American colonies

The early decades of the seventeenth century was a time of great cultural collision between several European powers in North America and the indigenous peoples who had occupied the continent for millennia.

Whereas generations of previous scholars have referred to this historical era as “Colonial America,” more recent writers have instead embraced the term “American Colonies.” Although this is a subtle change, it is an important one. Whereas Colonial America suggests a kind of singularity, American Colonies reinforces the plurality of those who came to settle on the Eastern seaboard in the larger context of North America.

Robert Walter Weir, Embarkation of the Pilgrims, 1857, oil on canvas, 122.2 x 183.5 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Indeed, different groups of people came to differing parts of North America for a variety of distinct reasons. The Spanish conquistador Pedro Menendez de Aviles founded St. Augustine (in what is now Florida) in 1565. Samuel de Champlain founded the French colony of Quebec on the shores of the St. Lawrence river on 3 July 1608. The Dutch West India Company founded New Amsterdam (now New York) in July 1625.

John Smith founded the first English colony in Jamestown (named after King James I) in Virginia (named in honor of Queen Elizabeth I, the “Virgin Queen) in 1607. In the three decades that followed, other colonies began to dot the eastern seaboard.

The Pilgrims, Puritans led by William Bradford, landed at Plymouth Rock in what is now Massachusetts in 1620 and established Plymouth colony. In April 1630, a fleet of ships, with John Withrop and 700 colonists on board, embarked for New England, arriving in Salem that June. They established the Massachusetts Bay colony. Subsequent years saw the founding of Maryland (1632), Rhode Island (1636), and Connecticut (1636).

Why they came

Although these English colonies are united by a common language, they greatly differed in regards to the reason they were founded, who was attracted to settle them, and the religious affiliation of those colonialists. For example, Jamestown was not initially intended to be a lasting, permanent settlement—the initial envoy contained 105 men and 39 boys, but not a single woman.

The primary goal for this group of adventurers was to generate a profit, presumably through the discovery of gold, for the Virginia Company of London, the chartering company that financed the colony. Within a decade, those who had survived horrifically lean years had learned to harvest tobacco, a cash crop if ever there was one.

Die Proof of the postal stamp “Founding of Jamestown,” issued 1907 (Smithsonian National Postal Museum)

In the years that followed, those without — or without access to — family wealth arrived on the shores of Chesapeake Bay in search of their own fortunes. Because the overwhelming majority of those who landed in Virginia were Anglican, that is, belonging to the Church of England, it is clear that Virginia’s growth during the seventeenth century was largely the result of economic aspirations.

Map showing the Chesapeake Bay drainage basin (image: Kmusser, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In contrast, the Puritans who voyaged to New England did so not for material wealth, but in order to escape the religious persecution they had faced in England. Because the Puritans who immigrated to the New World did so in order to create a new, more perfect settlement (as opposed to financially exploit a new land), they closely recreated the patriarchal family structure that had been a part of their English roots. The Puritans believed this male-centered society mimicked God’s authority in the divine world and the supremacy of government in ours.

In time, Chesapeake Bay would develop immense tobacco plantations owned by the economic elite, and the lives of the colonists in New England would be defined by religious leadership and an increasingly wealthy merchant class.

The beginnings of slavery in the colonies

These regional differences, from the more densely populated areas of New England to the agrarian plantations in the tidewater area in Virginia, had profound repercussions as it pertains to the development of labor and the workforce. In many southern colonies, the need for labor far exceeded the supply that was then available. As a result, two related systems developed, rose to prominence, and were exploited in order to provide that labor: indentured servitude and slavery.

Although indentured servitude existed in the north, it was in the south (and particularly in the tidewater of Virginia) where it was most prevalent. There was more work to do than bodies to do it (in Virginia), and more (young) workers than quality jobs (in England). The able-bodied could sell their future labor — generally, but not always, seven years’ worth — for the cost of the westward voyage across the Atlantic Ocean, and then food and shelter once they arrived.

Although some women made this bargain, the majority of indentured servants were male. At the conclusion of their time of indenture, be it seven years or another amount, the person was free to seek other (that is, paid) employment.

Historians date the beginning of Colonial America to 1607 with the founding of Jamestown. It was not long after — less than 12 years — for enslaved Africans to be forcibly brought to Virginia. In August 1619 (400 years ago), the frigate White Lion, set ashore in Jamestown with 20 men and women from what is now Angola in southern Africa.

During the first part of the seventeenth century, African slaves were treated somewhat like indentured servants—their more willing European counterparts. As the seventeenth century progressed, however, Virginia introduced a variety of laws that increasingly codified forced slavery and transitioned African — who had a hope for freedom after seven years — to a life sentence of slavery, both for themselves and their born (or as yet unborn) children. The owning of African slaves spread rapidly, and in 1661, a law was passed that allowed any free (White) person to own slaves.

