Richard Caton Woodville, War News from Mexico, 1848, oil on canvas, 68.6 × 63.5 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas). Speakers: Dr. Mindy Besaw, curator, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, and Dr. Steven Zucker

[0:00] [music]

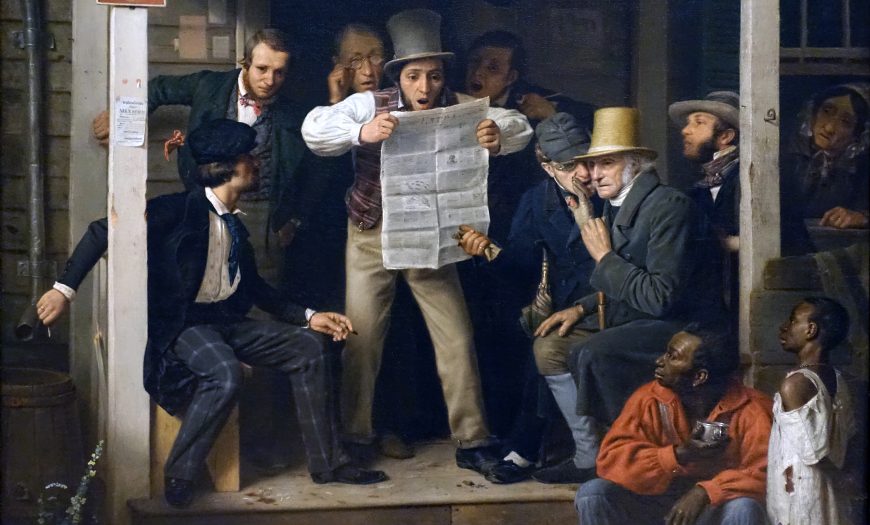

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re in the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, looking at a painting by Richard Woodville. This is “War News from Mexico.” The man at the center seems to be reading out loud the newspaper that he holds. What was being conveyed was the war between the young republic of the United States and Mexico, an even younger republic.

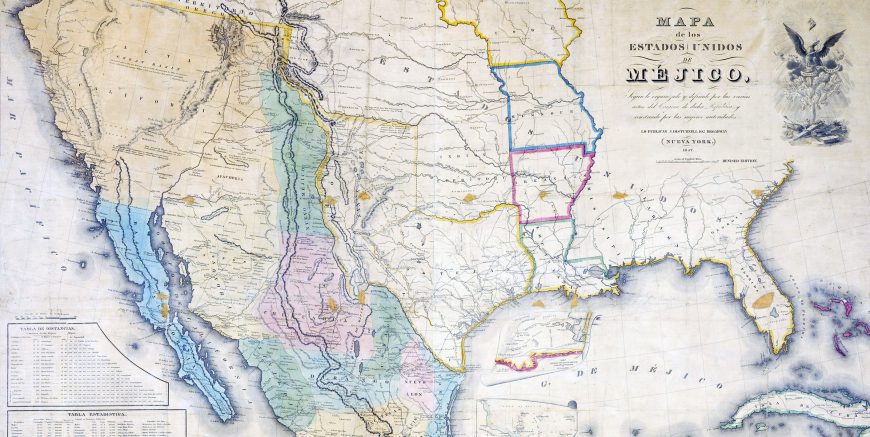

[0:24] Mexico had only gained its independence from Spain a couple of decades earlier. What would happen in 1848 is that the United States would successfully invade Mexico City, and would state terms for a treaty that would cede approximately half of Mexico to the United States, the states that we now know as California, Nevada, much of Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona.

Dr. Mindy Besaw: [0:46] Texas is maybe what started the whole thing. [It] was a dispute over the border between the United States and Mexico. It was very divisive conversation in newspapers.

Dr. Zucker: [0:59] Would those new territories become free states or would they become slave states? Until this point, there had been balance between those two kinds of states, and there was real concern that this would upset that balance.

