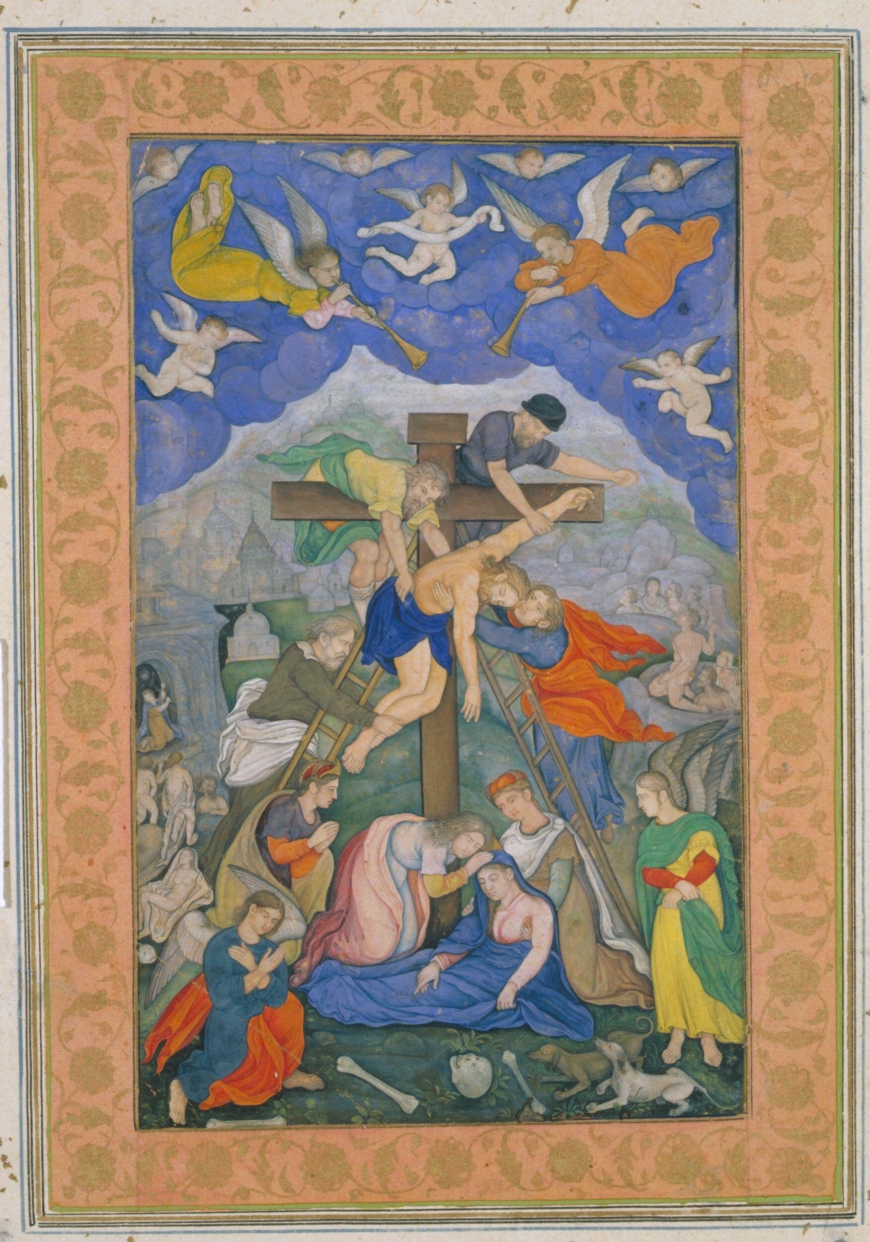

Unidentified artist, The Deposition from the Cross, late 16th century, gouache on paper, 19.4 x 11.7 cm (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Would you have guessed that an Islamic patron commissioned this painting of a scene that is popularly associated with Christian art?

This 16th-century painting of Christ being removed from the cross was produced for the Mughal Prince Salim—later known as Emperor Jahangir—while he lived in Lahore, the Mughal Empire’s Northern capital, in present-day Pakistan.

Before we get into why an Islamic ruler would commission an image like this, let’s take a closer look at the painting to see how its maker, an unknown artist in Jahangir’s atelier, not only depicted a Christian scene but also borrowed stylistic conventions from European artistic traditions.

At the center of the painting, we see the cross with two ladders resting against it. One figure uses a pincer to remove the final nail securing Christ to the wooden beam. Three other figures, including two men who have ascended the ladders, support Christ’s body to lower it gently. The drooping yet elegant curve of Christ’s figure is paralleled by the posture of the Virgin Mary—depicted in deep blue robes—who has collapsed in grief directly below him. Angels and three robed women, known as the Three Marys, comfort her. One of them is depicted in a stance that mirrors the Virgin.

