Warning: this video discusses racial violence. MASS Design Group, The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, 2018 (Equal Justice Initiative), Montgomery, Alabama. Speakers: Dr. Hilary Green and Dr. Steven Zucker

Essay by Dr. Renée Ater

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, 2018, Montgomery, Alabama (photo: Shawn Calhoun, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Located in Montgomery, Alabama, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice is the first monument to commemorate the over 4,000 African Americans who were lynched in the United States between 1877 and 1950. The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) envisioned and realized the memorial as “a sacred space for truth-telling and reflection about racial terror in America and its legacy.”

Meta Warrick Fuller, In Memory of Mary Turner: As a Silent Protest Against Mob Violence, 1919, painted plaster (Museum of African American History, Boston & Nantucket)

While writing my dissertation on the sculpture of Meta Warrick Fuller, I investigated the history of lynching in the United States. My research was motivated by the fact that Fuller had created a small painted plaster to honor the memory of Mary Turner, a pregnant woman who was lynched in Brooks County, Georgia, in 1918. I was interested to see if Turner was identified in the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which I discovered she was. I also was deeply curious as to how EJI would handle the visual representation of trauma and violence. At the end of April 2018, I flew to Atlanta, rented a car, and drove through the Georgia and Alabama countryside to Montgomery to participate in the opening ceremonies and the two-day social justice conference.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, opened 2018, Montgomery, Alabama (photo: Soniakapadia, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Sited on six acres of land, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice is an arresting and emotionally powerful memorial to lynching victims. EJI with MASS Design Group conceived the memorial as a sober and sacred site where people can gather and reflect on America’s history of slavery, lynching, and racial inequality. EJI believes that such a monument will allow for national reconciliation and redemption.

Peace and Justice Memorial Garden, The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, 2018, Montgomery, Alabama (photo: Dr. Renée Ater)

Peace and Justice Memorial Garden

The memorial includes multiple components: a garden, four sculpture groupings, explanatory texts and quotations, and a temple-like structure with hanging rectangular boxes made of corten steel. Visitors first encounter the Peace and Justice Memorial Garden before entering the long hallway of the main entrance. Within the garden are native plantings of flowers and shrubs and the so-called “Memory Wall: Strength,” a brick arched wall from the Montgomery Theater, built in 1860, which enslaved masons constructed. The garden is intended as a contemplative space as well as a place to acknowledge past and present African American laborers in Montgomery. From the garden, a serpentine pathway leads to the entrance of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

Entrance, National Memorial for Peace and Justice, 2018, Montgomery, Alabama (photo: Dr. Renée Ater)

Telling the story of slavery and lynching

A quotation from Martin Luther King Jr. greets you as you enter the memorial. Placed along a wooden slat wall, it reads: “True peace is not merely the absence of tension, it is the presence of justice.” This quotation frames the meaning of the memorial and the overall social activist and reparative justice mission of EJI. EJI is “committed to ending mass incarceration and excessive punishment in the United States, to challenging racial and economic injustice, and to protecting basic human rights for the most vulnerable people in American society.” The memorial space flows in one direction, with visitors passing King’s remarks to begin a slow climb up the gently sloped landscape to the main building of the memorial.