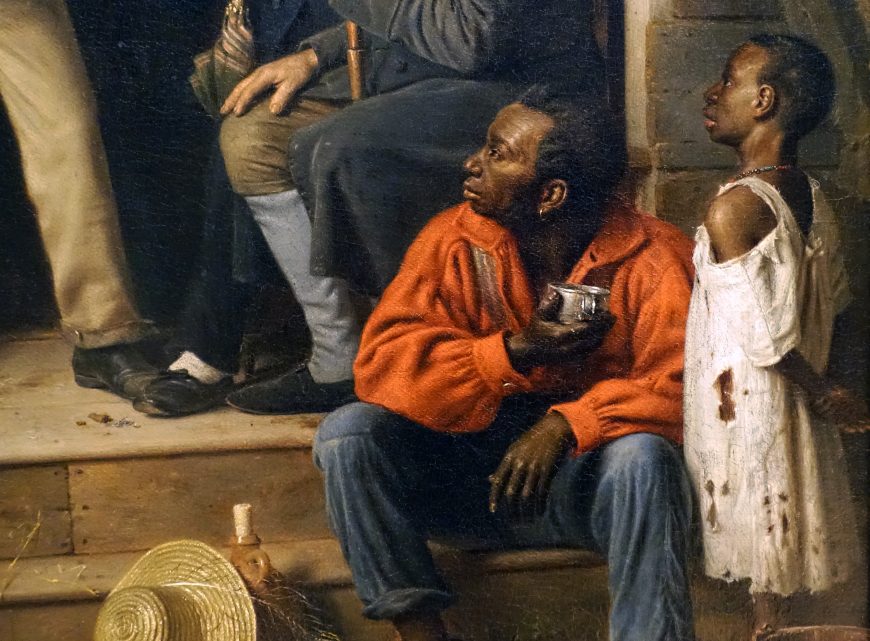

Dr. Besaw: [1:11] Even though Woodville is not necessarily telling us where he falls with this, he’s certainly showing that that was one of the central issues of this war by including the African American figures because they want to know what’s happening. Will slavery be expanded? Slavery was an issue much earlier than the actual outbreak of the Civil War.

Dr. Zucker: [1:33] The war with Mexico was forcing the issues that would eventually unleash the Civil War. Of course, the artist had no idea that the Civil War was coming, but that was only a little more than a decade off.

Dr. Besaw: [1:43] There are 11 figures. Most of them are white males standing or sitting on the portico of what we know to be the American Hotel. It’s also important to see who is not on the central platform.

[1:59] This is an illustration of a social hierarchy. White men in the center in protected space. Just to the right, a woman leaning out the window, craning her head as if to hear the news. She is relegated to that domestic sphere, the inside.

Dr. Zucker: [2:17] She’s impacted by what those men are reading, but she doesn’t have the vote. She is not a part of the political sphere. An African American sits on the bottom step. He’s lower, and so the hierarchy is made very clear. He’s also outside, but he’s no less interested.

[2:33] To me, it’s such a sympathetic father and child. The child wears rags filled with holes, and their poverty is made so clear. The colors of their clothing are red, white, and blue, the colors of the American flag.

Dr. Besaw: [2:46] So even if you divide this as if it’s a ladder, they’re truly at the very bottom, touching the ground, associated with labor rather than elevated onto the steps, but if you look closely, there’s a shabbiness. Woodville is meticulous in the details. Is this a New England porch? Is this something in the South? Something in the frontier?

[3:12] I think Woodville does give us details that might hint to a specific location, but then he makes it so general that it could be my town, it could be your town, it could be almost anyone’s town.

Dr. Zucker: [3:23] There is this sense that the artist wanted to convey a familiarity so that we felt we knew these people.

Dr. Besaw: [3:29] Woodville is painting for an American audience that is divided. By leaving things very general, like an American hotel, his audience in the North, his audience in the South, everyone would clamor for this image, and anyone could interpret it really how they wanted to.

Dr. Zucker: [3:49] In fact, this painting became tremendously popular because a print was made for it. As many as 14,000 copies ended up in American homes.

Dr. Besaw: [3:58] You would have Northerners, Southerners, Abolitionists, those that were for slavery — all of them snatching this up.

Dr. Zucker: [4:06] When we look at the painting now in the 21st century, I think we see it as quite old-fashioned, but in fact, this was a painting that was reflecting modernity. It was reflecting modern technologies. The newspaper was able to speed news across the continent at a rate that had never been possible before, in large part because of the invention of the telegraph.

[4:26] The very technology that reproduced the painting as a print that could then be distributed was another expression of the modern world, the growth of a middle class that could enjoy art, and one that was interested in its world and in its political agency.

Dr. Besaw: [4:41] You have the newspaper, which is this modern technology spreading the news, but yet one man is selecting what he wants to announce. We do have maybe two other men who are reading it over the shoulder, but then there’s even one more layer of interpretation for the — maybe that’s a clerk who’s been relaying the news to the old man.