Marcantonio Raimondi after Raphael, Descent from the Cross, 1520–21, engraving, 41 x 29 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum, London)

While the solidity of the cross at the center of the image draws the eye, the distribution of figures, the fluid drapery, and the various curves and contours seen across the work come together to lend a sense of balance to its dynamic composition.

In the foreground, two dogs crouch near bones and a skull, symbolizing Golgotha or the Place of Skulls, the site of Christ’s crucifixion. In the background, a city is rendered in muted colors that contrast with the blue clouds in the sky above, where two flying angels blow trumpets to signal Christ’s entry into heaven. The central cherub holding a paper scroll and the hovering heads of winged putti (angelic beings portrayed as male children) are symbols that affirm the omnipresence of God.

This scene has been portrayed extensively across Byzantine, Renaissance, and Flemish art (both in prints and paintings), which was introduced to Mughal and Deccan workshops by Jesuit Missionaries from the late 1500s onwards (more on that, later). The composition of this particular painting, too, is based on an engraving by the Italian artist, Marcantonio Raimondi, likely after a lost painting by Raphael (the Italian Renaissance painter).

Why were Mughal artists referencing European engravings?

The Mughal rulers were avid collectors of objects and curios from foreign lands; from Chinese porcelains to Colombian emeralds, the ownership of luxury goods and rare objects from foreign lands was a marker of status, wealth and cosmopolitanism. Emperor Jahangir actively collected European paintings and prints, among other things. He wasn’t simply a collector; he was also curious about these objects and what they represented. Father Jerome Xavier, for example, writes that Emperor Jahangir had ordered his librarian at Lahore to fetch albums of European engravings to have Xavier and other Jesuit fathers explain the iconography and allegorical meanings of the paintings to him. Xavier even recorded instances of artists in Jahangir’s painting workshops copying some of these works.

The interaction between Jesuit priests and the Mughal rulers wasn’t new, it dates to before Jahangir’s rule. In fact, Jahangir’s father, Emperor Akbar, a tolerant man with an interest in religions, art, and literature (despite being illiterate himself), sent a Mughal embassy to the Portuguese colony of Goa in southern India in 1579, out of a curiosity that reflects his broader pluralistic outlook. The ambassador carried a letter from Emperor Akbar to the viceroy and another to the “Chief Fathers of the Order of St Paul,” requesting them to send “two learned priests” to the Mughal court, as well as “the principal books of the Law and the Gospel,” to teach and discuss with Akbar “the Law and what is most perfect in it.”

In response, the first Jesuit mission of three Jesuits arrived at the Mughal court in 1580 and remained there until 1583. They introduced the Mughals to Christian symbols, icons, figures, and motifs, such as haloes, angels, cherubs, the Madonna, and Christ himself. This fateful encounter, between the Mughal court and the Jesuits, would lead to multiple instances of the Mughal artists absorbing painterly conventions from European art and explicitly engaging with Christian subject matter—examples of which we look at closely in this article.

