to be almost non-existent. Even when convictions did happen, sentencing was light and failed to pose any serious deterrence. In 2012, two U.S.-based dealers pled guilty to offenses related to antiquities trafficking. One was sentenced to six months’ home confinement and one year’s probation, the other was fined $1,000. Within a couple of years, they were both back in business.

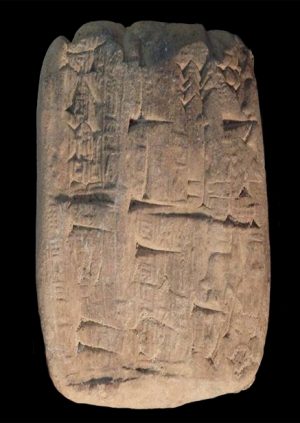

Cuneiform tablet illegally imported by Hobby Lobby (source: U.S. Attorney’s Office)

Missing evidence

Trafficked antiquities are routinely sold without documented evidence or even with fraudulent evidence of ownership history—so-called “unprovenanced” antiquities. The problems facing law enforcement authorities who must try to establish provenance were made abundantly clear in July 2017 when it was announced that Hobby Lobby had agreed to pay a $3 million forfeiture to the United States government and relinquish claims to and possession of 3,599 Iraqi antiquities bought in 2010 for 1.6 million dollars. Knowledgeable observers believed the antiquities to have been stolen from Iraq, and that someone should have faced a felony charge for the theft. But the evidence was not there. Theft could not be proved. Instead, Hobby Lobby was punished for customs violations.

Hobby Lobby is owned by the Green family, which in 2009 established the Green Collection of antiquities and other objects related to biblical history, and the Green Scholars Initiative of university academics to study them. As the 2017 forfeitures showed, much of the unprovenanced material being studied by the Green Scholars is likely to have been trafficked.

The Green scholars are not alone. A new academic industry has developed, comprised of university scholars studying suspect antiquities acquired by large private collections. Ancient manuscripts and other text-bearing antiquities, many of them from Egypt, Iraq, Afghanistan, Israel, and Palestine, are particularly worthy of attention. Scholarship establishes the importance and authenticity, and thus monetary value of studied material—to the financial benefit of the collector. In 2007, for example, a U.S.-based private collector claimed a $900,000 tax deduction for a donation of 1,679 Iraqi cuneiform tablets to Cornell University. He had purchased the tablets sometime during the 1990s for $50,000. The mark-up in price must have been due to scholarly study over the intervening period that had established their importance—and their value.

How do we stop trafficking?

Antiquities trafficking damages cultural heritage worldwide, and the proceeds from trafficking fund organized crime and terrorist violence. No one has to buy unprovenanced antiquities. Antiquities collecting does not confer cultural sophistication and antiquities are not good investments . Antiquities trafficking will only stop when people stop buying them.