[5:02] The old man is a reference back to the Revolutionary War. This is an old veteran. 1848 is right at the time when Manifest Destiny was so firmly believed, that it seemed to entitle the United States to land.

Dr. Zucker: [5:21] The president at this time was a man named Polk, and he was a firm believer that the United States should stretch from the east coast all the way to the west coast.

Dr. Besaw: [5:31] From sea to shining sea. That was truly the ideal of the time period. It didn’t matter that there were Indigenous people living there because it was as if it was our God-given right to take over the land, but that belief overlooked so much that was problematic.

Dr. Zucker: [5:51] Even within the frame of this painting, we see the central figures completely preoccupied by the news and each other. Nobody looking to the figures that are at the borders of this painting.

Dr. Besaw: [6:03] Looking at the sign, “American Hotel,” it’s very intentional that Woodville has cut the sign so that “American,” the word, is cut off. The head of the eagle is also severed. This may just be one more hint that something is amiss. These little hints that the artist is giving us to help us read and interpret this image.

[6:27] [music]

Richard Caton Woodville, War News from Mexico, 1848, oil on canvas, 68.6 × 63.5 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas)

A crowd gathered for the news

The young man in the center of a crowd in Richard Caton Woodville’s War News From Mexico (1848) holds open a newspaper with his elbows up, but the paper is low enough that we can see the astonished look on his face.

Map of Mexico, color-filled areas show Mexican territory in 1847. The yellow and green areas at the top left became part of the southwestern United States in 1848.

Volunteer Flyer (detail), Richard Caton Woodville, War News from Mexico, 1848, oil on canvas, 68.6 × 63.5 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas)

And the news itself? As the title indicates, this is a dispatch from the front of the Mexican-American War. United States troops entered Mexico City in 1848, bringing to an end a war that had begun in 1846 over a territorial dispute involving Texas. In the resulting Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico ceded half its territory to the United States, effectively concluding the U.S. program of westward expansion.

To convey the characteristics of a Western outpost, the men gathered in the painting are shown standing on the porch of a building typical of the kind erected in the American frontier during the rush for territories in the early decades of the nineteenth century. In fact, the building serves multiple functions: it is both an “American Hotel” and post office, as indicated on the signs. While the building emulates in wood the style of stone classical structures found in Philadelphia or New York City, the artist has taken great care with the details to remind the viewer this is on the frontier: the wood is worn, and underneath the “post office” sign is tacked a recruitment notice asking for “Volunteers for Mexico!”

A range of responses

Opinion on the war was divided and Woodville thus depicts a range of responses. An older man in Revolutionary-era clothing just to the right of the standing figure holding the newspaper, strains to hear as another repeats into his ear what is being read. One young man in the background is tossing his hat into the air; he clearly welcomes the news but the seated elder shows far less enthusiasm. His outdated clothing identifies him as part of the generation that fought the Revolutionary War but did not endorse the expansion embraced by the new Jacksonian-era democracy. And what of the inhabitants themselves of the former Spanish colonies in the southwest (Mexico had gained independence from Spain in 1821)? This could only be bad news; the surrendering of territory spelled the loss of cultural identity. A protestant, Anglo-American culture, pushing westward, acquiring new states for the Union, would seek to eradicate any vestiges of Hispanic-Catholic identity. Mexicans would wake up the day after the treaty was signed and find themselves second-class citizens in a new country.

Porch (detail), Richard Caton Woodville, War News from Mexico, 1848, oil on canvas, 68.6 × 63.5 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas)

Genre scenes

American genre-scene painters during this period typically strove to represent an array of social types in their rapidly modernizing nation, and Woodville’s painting is no exception (“genre” paintings depict scenes of everyday life). There were often humorous illustrations of class status or newly immigrant Americans in genre scene paintings but they also betrayed, in equal measure, social anxiety about a shifting demography in a new political environment. There are African-American figures in the painting but they are pushed to the border, outside the framing beams of the hotel’s portico—a seated man in a bright orange shirt and a child wearing a tattered white dress. They look on from the bottom right, at the foot of the steps, but their facial expressions seem to register only weariness or perhaps resignation. The question as to whether the new territories would be slave states or free ones was hotly debated—some saw the war as extending the institution of slavery—and Woodville nods to this larger political reality. There is also an elderly woman barely visible in the shadows; she leans out a window and looks in the direction of the group on the porch. These figures are not included within the immediate circle of white men—perhaps suggesting their less central position within society.

