Thus begins the Preamble to the United States Constitution. And though this phrase be only three words, it is a complicated and ever-shifting expression. Indeed, who are “We the People” (today) and who have “We the People” been (over the past millennium)?

The close study of art can do much to answer this question, but one must proceed with extreme caution. Traditionally, the study of the art made in North America has largely involved the examination of painting and sculpture commissioned by the only group affluent enough to pay for such works: wealthy white men. The study of eighteenth-century art from the American Colonies is an excellent case in point. To look only at the artistic record, one might assume North America was predominantly populated by wealthy, well-dressed men of European heritage. If we broaden the lens of our examination—that is, if we look at art that extends beyond the painting and sculpture that was restricted to the elite—we see the ways the artistic record is filled with works from a panoply of peoples: those who were native to North America, and from peoples from both sides of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. These works have much to say about the shifting nature of national identity.

Mississippian culture

Gorget, c. 1250-1350, probably Middle Mississippian Tradition, whelk shell, 10 x 2 cm (National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, 18/853)

The Mississippian gorget (c. 1300 C.E.) is an excellent point of departure. A gorget is an ornament meant to be worn around the neck. This small object, carved out of shell likely brought from the Gulf of Mexico, was discovered at the end of the nineteenth century by an amateur archaeologist in a burial site in what is now north-central Tennessee. It is an object that speaks to the civilization, world views, and identity of the culture that made it, and those cultures with which it was in close contact.

The body of the intricately incised figure has been contorted to fit within the constraints of the round shape. The figure’s right knee is raised in front of him, while his left knee is similarly bent behind him, as if to suggest he is running. He holds a mace—a kind of weapon—in his left hand, while in his right he holds a decapitated human head. The fork-shaped form around his eye suggests the markings of a peregrine falcon, an element commonly seen in similar gorgets. He displays beads, both on his necklace and around his legs, and he also wears an elaborate headdress and decorated loincloth around his waist. The iconography of this object suggests the figure is Morning Star—who astronomically corresponds with Venus—a hero figure, who, with his twin brother, retrieved his father’s remains from the underworld. That similar figures have been found all over the large Mississippi Valley—and in a variety of media—tells us important things about pre-Columbian cultures in North America.

To begin an examination of this object, we need to displace some (likely) preconceived notions about pre-Columbian cultures in North America. When we speak of groups of Native Americans, we sometimes use the archaic term “tribes,” a word that seems to suggest a sense of isolation and separation. Moreover, when we think of the date of this object—it was made about 700 years ago—we might believe that the Mississippi Valley was an untamed wilderness, devoid of hamlets or towns. In fact, neither of these notions are necessarily true. As the Spanish conquistador Hernando de Sota observed between 1539-42, North America was filled with cities of various sizes. For example, the original Mississippian town, Cahokia, had a population of around 30,000 early in the second millennium, a size that was roughly equal to that of London at the same time. Clearly, any city of this size was multi-ethnic in nature and contained groups of different “tribes.” It also must have had contact with communities far beyond its own borders. Indeed, the Mississippian gorget is not an object about a single “tribe” that roamed the North American wilderness. Instead, it is a work that eloquently speaks about the ways in which different cultures lived in complex civilizations with firmly established belief systems before the first Europeans arrived.

Fashioning diplomacy: an Anishinaabe outfit

Anishinaabe outfit, c. 1790, collected by Lieutenant Andrew Foster, Fort Michilimackinac (British), Michigan, Birchbark, cotton, linen, wool, feathers, silk, silver brooches, porcupine quills, horsehair, hide, sinew; the moccasins were likely made by the Huron–Wendat people (National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution)

It would be inaccurate, of course, to assume that these disparate groups of Native Americans shunned contact with Europeans once they began to settle North America, and there is a perception that these two groups, from different sides of the Atlantic Ocean, were in constant conflict. In fact, these two groups often peacefully coexisted, deriving at least some mutual benefit. One might even suggest that in certain cases friendships formed. And like friendships today, these relationships centuries ago might prompt gift exchanges. The Anishinaabe outfit from the National Museum of the American Indian is one such gift. But this is no simple token of friendship. Instead, it is a powerful and forceful testament to trans-world mercantilism and trade, and the complex diplomatic relationships between world powers.

