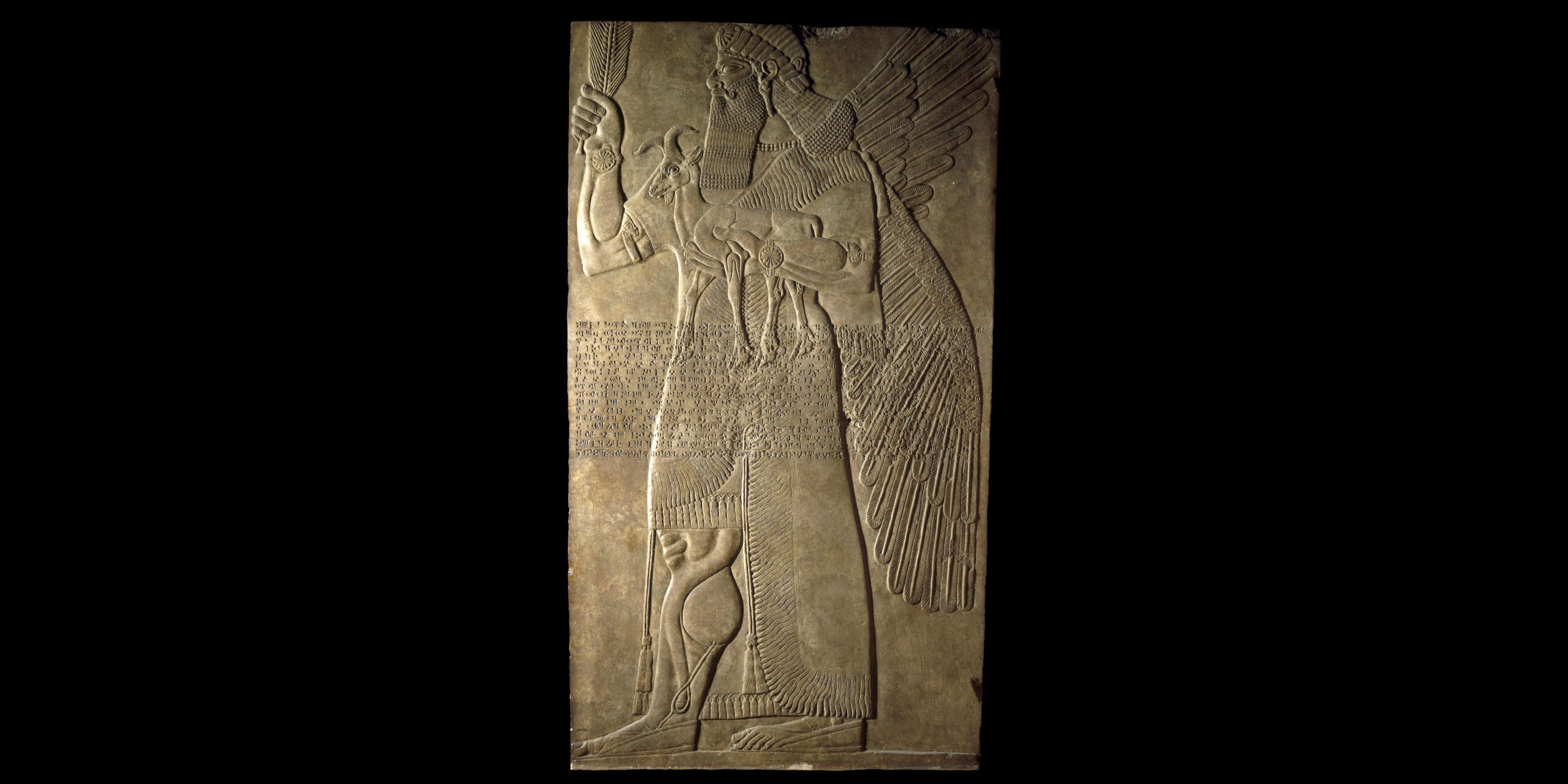

One of a pair which guarded an entrance into the private apartments of Ashurnasirpal II. The figure of a man with wings may be the supernatural creature called an apkallu in cuneiform texts. He wears a tasselled kilt and a fringed and embroidered robe. His curled moustache, long hair and beard are typical of figures of this date. Across the body runs Ashurnasirpal’s “Standard Inscription,” which records some of the king’s titles. Protective Spirit Relief from the North-West Palace of Ashurnasirpal II, 883–859 B.C.E., Neo-Assyrian, alabaster, 224 x 127 x 12 cm (extant), Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), northern Iraq © Trustees of the British Museum.