Man and child, lower right (detail), Richard Caton Woodville, War News from Mexico, 1848, oil on canvas, 68.6 × 63.5 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas)

Images of frontier life were popular in the years leading up to the Civil War and Woodville had great success depicting this kind of everyday subject matter. He specialized in domestic interiors—an important subset of this newly emergent category of genre-scene painting. This subject type was popular in Europe (particularly during the 17th century in the Dutch Republic), however it was a relatively new phenomenon in American art—reaching its height of popularity in the period that stretched from the 1830s through the Civil War of 1861-65. Genre scene paintings were aimed at a broadly expanded and increasingly literate middle-class whose tastes ran to familiar scenarios of everyday life, rather than the mythic or historical themes favored by the art academies (the Royal Academies of Europe and the National Academy in the United States). Genre-scene paintings were promoted by organizations like the American Art Union (AAU). The AAU was formed in 1839 to promote American artists and specifically to forge a uniquely American art. Once exhibited under the aegis of the AAU—Woodville’s War News From Mexico was exhibited in 1849 right after the war ended—paintings were then turned into engravings and sold to AAU members by subscription.

Woman in window (detail), Richard Caton Woodville, War News from Mexico, 1848, oil on canvas, 68.6 × 63.5 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas)

In contrast to the marginalized figures of the woman and the African Americans, the newspaper takes pride of place in this painting. The “penny presses,” as they were called, a relatively recent invention, were mass-produced commercial newspapers that emerged in the 1830s during a period of rapid industrialization and modernization. Unlike their more expensive, subscription-based counterparts, the penny presses (so named because they cost mere pennies) reached a broad swath of the American public. Not only was the Mexican-American War one of the very first to be photographed, it was also extensively broadcast through print—through the very type of paper depicted in the painting, with its top banner emblazoned with the words “EXTRA.” The newspaper, in fact, functioned as a powerful symbol of the power of the press to bring Americans together and the painting suggests the role of the paper in shaping public opinion.

Newspaper (detail), Richard Caton Woodville, War News from Mexico, 1848, oil on canvas, 68.6 × 63.5 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas)

Genre-scene paintings often conveyed a sense of immediacy and here War News From Mexico orients itself towards the viewer in such a way that one feels as if one has just stumbled upon the scene. Notice, for example, how the perspective is tilted to the right of the viewer; this has the effect of positioning us off to the left side as if we have just come around some imaginary corner and the American Hotel, its porch crowded with the town’s inhabitants, careens into view.

Manifest Destiny

Despite this seeming spontaneity, War News from Mexico is as carefully composed and even as moralizing as the staid history paintings and Neoclassical subjects favored by the academies. Though it was commonplace to view genre-scene paintings as “snapshots” of daily American life without larger purpose, this unfolding scene (meant to indicate some place on the frontier far removed from the military action, but close enough that it mattered), takes place against the backdrop of Manifest Destiny—the theory that drove and justified westward expansion.

The ideology of Manifest Destiny construes Anglo-Americans as God’s chosen people who—like the ancient Israelites of the Old Testament—are guided by God to their destiny. This was a subject often depicted in painting. For example, in Emmanuel Leutze’s mural for the west stairway of the U.S. Capitol, Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way, we see American pioneers and their covered wagons looking towards the sunset and the Pacific Ocean while one of the scenes in the lower right border (illustrated left) depicts Moses leading the Israelites through the desert.

Emanuel Leutze, Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way, 1862, stereochrome, 6.1 × 9.1 m (United States Capitol, Washington, D.C.)

Beginning with the American Revolution, this American “exceptionalism” (as it also came to be known), rationalized not only the acquisition of land all the way to the Pacific Ocean, but also the subjugation and removal of people from their land—the Indian Removal Act of 1830 that President Andrew Jackson signed into law strengthened the rapid acquisition of land that went hand in hand with expulsion and extermination.

Woodville makes no overt statement of his politics in War News from Mexico but his painting nevertheless encapsulates a larger history than the scale of this relatively small painting (it measures approximately 27 x 25 inches) would seem to allow. If War News from Mexico does, however ambiguously, extol the ideology of Manifest Destiny and the inevitability of America’s domination of a large part of the continent, it is an ironic fact of history that Woodville’s scenes of life in the American West were painted while he lived in Europe. Born in Baltimore, Woodville left for Europe as a young man to train in Düsseldorf, Germany, and remained abroad until his death in London at the age of 30.