The art of this century is commonly referred to as “Baroque” and some scholars see it as the first truly global style. When we use the term “global” we don’t mean that the entire world was connected, but that some distant geographies were connected by pathways that were defined by the contours of religion, colonization, and trade.

Asia and Africa (detail), Andrea Pozzo, Glorification of Saint Ignatius, 1691–94, fresco, nave vaulting, Sant’Ignazio, Rome

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Catholic church suffered a significant loss of territories and influence as a result of the Protestant Reformation, but nevertheless claimed a broad global mandate. In Rome, Gianlorenzo Bernini created triumphal works that erased the distinction between painting, sculpture, and architecture and that celebrated the power of the papacy. In a Jesuit church in Rome, Fra Andrea Pozzo depicted allegorical figures of the four continents, Asia (riding a camel), the Americas (bare-breasted with an arrow and feathered headdress), Africa (with Black skin, riding a crocodile), and Europe (with symbols of royalty—an orb, scepter, and crown) in a breathtaking ceiling painting. The implication is clear—Europe (and the Catholic church) saw itself as destined to rule the world.

Peter Paul Rubens, Elevation of the Cross, from Saint Walburga, 1610, oil on wood, center panel: 15 feet 1-7/8 inches x 11 feet 1-1/2 inches (Antwerp Cathedral; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In Antwerp (today in Belgium), Rubens was commissioned to paint altarpieces celebrating the city’s return to Catholicism after a period of Protestant control during which vast numbers of religious images were destroyed. More than a century of religious wars in Europe between Catholics and Protestants resulted in much of Northern Europe becoming Protestant, while the countries we know as Spain, France, and Italy remained Catholic.

The 17th century is often called the “Golden Age” of the (Protestant) Dutch Republic (on the map above “The United Provinces”), and that is due in part to Dutch trade and colonialism in Asia. Thanks in part to the wealth generated by the Dutch East India Company, there was an unprecedented demand for images back in the Netherlands. One result of this is the emergence of new subjects including genre scenes, still lives, landscape, and the proliferation of portrait painting, including a new format, the group portrait. Rembrandt’s famous Night Watch is perhaps the best-known example. In the Dutch Republic while there are still important patrons, artists are increasingly working for the open market making up, to some extent, for the loss of church patronage.

The choice to not show the artists at work, but rather as fashionable gentlemen engaged in sociable intellectual exchange, speaks directly to the early history of the French Royal Academy. Jean-Baptiste Martin, A Meeting of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture at the Louvre, c. 1712–21, oil on canvas, 30 x 43 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

In France, an important development in the history of art was the establishment of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in 1648, an extension of royal power in the realm of art. The Royal Academies of France and Britain helped to establish the centrality of visual culture but also set up rigid hierarchies about what they deemed the best art.

By the late 17th century, slavery in the thirteen British colonies in North America had several unique characteristics compared to slavery in other times and places. First, slavery was for life: enslaved people had no possibility of becoming free except by escape, self-purchase (which was rare), or by manumission. Second, it was heritable: an enslaved woman’s children were also enslaved for life, regardless of the status of their father. Lastly, and most importantly, slavery became race-based: Africans or Afrodescendants were subject to enslavement, and white people were not.

Though separated by the Pacific Ocean, the Philippines and Mexico were both part of the Spanish Empire. Beginning in the 16th century, Spanish galleons (large, multi-decked ships) began to sail between Manila (in the Philippines) and Acapulco (in Mexico). This trans-Pacific Manila Galleon trade created an important route for the global exchange of materials (such as silk, spices, porcelain, and ivory from Asia and silver and gold from the Americas). Many of the resources and goods coming from Asia would also travel overland from Acapulco to the Gulf Coast of Mexico, at which point they would be shipped across the Atlantic Ocean to Spain. An ivory image of the crucified Christ traveled between three continents, demonstrating the global flow of materials, objects, and Christianity in the 16th and 17th centuries. A Japanese-style screen, a biombo, utilizes Indigenous art techniques of Mexico. It depicts the conflict between the Hapsburg dynasty in Europe and their foe the Ottomans (in what is today Turkey). So in this work of art, Japan, Mexico, Austria, and Turkey come together, forming a truly global work of art.

Installation of the reconstructed Gwoździec synagogue ceiling and bema in the POLIN Museum of the History of the Polish Jews, 2013, Handshouse Studio (photo: Magdalena Starowieyska and Dariusz Golik, CC BY-SA 3.0 PL)

It’s important to remember that these examples of material culture represent only a fraction of the work that had been produced. So much art was lost during the Early Modern period for a variety of reasons. For example, a remarkable painted wooden synagogue, the Gwoździec synagogue, in present day Ukraine, is the only remaining example of upwards of 200 painted synagogues built across Eastern Europe (those that survived into the 20th century were destroyed by the Nazis).

The rulers of the Mughal Empire, which controlled much of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries, were also global in their outlook. In 1579, the first Jesuit mission arrived at the Mughal court and introduced Christian ideas and symbols at the request of the Mughal Emperor Akbar. As a result, Mughal artists absorbed artistic conventions from European art and even painted Christian subject matter. A major tradition of miniature painting emerged in the royal workshops that embodied a vast range of influences.