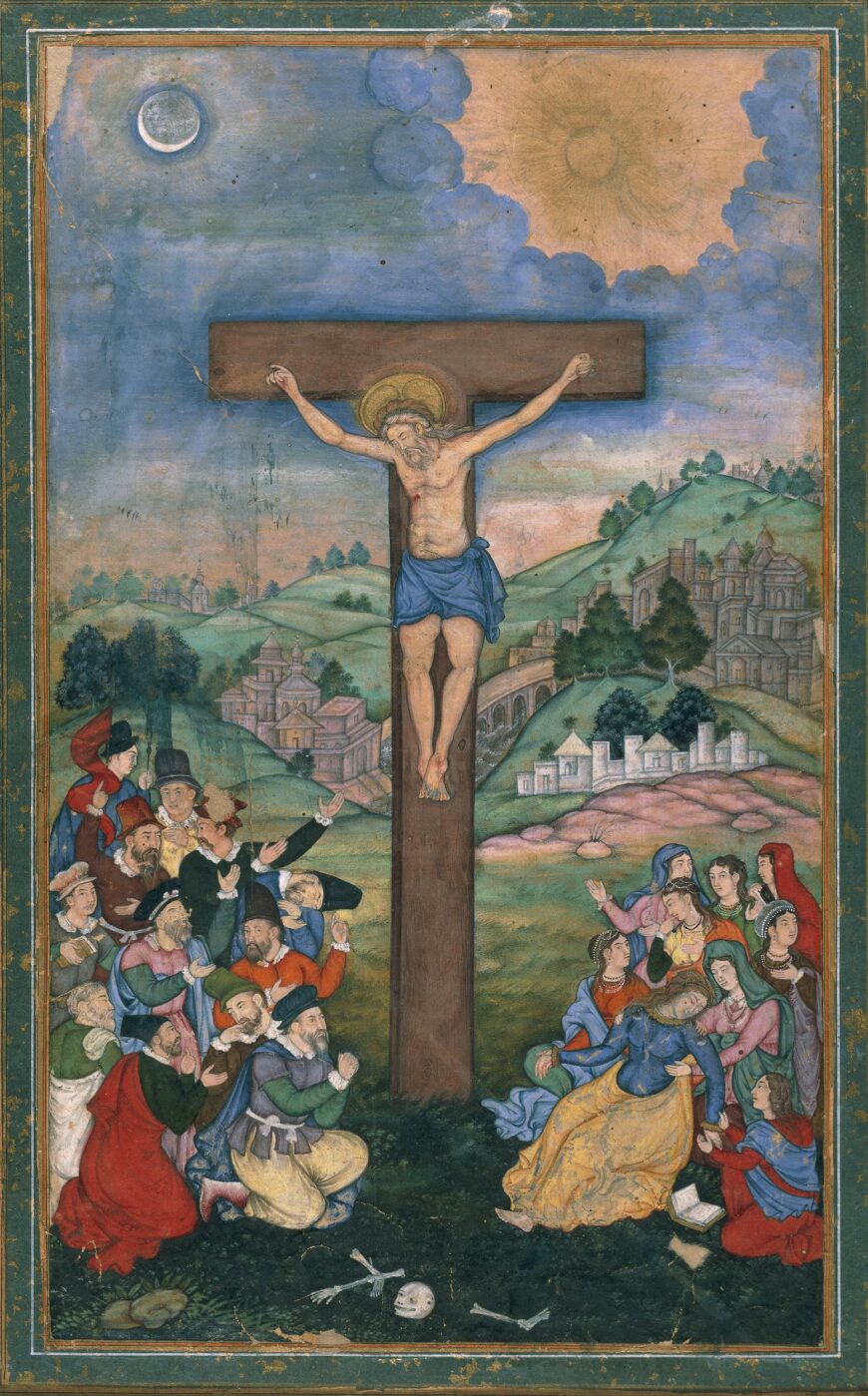

Attributed to Kesu Das, Crucifixion scene, c. 1590, ink, opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 29.3 x 17.7 cm (© The Trustees of The British Museum, London)

Depicting affinities between Christianity and Islam

Another painting, attributed to Kesu Das, also depicts Christ’s Deposition. Kesu Das worked in the ateliers of Akbar and Jahangir—it is not surprising that he was engaging with Christian themes and producing paintings such as this one for his patron. Believed to have been made in 1590, it is most likely based on Flemish religious prints. With the cross bifurcating the composition, we see an almost symmetrical grouping of people seemingly divided by gender—the Virgin swooning in a dead faint, as the women of Jerusalem bear her weight, on one side, and on the other side, a kneeling Saint John, with a derisive crowd behind him. The costumes of the men bear resemblance to contemporary fashions of the time and are visually similar to those worn by European visitors to the Mughal courts.

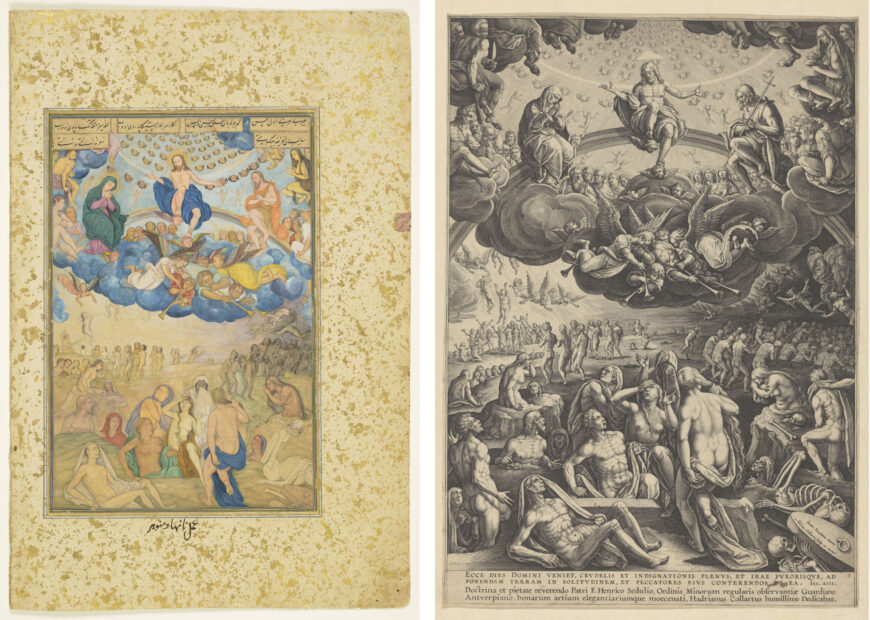

Left: Nanha and Manohar, The Day of Judgement, c. 1605–10, watercolor and gold paint on paper, 22.4 x 14.8 cm (The Royal Collection Trust, London); right: Adriaen Collaert after Jan van der Straet, The Last Judgement, c. 1580, engraving, 41.9 x 29.6 cm (Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels)

