Hiram S. Powers, The Greek Slave, 1866, marble, 166.4 x 48.9 x 47.6 cm (Brooklyn Museum) Speakers: Margarita Karasoulas, Assistant Curator of American Art, Brooklyn Museum and Beth Harris

They say Ideal beauty cannot enter

The house of anguish. On the threshold stands

An alien Image with enshackled hands,

Called the Greek Slave! as if the artist meant her

(That passionless perfection which he lent her,

Shadowed not darkened where the sill expands)

To so confront man’s crimes in different lands

With man’s ideal sense. Pierce to the centre,

Art’s fiery finger! and break up ere long

The serfdom of this world. Appeal, fair stone,

From God’s pure heights of beauty against man’s wrong!

Catch up in thy divine face, not alone

East griefs but west, and strike and shame the strong,

By thunders of white silence, overthrown.

— Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Poems, 1850

It is a rare work of art that could inspire the lyrical pen of a poetess as talented as Elizabeth Barrett Browning, but such was the universal acclaim of Hiram Powers’s The Greek Slave a mere five years after he first exhibited his statue in London. Powers, an American expatriate sculptor who had been living and working in Italy since 1837, was suddenly vaulted into the pantheon of great (American) sculptors, and drew favorable comparisons to Phidias and Michelangelo.

From Cincinnati to Florence

Hiram Powers, Martin van Buren, modeled 1836, carved 1840, marble, 54.3 x 61.2 x 34.2 cm (The White House)

And yet, for Powers—who turned 40 in 1845, when The Greek Slave was first exhibited—it had been a long journey from his hometown of Cincinnati, Ohio. Born in Woodstock, Vermont, Powers’ family moved near Cincinnati when he was 14 years old. At the death of his father, Powers moved into the city and began work, first as a superintendent of a reading room attached to a hotel, and later as a clerk at a general store. His introduction to the art-making world was a humble one. At the age of 17 he worked as an apprentice to a wooden clockmaker. Several years later—in 1826—Powers began to study with Frederick Eckstein, a local sculptor of some regional renown. In his studio, Powers learned to model the human face and figure, and how to create plaster casts.

These skills were put to great use at Joseph Dorfeulle’s Western Museum. While there, Powers created animatronic wax figures to occupy scenes taken from Dante’s Inferno. At the same time, Powers began to create portrait busts of his friends. These likenesses brought him to the attention of Nicholas Longworth, a local wine entrepreneur. Longworth paid for Powers to undertake two extended periods of study away from Ohio: first to New York City (1829) and then later to Washington, D.C. (1834).

It was this later trip to the nation’s capital that propelled Powers onward to the success he would later find with The Greek Slave. While there, he sculpted many Washingtonian elites, including current and former presidents—Andrew Jackson (1834), John Quincy Adams (1837), and Martin van Buren (1837)—as well as John Marshall (1835), the second chief justice of the United States Supreme Court. These successes prompted Powers to follow the lead of another American neoclassical sculptor, Horatio Greenough, and depart his native shores for Italy. Greenough had already been in Italy since 1828; if Powers hoped to emulate the work of Michelangelo and Bernini, then Florence was just the place to do it.

An American Venus

And so, in 1837, Powers moved to Italy, never again to step upon American shores. Four years later, he was at work on The Greek Slave, the sculpture that has become his most recognized and celebrated work. Powers completed no less than six full-sized versions of this work between 1843 and 1866, and it secured his fame on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Indeed, had he made nothing else of note, this work alone would have vaulted Powers into the pantheon of American sculptors. The Greek Slave was both familiar and new, and exceedingly relevant for the audiences that first viewed it.

Hiram Powers, The Greek Slave, model 1841-43, carved 1846, Serravezza marble, 167.5 × 51.4 × 47 cm (National Gallery of Art); Aphrodite of Cnidos, torso: Roman copy, 2nd century C.E., restoration, 17th century, marble (Rome, Roman National Museum, Palazzo Altemps); Venus de’ Medici, 1st century B.C.E. (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

In it, Powers sculpted a nearly life-sized nude female. Posed in the High Classical contrapposto, the figure faces towards her left so that when her body is viewed frontally, her face appears in near-perfect profile. Her weight-bearing left leg counterbalances the straight right arm, which leads the eye downwards to the drapery-covered vertical support. In contrast, her bent left arm leads the eye across her unclothed body towards both her non-weight-bearing right leg and the chains that bind her two hands together. Indeed, much like the classical (ancient Greek and Roman) works that Powers based The Greek Slave on—Praxiteles’s Aphrodite of Knidos and the Medici Venus immediately come to mind—this gestural attempt to hide her nudity only forces the viewer to more directly address it.

The story of The Greek Slave

But who is this woman? Why is she nude? And what has caused her hands to be chained? In order to answer these questions—and, as importantly, justify Powers’s then scandalous use of female nudity—Powers himself wrote an explanatory text to accompany the exhibition of his work. In it, he explained that his figure is an enslaved Greek maiden who stands in a slave market during the time of the Greek War for Independence against Turkey (1821-32).