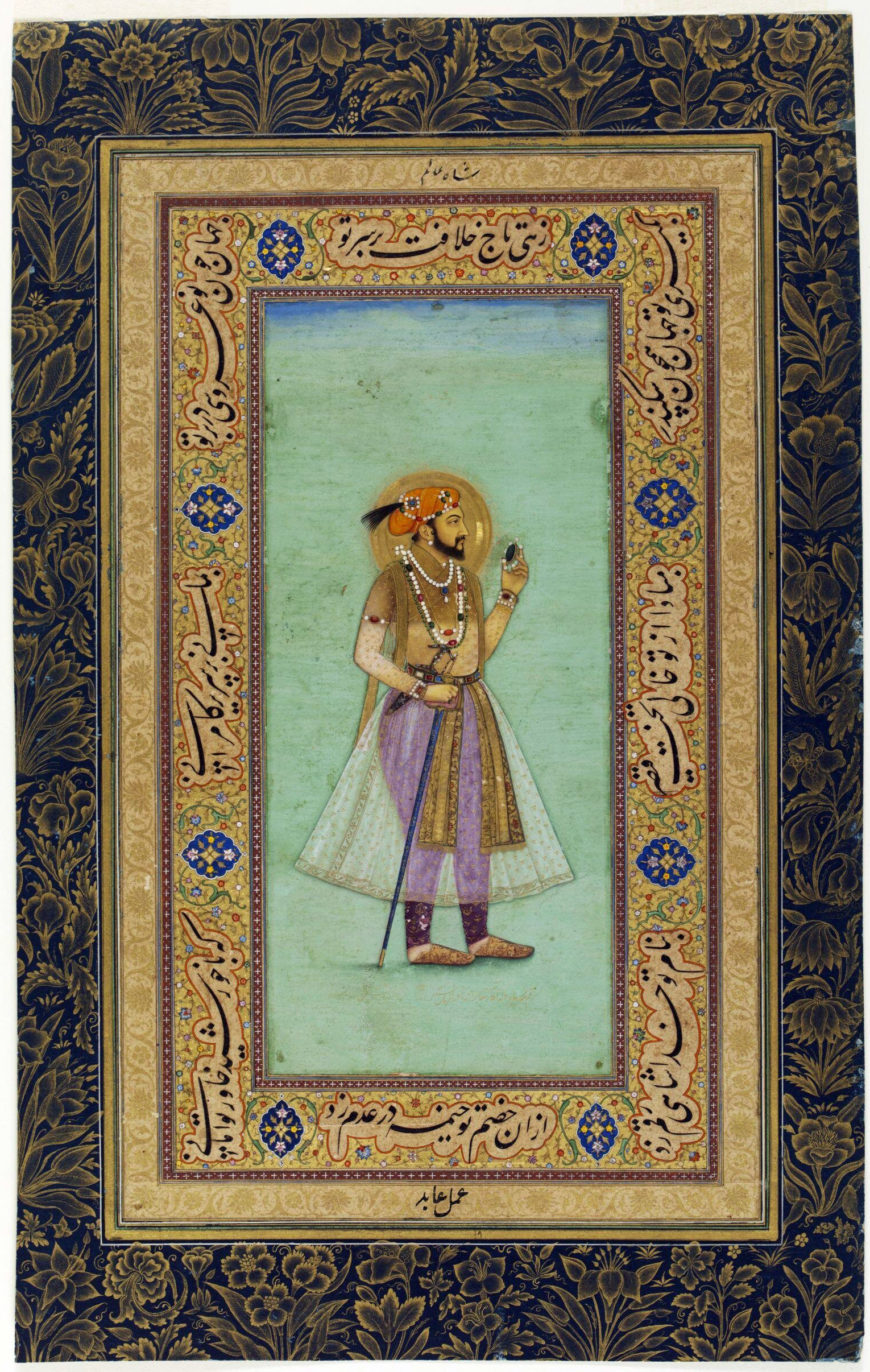

Muhammad Abed, Shah Jahan holding an emerald, 1628 (dated regnal year 1; India), 21.4 x 9.5 cm (Victoria & Albert Museum, London)

In an accession portrait, the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan holds a large emerald, likely mined in one of the Spanish colonial territories in South America. The emerald was seen as exotic and exciting, and linked to the Mughals’ desire to collect objects from around the world. These small scale objects of beauty were matched by far larger projects including the Taj Mahal built by Shah Jahan to honor his late wife.

But the Mughals weren’t the only ones collecting. The impulse to amass foreign goods makes sense in this period of globalization. Showing off knowledge about unfamiliar places was popular among elites like the Medici family in Florence. There were new materials, new technologies, new animals, new foods, new gods, new ways of representing deities, and new ways of building. And there were many ways of showcasing this influx of newness. A coconut imported from Indonesia to Holland was encased in silver and decorated with an image of the pagan god Neptune. Christian images were made using feathers in a technique developed by the Indigenous people of Mexico. A ruler in Europe fascinated with Asian ceramics commissioned hundreds of large-scale porcelain animals for a gallery in his palace to supplement his collection of thousands of Japanese and Chinese porcelains. Smaller collections were displayed in a Cabinet of Curiosities or select objects could be gathered together and immortalized in a still-life painting.

Two artists, both women, are also representative of the broad curiosity of this era. At a time when it was still believed that butterflies or moths spontaneously generated from piles of dung, Dutch painter Maria Sibylla Merian raised caterpillars, carefully observed their development and illustrated the stages of metamorphosis for the first time. Rachel Ruysch, one of the highest paid artists during the late 17th and early 18th centuries, painted carefully observed still lives, mostly of flowers and insects. This new interest in direct observation (instead of relying on the teachings of the church or ancient authorities) can also be seen in Rembrandt’s painting of The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp and in England with the work of Sir Francis Bacon, who advocated for an institution that would promote and regulate the acquisition of knowledge derived from observation (the Royal Society for Improving Natural Knowledge).

Over the years, art historians have defined the Baroque style in different ways. Some have related the style to developments in science (the direct observation of nature promoted by thinkers such as Francis Bacon). Change and movement is almost always seen in the paintings, sculptures, and architecture of this period—a perfect expression of the dramatic transformations the world was then undergoing.