A global trade had already developed around sugar in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, bolstered by the growing popularity of tea, coffee, chocolate, and punch in Europe, that depended on the labor of enslaved people. It would take centuries and the American Civil War (1861–65), to finally dismantle the institution of slavery.

At the end of the seventeenth century, however, the enormous size of the tobacco and, increasingly, cotton plantations required more labor than the owners were willing to pay for, and as a result, the barbaric treatment of fellow human beings that had begun soon after the founding of Jamestown was vastly expanded.

The French and Indian War (Seven Year’s War)

We do not get everything right when it comes to our understanding of history. For example, many think of World War I (1914–18), as the first global conflict. However, the first war waged on numerous continents by a variety of world powers, was not fought early in the twentieth century, but rather was the Seven Years’ War (1756–63). This was a global conflict that had its genesis in 1754 in what American historians call the French and Indian War.

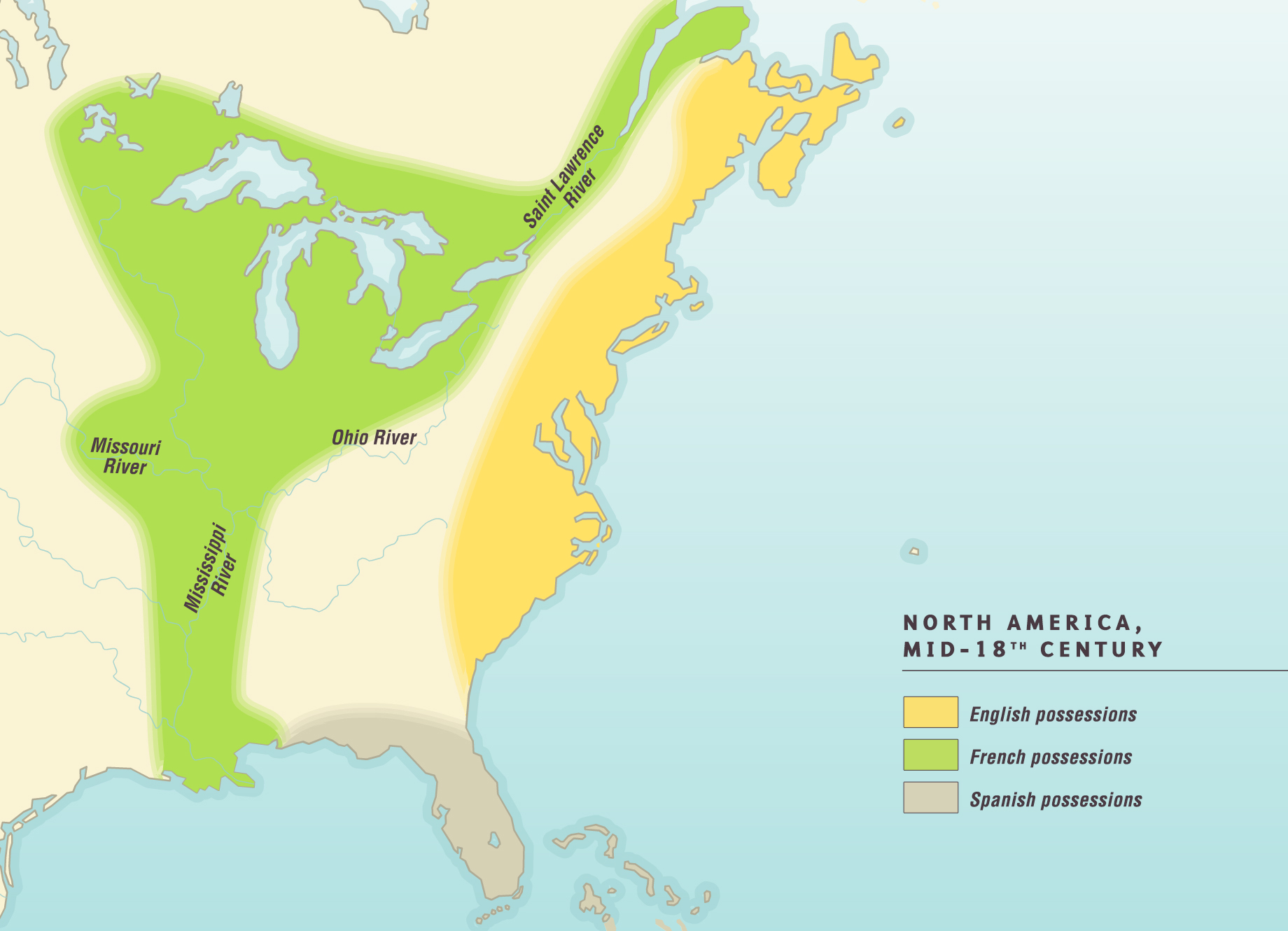

By the middle of the eighteenth century, the American colonies, and particularly those owned by Britain and France, had expanded to such an extent that there was tension along the borders of each countries’ purported borders. The British laid claim to the Atlantic seaboard from what is now Maine to Georgia, and France asserted ownership of what is now eastern and central Canada, the Ohio River Valley, and the area surrounding the Mississippi River (the state of Louisiana is named after the King of France, Louis XIV).

Map courtesy of The Map as History. For a complete catalogue with over 200 videos, please visit the website, © The Map as History (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License)

The French began to fortify their possessions through the construction of military forts, and this agitated the British settlers who were flooding into the fertile and largely unsettled land of the Ohio River Valley, parts of what are now Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Indiana.