At first glance one might assume that this Native American outfit was intended for a Native American wearer. Instead, it was a gift to Andrew Foster, a lieutenant in the British army who served in the Great Lakes area—in what is now Michigan—around the year 1790. The end of the eighteenth century was a complicated time in the history of the United States. The Treaty of Paris, signed on 3 September 1783, officially ended the American Revolutionary War. Moreover, New Hampshire ratified the Constitution in June 1788, and the government of the United States formally began less than a year later on 4 March 1789. In an attempt to protect their North American interests, Great Britain searched out diplomatic relationships with various Native American groups in the Great Lakes area to buffer the approach of the ever-growing United States that was already eyeing westward expansion.

Clearly, about the time this extravagant outfit was made—and presented to a British army officer—the United States was very much attempting to figure out its place in the world, to say nothing of its place in North America. Six years after the close of the War of American Independence, the British army was still fully entrenched in the Great Lakes area and actively engaged in trade and diplomatic relationships with the Anishinaabe peoples who lived there. Although we are looking only at an Anishinaabe outfit given to a British officer, we can easily imagine British tokens of friendship being given to the leadership of the Anishinaabe peoples, too.

Anishinaabe outfit (detail), c. 1790, collected by Lieutenant Andrew Foster, Fort Michilimackinac (British), Michigan, Birchbark, cotton, linen, wool, feathers, silk, silver brooches, porcupine quills, horsehair, hide, sinew; the moccasins were likely made by the Huron–Wendat people (National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution)

A close examination of these garments points to the ways in which the eighteenth century was a time of long-distance commerce and trade. Great Britain became one of the world’s foremost mercantile powers, so much so that after the conclusion of the Seven-Years’ War (also referred to as the French and Indian War), the Irish-born British Statesman George Macartney wrote that Great Britain had become “the vast empire on which the sun never sets.” A fine illustration of this point is the shirt. The cotton for this shirt was grown in India—a British territory at the end of the eighteenth century—and then exported to Great Britain where the cloth was milled and manufactured into the cloth from which the shirt was made. The cut of the garment and the floral decoration were intended to appeal to a Native American audience. In short, this cotton shirt has had a multi-continent life. The cotton was grown in India, made into a shirt in England, exported to North America, and then returned to Britain when Foster returned home.

Other elements—such as the glass beads that decorate the necklace—are European made but designed to look as if they were manufactured in North America. These Venetian glass beads have been made to resemble wampum, a material Native Americans traditionally made from shells. Still other elements suggest trade between different groups of Native Americans. For example, the intricately decorated deerskin moccasins are not of Anishinaabe origin, but were instead made by women of the Huron-Wendat Nation and subsequently traded with Anishinaabe peoples. Like the Mississippian Gorget, Andrew Foster’s outfit eloquently speaks to intertribal commerce, exchange, and cooperation.

Wilderness, settlement, and American identity

If these first two works of art—the Mississippian Gorget and the Anishinaabe outfit—involve Native Americans both before and after the arrival of European settlers, Thomas Cole’s The Hunter’s Return (1845) is very much about that act of settlement by those Europeans. Although born in England, Cole moved to the United States when a teenager and is most well-known today for his landscapes that depict the Hudson River Valley of New York. In this autumnal landscape, the inclusion of the human figures and their domicile points to the westward expansion of the United States during the middle of the nineteenth century.

It is unlikely that Cole depicts a specific location in The Hunters Return. A log cabin—complete with smoke billowing from the chimney—can be observed on the right side of the composition, and a small garden is located just to its left. We see seven figures: the hunters of the title include the two men on the left side of the composition carrying the recently killed stag, and the young boy carrying the rifle over his shoulder who walks along the path towards the log cabin. Those who stayed behind include the two adult women (one of whom holds up an infant), and another young boy who embraces a dog, one that presumably was out with the hunting party. This multi-generational family suggests that they have lived here for a while, and the presence of a permanent structure such as a log cabin indicates that they will remain for some time to come, too.

Manifest Destiny

One can easily imagine what this scene may have looked like fifty years before Cole painted it. There would have been no log cabin, there would have been no human figures—and if they were there, they would not have been of European descent—and there would have been no felled trees or tree stumps to show the evidence of the saw (as we see in the lower right corner of the painting and between the garden and the log cabin). But by the middle third of the nineteenth century, there was an underlying notion in the United States that God placed Europeans in North America in order to settle the land and make it useful. No writer more forcefully expressed this than did John L. O’Sullivan, who in the July-August 1845 issue of the Democratic Review wrote that it was “our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.”

