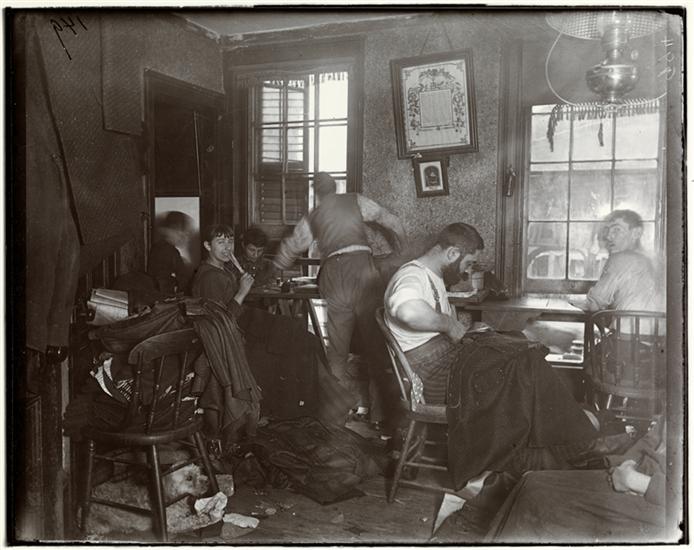

Jacob August Riis, “Knee-pants” at forty five cents a dozen—A Ludlow Street Sweater’s Shop, c. 1890, 7 x 6″, from How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, 1890 (The Museum of the City of New York)

The slums of New York

Jacob Riis documented the slums of New York, what he deemed the world of the “other half,” teeming with immigrants, disease, and abuse. A police reporter and social reformer, Riis became intimately familiar with the perils of tenement living and sought to draw attention to the horrendous conditions. Between 1888 and 1892, he photographed the streets, people, and tenement apartments he encountered, using the vivid black and white slides to accompany his lectures and influential text, How the Other Half Lives, published in 1890 by Scribner’s. His powerful images brought public attention to urban conditions, helping to propel a national debate over what American working and living conditions should be.

Jacob August Riis, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, 1890

A Danish immigrant, Riis arrived in America in 1870 at the age of 21, heartbroken from the rejection of his marriage proposal to Elisabeth Gjørtz. Riis initially struggled to get by, working as a carpenter and at various odd jobs before gaining a footing in journalism. In 1877 he became a police reporter for The New York Tribune, assigned to the beat of New York City’s Lower East Side. Riis believed his personal struggle as an immigrant who “reached New York with just one cent in my pocket”¹ shaped his involvement in reform efforts to alleviate the suffering he witnessed.

As a police reporter, Riis had unique access to the city’s slums. In the evenings, he would accompany law enforcement and members of the health department on raids of the tenements, witnessing the atrocities people suffered firsthand. Riis tried to convey the horrors to readers, but struggled to articulate the enormity of the problems through his writings. Impressed by the newly invented flash photography technique he read about, Riis began to experiment with the medium in 1888, believing that pictures would have the power to expose the tenement-house problem in a way that his textual reporting could not do alone. Indeed, the images he captured would shock the conscience of Americans.

Jacob August Riis, The Mulberry Bend, c. 1890, 7 x 6″, from How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, 1890 (The Museum of the City of New York)

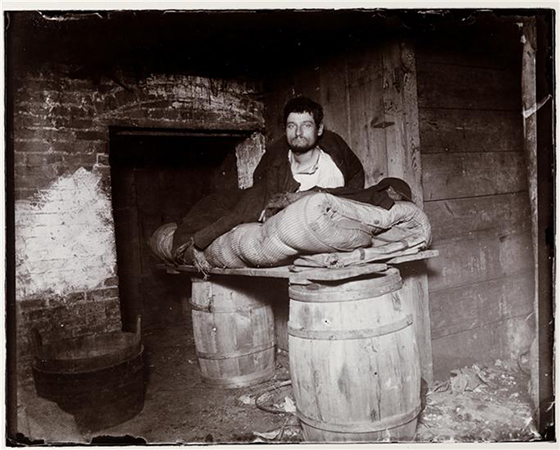

Midnight rounds

At first Riis engaged the services of a photographer who would accompany him as he made his midnight rounds with the police, but ultimately dissatisfied with this arrangement, Riis purchased a box camera and learned to use it. The flash technique used a combination of explosives to achieve the light necessary to take pictures in the dark. The process was new and messy and Riis made adjustments as he went. First, he or his assistants would position the camera on a tripod and then they would ignite the mixture of magnesium flash-powder above the camera lens, causing an explosive noise, great smoke, and a blinding flash of light. Initially, Riis used a revolver to shoot cartridges containing the explosive magnesium flash-powder, but he soon discovered that showing up waving pistols set the wrong tone and substituted a frying pan for the gun, flashing the light on that instead. The process certainly terrified those in the vicinity and also proved dangerous. Riis reported setting two fires in places he visited and nearly blinding himself on one occasion.