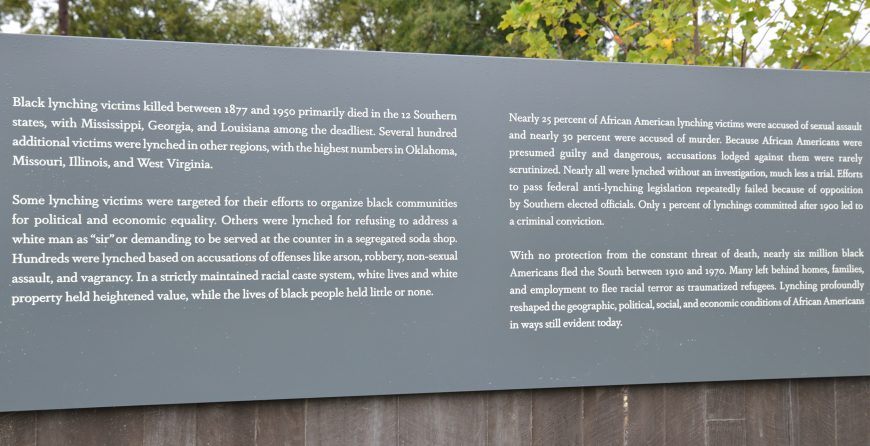

Informational plaque in the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, 2018, Montgomery, Alabama (photo: Judson McCranie, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Four large grey plaques with white lettering are attached to the concrete wall along the pathway. Evenly spaced, these texts outline a history of the transatlantic slave trade and the rise of violence in the post-Civil War period; Reconstruction and the rise of convict leasing in the South; racial terror lynching in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries; and the justifications that white Americans gave for lynching African American men and women. The texts use direct, concise language to describe the difficult historical facts of slavery and racial terror lynching.

Kwame Akoto-Bamfo, Nkyinkyim Installation, 2018, National Memorial for Peace and Justice, Montgomery, Alabama (photo: Michael Delli Carpini, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Monument to the transatlantic slave trade

In front of the first plaque, the artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo created a cast concrete, multi-figure, stand-alone monument to the transatlantic slave trade. Entitled Nkyinkyim Installation, this work presents seven semi-nude Africans who are enchained for the harrowing journey from the interior to the coast for transportation across the Atlantic. Based on the slavery memorial in Stone Town, Zanzibar, Tanzania, Akoto-Bamfo’s memorial evokes the horror of slavery through the figures anguished expressions; chained necks and manacled hands and feet; and simulated slashed backs. The most sorrowful of these depictions is of a chained young mother holding a screaming baby as she reaches across to an older standing male figure.

Memorial Square, National Memorial for Peace and Justice, 2018, Montgomery, Alabama (photo: Michael Delli Carpini, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Sacred space dedicated to lynching victims

The memorial structure suggests the form of a temple with a large peristyle. At the center of the temple-like memorial is an open space, “Memorial Square,” reached by a series of aggregate concrete steps. The grassy knoll represents spaces such as town squares and courthouse lawns used for the public spectacle of lynching. Inside the memorial, over 800 rectangular corten steel boxes, six feet in height, hang by steel poles from the ceiling at even intervals. Each of these hanging forms represents a county in the United States where a lynching took place. Names of lynching victims and the dates of their murders are laser cut into the surfaces of the boxes.

On the interior of the memorial structure, you begin on even ground, your body parallel to the coffin-like forms. If you choose, you can lean into the monument and even trace a finger across the cutout letters or feel the uneven surface quality. As you descend into the memorial, the corten steel boxes rise high above, suspended in the air and no longer within your bodily space. These rusted stele evoke the image of black bodies hanging from trees.

Memorial Corridor, National Memorial for Peace and Justice, 2018, Montgomery, Alabama (photo: Soniakapadia, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Along the third section of the memorial, bands of text panels in grey with white lettering identify the awful justifications for racial terror lynching including accusations of inappropriate conduct with white women, speaking out against lynching, and not showing deference to whites. After reading these difficult texts, you encounter a message of reconciliation.

For the hanged and beaten.

For the shot, drowned, and burned.

For the tortured, tormented, and terrorized.

For those abandoned by the Rule of Law.We will remember.

With hope because hopelessness is the enemy of justice.

With courage because peace requires bravery.

With persistence because justice is a constant struggle.

With faith because we shall overcome.

This text asserts unequivocally the power of this memorial to act as a remembrance device and as a space where the horror and trauma of lynching is framed in the context of peace.

Wall with flowing water, National Memorial for Peace and Justice, 2018, Montgomery, Alabama (photo: Judson McCranie, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Nearby, water flows down the final long wall of the memorial. Metal lettering asserts that all victims of lynching now will be remembered. “Thousands of African Americans are unknown victims of racial terror lynchings whose deaths cannot be documented, many whose names will never be known. They are all honored here.” The slow sound of water cascading down the wall allows space for contemplation, as you are able to sit along rough-hewn seating across from the water feature.