Hiram Powers, The Greek Slave (detail), model 1841-43, carved 1846, Serravezza marble, 167.5 × 51.4 × 47 cm (National Gallery of Art)

The Slave has been taken from one of the Greek Islands by the Turks, in the time of the Greek revolution….Her father and mother, and perhaps all her kindred, have been destroyed by her foes, and she alone preserved as a treasure too valuable to be thrown away. She is now among barbarian strangers…and she stands exposed to the gaze of the people she abhors, and awaits her fate with intense anxiety, tempered indeed by the support of her reliance upon the goodness of God. Gather all these afflictions together, and add to them the fortitude and resignation of a Christian, and no room will be left for shame.

Upon close inspection, one can see a small cross and locket carved on the support. The cross hints at her everlasting Christian faith, while the locket suggests far away love. Through these small details, Powers sets the stage for our reaction: a young Christian female has been abducted from her family, has been stripped bare by her captors, and now stands judged in the slave market. The pathos is palpable.

John Vanderlyn, Ariadne Asleep on the Island of Naxos, 1809-14, oil on canvas, 174 x 221 cm (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts)

That The Greek Slave is nude—and that this nudity was deemed acceptable and appropriate to the audiences who viewed it—is very much a part of this work’s history. Nineteenth-century American art does not overflow with examples of the female nude, and those artists who attempted to paint or sculpt such scandalous subjects were often disappointed by reactions to their work. John Vanderlyn’s 1814 masterwork Ariadne Asleep on the Island of Naxos is one such example. Vanderlyn painted Ariadne in Paris and hoped for this work to announce—to a New York City audience—that he was eminently qualified to paint neoclassical history paintings. But whereas this painting was a hit when it was shown at the annual Paris salon, the (comparatively) prudish American audience responded negatively to Ariadne’s lack of clothing.

The Greek Slave is even more exposed than Ariadne in Vanderlyn’s painting (if we consider, for example, the drapery that comes across the top of her left thigh). So why was this sculpture so successful, when Vanderlyn’s painting had been rejected by American audiences? The Greek Slave is a generation or two later, but this difference in time—from 1814 until 1841—cannot be the only reason why one was accepted and other not.

Many believe the primary reason why The Greek Slave was so popular was because of the means by which the figure came to be nude. Her clothing was not removed because of an amorous tryst, like Ariadne’s. Although her clothing may have been stripped away, she remained cloaked and covered in her Christian piety. The Reverend Orville Dewey summed this up in an 1847 article in The Union Magazine:

“The Greek Slave is clothed all over with sentiment; sheltered, protected by it from every profane eye. Brocade, cloth of gold, could not be a more complete protection than the vesture of holiness in which she stands.”

The art-viewing public agreed, and the popularity of this work—a popularity that likely exceeded the work’s aesthetic merits—catapulted Powers to international fame. One of the contributors to the impact of this work was the way in which viewers could consider this both a historical and allegorical composition. In addition to being based upon an event taken from the Greek War of Independence, it was also topical to the situation of slavery in the United States.

A work admired around the globe

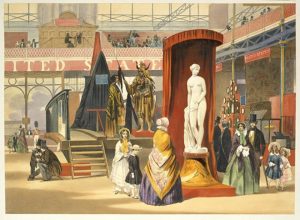

John Absalon, The Greek Slave on view in the East Nave of the Great Exhibition in the Crystal Palace, London, 1851, hand-colored lithograph, 27.1 × 37.6 cm, published by Lloyd Brothers & Co., 1851 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

These were the connections viewers consistently made when the sculpture was first shown to great fanfare in London in 1845, and then when it toured the United States two years later. It made an appearance at the next two world’s fairs—London’s Crystal Palace in 1851 and the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1855. At each stop, viewers made the connection between the statue and rising anti-slavery sentiment in the United States.

Beyond his six versions of The Greek Slave, Powers continued to contribute to the field of sculpture during the course of his long career. As an inventor, he patented new files and rasps, and developed an easier-to-use pointing machine that aided in the creation of marble copies of his works. He also developed a new finishing technique that allowed him to closely recreate the appearance of human flesh on the finely grained Carrara marble so preferred by Florentine sculptors. But it was The Greek Slave more than any other element that secured Powers’s reputation as an American sculptor of the highest rank and it remains one of the most important and enduring works of American sculpture.

Additional resources:

The Greek Slave at the National Gallery of Art, The Brooklyn Museum, Yale University Art Gallery, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum (the two other copies are held by Raby Castle, England, and Newark Museum, New Jersey)

Essay on Hiram Powers from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Smithsonian exhibition on the plaster cast of The Greek Slave

Replicating The Greek Slave from Smithsonian.com

Special issue on The Greek Slave from 19th-Century Art Worldwide

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”PowersSlave,”]