It is interesting to note that the first use of this term—Manifest Destiny, which would in time acquire Proper Noun status—was in 1845, the very year Cole completed The Hunters Return. Thus, Cole’s painting is not merely a composition about several hunters returning to their homestead after a successful hunt. Instead, it is a visual declaration of the political ideology of the process of (and results of) Manifest Destiny.

The middle of the nineteenth century in the United States was not only about westward expansion, it was also troubled by the brewing social, economic, and political turmoil growing between the North and the South in the ever-expanding country. The use of the first-person “our” in the O’Sullivan’s phrase “our manifest destiny” is as ambiguous as the first-person “we” in the “We the People” opening of the United States Constitution. It was clear by the middle of the nineteenth century that the “we” of “We the People” was restricted to the (white) people of European descent, not the Native Americans who predated European settlers by millennia or the African-Americans who had been enslaved here for generations.

Representing freedom during the Civil War

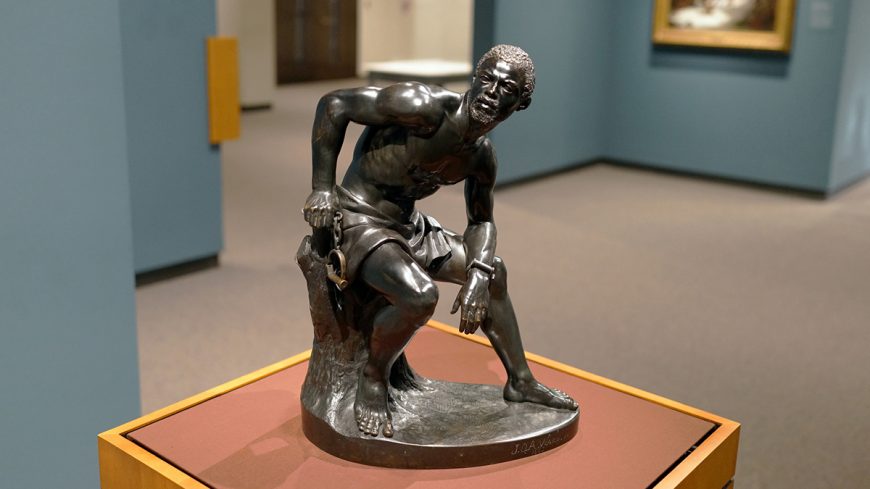

John Quincy Adams Ward, The Freedman, 1863, bronze (Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas)

The artist John Quincy Adams Ward cast The Freedman in 1863 during the middle of the American Civil War (1861-65). This creation date is important, for this object has strong ties to Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

The Emancipation Proclamation

On 22 September 1862, Lincoln issued a warning that he would free every slave in the states that did not end their rebellion against the Union. This was in strident opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 that stipulated that all slaves who escaped to free states must be returned to their captors, and the Dred Scott vs. Sandford decision of 1857 which stated that slaves were not citizens but instead only constitutionally protected property of their masters.

When the Civil War was still in full swing on 1 January 1863—and no slave state had withdrawn from the Confederacy and rejoined the Union—Lincoln issued the formal Emancipation Proclamation. In it, Lincoln wrote, “And by the virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of states, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.”

What Ward has so elegantly cast is the tangible and human result of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. An idealized and nude-to-the-waist African American male sits atop a tree stump, looking to his right with a sense of intense concentration on his face. His left forearm rests upon his left knee, and we can clearly see a manacle still in place around his left wrist. In contrast, he holds in his right hand the links to a manacle that once bound his two hands together. The juxtaposition of these two manacles—one still attached to the wrist, the other recently removed—suggests the ways in which his freedom has also not yet been fully accomplished.

While the Emancipation Proclamation may have freed this man, it hardly gave him freedom. It was not until the ratification of the 13th Amendment on 6 December 1865 that the practice of slavery was formerly abolished in the United States. But although the 13th Amendment only ended slavery, it did not necessarily provide citizenship, something that was only accomplished in July 1868 when the ratification of the 14th Amendment provided citizenship to all born in the United States. But even still, this was not the end of the road. For there are citizens, and there are citizens who can vote. And it was not until February 1870 when the ratified 15th Amendment—“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridge by the United States or by any State on the account of race, color, ore previous condition of servitude”—provided male African-Americans with full enfranchisement (at least in theory). And it was not until the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920 that women of any ethnicity were allowed the right to vote.

“Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free”

Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi (sculptor), Gustave Eiffel (interior structure), Richard Morris Hunt (base), Statue of Liberty, begun 1875, dedicated 1886, copper exterior, 151 feet 1 inch / 46 m high (statue), New York Harbor

One of the most recognizable works of art in the history of the United States is the Statue of Liberty. Although it was formally dedicated on 28 October 1886, a poem—written three years earlier by Emma Lazarus—was engraved onto a bronze plaque and placed inside the lower level of the statue’s pedestal in 1903. It reads, in part:

From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”Emma Lazarus, from The New Colossus, 1883

By 1903, Ellis Island was the busiest immigration inspection station through which aspiring citizens-to-be could enter the United States. Of course, immigration was not a new thing—the United States has always been a country populated by immigrants and the descendants of those immigrants—but immigration into the United States during the decades surrounding the turn of the twentieth century was particularly robust. It was during this time when the tired, the poor, the huddled masses yearning to breathe free most flocked to the United States. The Statue of Liberty stood tall to welcome them to their American Dream.

The Johnson-Reed Act

Then, as now, the topic of immigration was a complicated political topic. For example, the Immigration Act of 1924—sometimes called the Johnson-Reed Act—was passed to restrict the flow of potential immigrants from targeted parts of Europe. In an attempt to ensure that “America must remain American,” this act proposed an annual limit to the number of immigrants from each country to 2% of the number of people already living in the United States from that country. For those countries with a high immigration population already living in the United States—nations such as England and Germany—this act would have had little real practical effect (two percent of an enormous number is still a big number). For other countries—such as predominantly Catholic Italy, and those in Eastern Europe with a large Jewish population—this law severely restricted who could pursue the American Dream. At its core, the Johnson-Reed Act was an attempt to manipulate and control what future Americans would look like and what Americans believed (their religious faith).

Strange Worlds, immigrant experience in the early 20th century

Todros Geller painted Strange Worlds in 1928, just four years after the passage of the Johnson-Reed Act. Geller was an immigrant himself, having fled the pogroms (organized massacres of the Jews in Eastern Europe) in Ukraine, in 1906. He settled in Montreal, and then moved to the United States in 1918 and studied at the Art Institute of Chicago. This city had been a hotbed of immigration from Eastern Europe for decades. One only need recall Jurgis Rudkus, the Lithuanian immigrant in Upton Sinclair’s novel, The Jungle (1906) to be reminded of the incredible melting pot Chicago had become.

In Strange Worlds, Geller gives us a visual representation of what the immigrant experience might have been for those living in Chicago during the early decades of the twentieth century, and the plurality of that title—Strange Worlds, not Strange World—speaks to the difficulty many had in coming to America. A solitary elderly man stares out at us from the left foreground, a tense, distant look on his face. With his dark hat and nondescript clothing, it is clear that this figure is not intended to be a portrait of a specific person. Instead, it is a representation of a type; in this instance, the type is that of the Eastern European immigrant. The compressed foreground is filled by the figure, a diagonal staircase leading upwards to one of Chicago’s elevated trains (a track of which can be seen in the distance, in the upper right corner), and a collage of newspapers. These two elements—the L and newspapers—would hardly have seemed strange to anyone living in Chicago at the time. But the figure’s wearied look and his own isolation makes clear that he is a foreigner in a foreign land.

If the foreground—the man’s own space—is static, and, one might say, comparatively traditional, then the background is much more dynamic and modern. The human figures and the landscape have been painted with a kind of kinetic energy that vibrates through the background. And this tension—between the man’s own space and that which surrounds him—was part of the immigrant experience for millions of new Americans. America was strange to them, and, as important, they were strange to (the) Americans (already here). Even if this man were granted citizenship and the right to vote, one gets the idea that he is not yet a part of “We the People.”

Nari Ward, We the People (black version), 2015, shoelaces, 8 × 27 feet (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas)

E Pluribus Unum

In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson wrote, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Who qualified for these unalienable rights has shifted and changed over time, just as who has been included in “We the People” has changed, too. These changes and additions are part of our national identity, one that is also in a state of dynamic flux. But even though that identity may have changed, the idea of E Pluribus Unum—out of many, one—has remained constant in the United (an adjective that implies singularity) States (a plural noun).