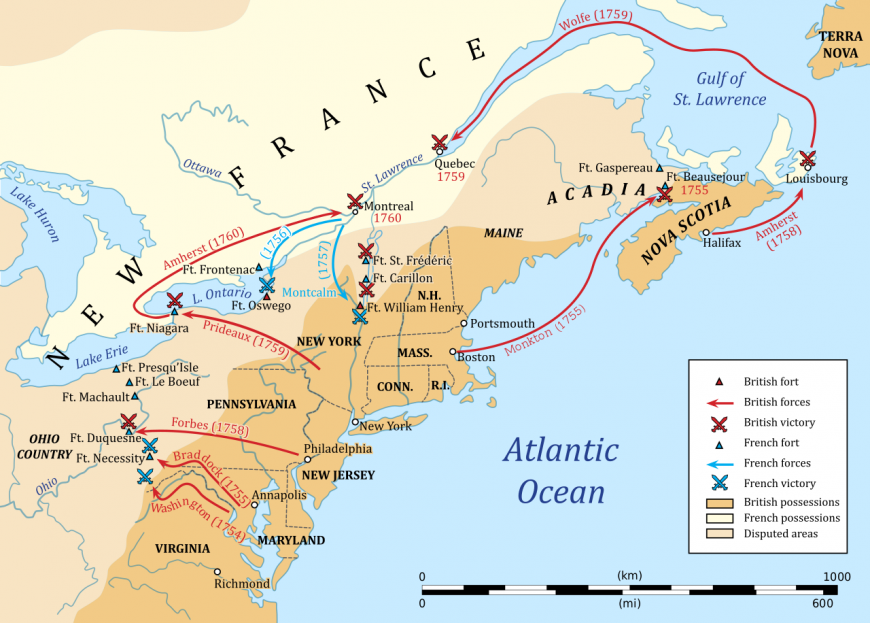

In 1753, Robert Dinwiddie, the Lieutenant Governor of the Virginia, sent a young militia officer by the name of George Washington — yes, that George Washington — to the French Fort Le Boeuf, just south of Lake Erie, requesting that the French surrender and abandon their military post.

The French, confident in their position and unwilling to leave, sent Washington away. After he reported this news to Dinwiddie upon his return to Virginia in January 1754, the Lieutenant Governor sent a militia force to the “Forks of the Ohio,” the place where the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers conjoin to become the Ohio River. The mission: to construct Fort Prince George.

Bricks mark the outline of the former Fort Duquesne, Point State Park, Pittsburgh (photo: Kevin Myers, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Construction of this fort had begun by 17 February 1754, but about two months later, a French officer (Claude-Pierre Pécaudy de Contrecœur) led a battalion to seize the unfinished Fort Prince George from the British. Afterwards, the French continued this fort’s construction and renamed it Fort Duquesne.

Map of the French and Indian War (image: Hoodinski, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The lead up to revolution

In order to halt construction, the recently promoted Colonel Washington was dispatched with a small troop under his command to reacquire the fort. Washington and his men ambushed a 35-man French detachment on 28 May 1754. The British killed ten of these French soldiers, including the commanding officer, Joseph Coulon de Villiers, de Jumonville at what is now called the Battle of Jumonville Glen.

This small skirmish, which lasted no more than 15 minutes, is generally credited as the beginning of the French and Indian War and the larger Seven Years’ War. A brief encounter with truly great effect. Ultimately, the global conflict known as the Seven Years’ War would strain on the coffers of the British treasury. To recover those losses, the British Crown turned to their colonial subjects in the New World. The colonists would not be pleased with the taxation that followed.