Jacob August Riis, “A man atop a make-shift bed that consists of a plank across two barrels,” c. 1890, 7 x 6″, from How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, 1890 (The Museum of the City of New York)

Home and work

While it is unclear if Riis’ pictures were totally candid or posed, his agenda of using the stark images to persuade the middle and upper classes that reform was needed is well documented. A major theme of Riis’ images was the terrible conditions immigrants lived in. In the 1890s, tenement apartments served as both homes and as garment factories. “Knee-Pants at Forty-Five Cents a Dozen—A Ludlow Street Sweater’s Shop” depicts the intersection of home and work life that was typical. Note the number of people crowded together making knickers and consider their ages, gender, and role. Each worker would be paid by the piece produced and each had his/her own particular role to fill in the shop which was also a family’s home.

Detail, Jacob August Riis, “Knee-pants” at forty five cents a dozen—A Ludlow Street Sweater’s Shop, c. 1890, 7 x 6″, from How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, 1890 (The Museum of the City of New York)

While Riis did not record the names of the people he photographed, he organized his book into ethnic sections, categorizing the images according to the racial and ethnic stereotypes of his age. In this regard, Riis has been criticized for both his bias and reducing those photographed to nameless victims. “Knee-Pants,” appears in the chapter Jewtown and one can assume that the individuals are part of the large wave of Eastern European Jewish migration that flooded New York at the turn of the twentieth century.

Detail of the “Table of Contents,” Jacob August Riis, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, 1914

They are likely conversing in Yiddish and share some type of familial or neighborly connection. Some of the workers depicted might have lived in a neighboring New York City apartment or next door back in the old country. Home life, family relations and business relations, are intertwined. Just as it is impossible to know the names of the people captured in Riis’ image, and what Riis actually thought of them, one also cannot know their own impressions of the workplace, or their hopes and day-to-day challenges.

Jacob August Riis, “12 year old boy at work pulling threads. Had sworn certificate he was 16—owned under cross-examination to being 12. His teeth corresponded with that age,” c. 1890, 7 x 6″, from How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, 1890 (The Museum of the City of New York)

The work performed in tenements like these throughout the Lower East Side made New York City the largest producer of clothing in the United States. Under the contracting system, the tenement shop would be responsible for assembling the garments, which made up the bulk of the work. By 1910, New York produced 70% of women’s clothing and 40% of men’s ready-made clothing. That meant that the knee-pants and garments made by the workers captured in this Ludlow Street sweatshop were shipped across the nation. Riis’ photographs helped make the sweatshop a subject of a national debate and the center of a struggle between workers, owners, consumers, politicians, and social reformers.

The Progressive Era

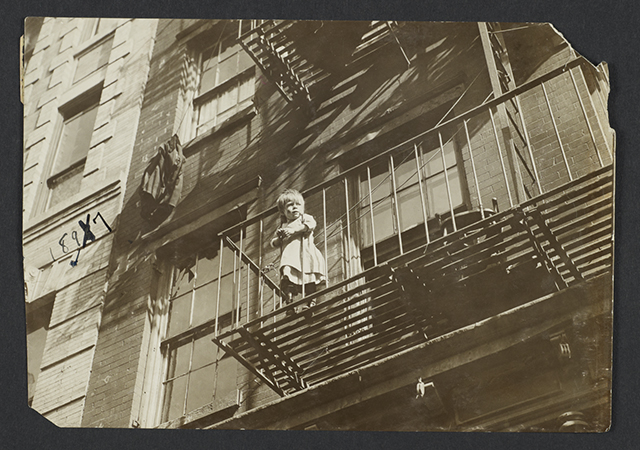

Riis’ photographs are part of a larger reform effort undertaken during the Progressive Era, that sought to address the problems of rapid industrialization and urbanization. Progressives worked under the premise that if one studies and documents a problem and proposes and tests solutions, difficulties can ultimately be solved, improving the welfare of society as a whole. Progressives like Riis, Lewis Hine, and Jessie Tarbox Beals pioneered the tradition of documentary photography, using the tool to record and publicize working and housing conditions and a renewed call for reform. These efforts ultimately led to government regulation and the passage of the 1901 Tenement House Law, which mandated new construction and sanitation regulations that improved the access to air, light, and water in all tenement buildings.

Jessie Tarbox Beals, Child on Fire Escape, c. 1918, for the New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor (Columbia University Libraries)

In the introduction to the How the Other Half Lives, Riis challenged his readers to confront societal ills, asking “What are you going to do about it? is the question of to-day.” It was a question of the past, but one that endures.

1. Jacob Riis, The Making of An American, 2: 18

Additional resources:

Jacob A. Riis Photographic collection, The Museum of the City of New York

Ginia Bellafante, Discussion on How the Other Half Lives, The New York Times

Texts by Jacob Riis online bartleby.com

“Jacob Riis and the Other Half” website by Lisa Xie

Bonnie Yochelson and Daniel Czitrom, Rediscovering Jacob Riis: Exposure Journalism and Photography in Turn-of-the-Century New York ( Chicago University Press, 2014).