Sometimes, painters focused on affinities between Christianity and Islam—both Abrahamic religions—to create depictions that expounded upon religious concepts common to both. One example that stands out is The Day of Judgement, painted by Nanha and Manohar in c. 1605–10. Both artists were employed in the ateliers of Akbar, Jahangir, and Jahangir’s son and successor, Shah Jahan. This particular painting is a reinterpretation of a Flemish engraving from c. 1580 depicting the Last Judgment by Adriaen Collaert, after Jan van der Straet. Both the Flemish original and the Mughal version depict Jesus sitting on a rainbow looking down upon the believers and non-believers, preparing to cast judgment.

Here, we see how Nanha and Manohar make revisions to the original by drawing from the tradition of Mughal miniature painting that they were trained in. They have reduced the number of figures, rendering them in a soft, rounded form compared to the muscled, anatomical figures in the Collaert engraving. They also deploy the use of color to distinguish between the saved and the damned—bright colors for the believers and muted shades for the non-believers.

Left: Unidentified artist, The Madonna and Child, after Durer, early 17th century, watercolor on paper, 12.0 x 7.1 cm (The Royal Collection Trust, London); right: Albrecht Dürer, Madonna by the Tree, c. 1513, engraving, 11.7 x 7.4 cm (The Royal Collection Trust, London)

Mother Mary as an exemplary pious woman

The mughal painting of the Madonna and Child mirrors the composition of the Madonna by the Tree, by the German artist Albrecht Dürer. The Mughal painting retains several elements from the Dürer, such as the use of aerial perspective, the voluminous folds of Mary’s dress and the way in which she lifts the Christ child toward her face. However, the accompanying verse comes from the Quran, rather than the Bible:

And also We made the son of Mary and his mother a sign to mankind, and gave them a shelter on a peaceful hillside watered by a fresh spring. Quran 23:50

Attributed to Manohar or Basawan, Mother and Child with a White Cat, c. 1598, opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 21.7 x 13.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Not all works mirrored Christian compositions, but nonetheless drew inspiration from them. Consider this 1598 miniature painting attributed to either Basawan or Manohar depicting a light-skinned woman reclining on a carpet while nursing an infant, and resembling the images of Mary and Christ, were it not for slight differences that set it apart. In Christian depictions, the Madonna sits upright, cradling the baby in her arms and only her nursing breast is exposed while her eyes are turned towards the baby in a maternal gaze. In the Mughal version, both breasts are uncovered and her head is turned away from the baby, with a distant gaze and lack of emotion as she idly supports him with one hand. Here, the artist created their own interpretation of Mary and Christ iconography that combines both Christian and Mughal styles into a unique hybrid composition.

Abiding influences on Mughal art

Mughal artists were predominantly working from illustrated Bibles, prints, and images copied from one another. At the same time, they were not directly copying the engravings but imbuing them with their own stylistic conventions and adapting them to suit their own cultural and religious context.

In this article, we have mostly looked at examples of images made after European engravings and paintings, but it is worth noting that Mughal ateliers would adopt European iconographies—such as putti, cherubs, and halos—in paintings depicting secular subjects such as portraits of their rulers as well. Apart from the symbols and themes of these paintings, they also absorbed European painterly conventions such as the use of chiaroscuro and linear perspective.

The creation and circulation of images on Christian subjects and the use of iconography with biblical connotations in Mughal India perhaps had more to do with a fascination with a new visual language and its cosmopolitanism, rather than a belief in the religious faith. While the Jesuit missionaries may have hoped to evangelize the Mughal elite, their presence is perhaps most visible today through the Christian imagery that proliferated the paintings produced in Mughal ateliers.

Additional resources

Read more about the Mughal painting tradition

Collaboration, Invention and Artistic Development: The Kitabkhanas of Mughal South Asia

European Cherubs and Hindu Gods: A Portrait of Emperor Jahangir

What Rembrandt Learned from Mughal Miniatures

Collecting Chinese Porcelains in the Persianate World

Drawing from articles on The MAP Academy