Leveraging their enormous wealth, the Assyrians built great temples and palaces full of art, all paid for by conquest. Although Assyrian civilization, centred in the fertile Tigris valley of northern Iraq, can be traced back to at least the third millennium B.C.E., some of its most spectacular remains date to the first millennium B.C.E. when Assyria dominated the Middle East.

Ashurnasirpal II

The Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II established Nimrud as his capital. Many of the principal rooms and courtyards of his palace were decorated with gypsum slabs carved in relief with images of the king as high priest and as victorious hunter and warrior. Many of these are displayed in the British Museum.

Ashurnasirpal II, whose name (Ashur-nasir-apli) means, “the god Ashur is the protector of the heir,” came to the Assyrian throne in 883 B.C.E. He was one of a line of energetic kings whose campaigns brought Assyria great wealth and established it as one of the Near East’s major powers.

This rare example of an Assyrian statue in the round was placed in the Temple of Ishtar Sharrat-niphi to remind the goddess Ishtar of the king’s piety. Ashurnasirpal holds a sickle in his right hand, of a kind which gods are sometimes depicted using to fight monsters. The mace in his left hand shows his authority as vice-regent of the supreme god Ashur. The carved cuneiform inscription across his chest proclaims the king’s titles and genealogy, and mentions his expedition westward to the Mediterranean Sea. Statue of Ashurnasirpal II, Neo-Assyrian, 883–859 B.C.E., from Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), northern Iraq, magnesite, 113 x 32 x 15 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Ashurnasirpal mounted at least fourteen military campaigns, many of which were to the north and east of Assyria. Local rulers sent the king rich presents and resources flowed into the country. This wealth was use to undertake impressive building campaigns in a new capital city created at Kalhu (modern Nimrud). Here, a citadel mound was constructed and crowned with temples and the so-called North-West Palace. Military successes led to further campaigns, this time to the west, and close links were established with states in the northern Levant. Fortresses were established on the rivers Tigris and Euphrates and staffed with garrisons.

By the time Ashurnasirpal died in 859 B.C.E., Assyria had recovered much of the territory that it had lost around 1100 B.C.E. as a result of the economic and political problems at the end of the Middle Assyrian period.

Part of a series which decorated the walls of a room in the palace of King Sennacherib (reigned 704–681 B.C.E.). The Assyrian soldiers continue the attack on Lachish. They carry away a throne, a chariot and other goods from the palace of the governor of the city. In front and below them some of the people of Lachish, carrying what goods they can salvage, move through a rocky landscape studded with vines, fig and perhaps olive trees. Sennacherib records that as a result of the whole campaign he deported 200,150 people. This was standard Assyrian policy, and was adopted by the Babylonians, the next ruling empire. The Siege and Capture of the City of Lachish in 701 B.C.E., panel 8–9, South-West Palace of Sennacherib, Nineveh, northern Iraq, Neo-Assyrian, c. 700–681 B.C.E., alabaster, 183 x 193 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Relief panels

Later kings continued to embellish Nimrud, including Ashurnasirpal II’s son, Shalmaneser III who erected the Black Obelisk depicting the presentation of tribute from Israel.

During the eighth and seventh centuries B.C.E. Assyrian kings conquered the region from the Persian Gulf to the borders of Egypt. The most ambitious building of this period was the palace of king Sennacherib at Nineveh. The reliefs from Nineveh in the British Museum include a depiction of the siege and capture of Lachish in Judah.

Part of a series of wall panels that showed a royal hunt. Struck by one of the king’s arrows, blood gushes from the lion’s mouth. There was a very long tradition of royal lion hunts in Mesopotamia, with similar scenes known from the late fourth millennium B.C.E. The Dying Lion, panel from the North Palace of Ashurbanipal, c. 645 B.C.E., Neo-Assyrian, alabaster, 16.5 x 30 cm, Nineveh, northern Iraq (British Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The finest carvings, however, are the famous lion hunt reliefs from the North Palace at Nineveh belonging to Ashurbanipal. The scenes were originally picked out with paint, which occasionally survives, and work like modern comic books, starting the story at one end and following it along the walls to the conclusion.

The Assyrians used a form of gypsum for the reliefs and carved it using iron and copper tools. The stone is easily eroded when exposed to wind and rain and when it was used outside, the reliefs are presumed to have been protected by varnish or paint. It is possible that this form of decoration was adopted by Assyrian kings following their campaigns to the west, where stone reliefs were used in Neo-Hittite cities like Carchemish. The Assyrian reliefs were part of a wider decorative scheme which also included wall paintings and glazed bricks.

The reliefs were first used extensively by king Ashurnasirpal II at Kalhu (Nimrud). This tradition was maintained in the royal buildings in the later capital cities of Khorsabad and Nineveh.

© Trustees of the British Museum