National Memorial for Peace and Justice, 2018, Montgomery, Alabama (photo: Michael Delli Carpini, CC BY-NC 2.0)

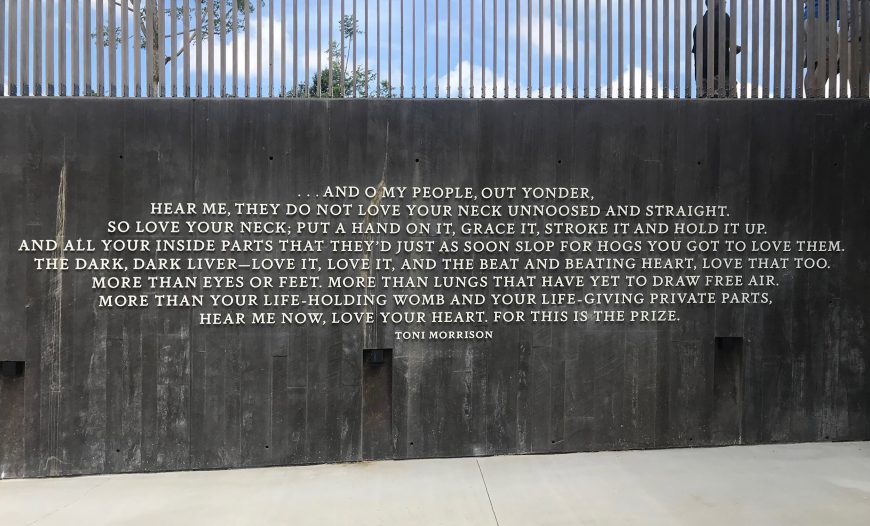

When you exit the memorial to the surrounding park, you encounter a final quotation from Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved that stresses the power of love.

And O my people, out yonder, hear me, they do not love your neck unnoosed and straight. So love your neck; put a hand on it, grace it, stroke it and hold it up. And all your inside parts that they’d just as soon slop for hogs, you got to love them. The dark, dark liver—love it, love it, and the beat and beating heart, love that too. More than eyes or feet. More than lungs that have yet to draw free air. More than your life-holding womb and your life-giving private parts, hear me now, love your heart. For this is the prize.

Duplicate monuments, National Memorial for Peace and Justice, 2018, Montgomery, Alabama (photo: Dr. Renée Ater)

Duplicate monuments

In the park, MASS and EJI included a field of duplicate monuments. Rather than hang from a roof, the corten steel boxes now serve as cenotaphs lying flat on the ground in long rows. They are waiting to be claimed and installed in the counties they represent. For EJI, the duplicate monuments serve as “a report” as to which counties have confronted the difficult history of lynching and which have chosen to not deal with such a painful legacy. EJI believes this process of claiming the duplicate monuments will “change the built environment of the Deep South and beyond to more honestly reflect our history.”

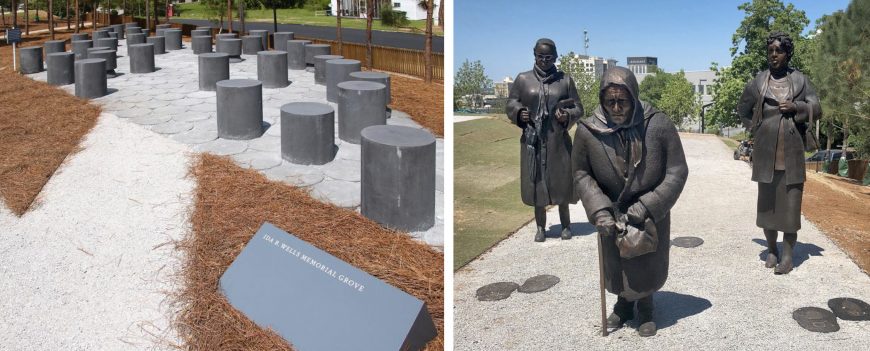

Left: Ida B. Wells Memorial Grove; right: Dana King, Guided by Justice, 2018. National Memorial for Peace and Justice, 2018, Montgomery, Alabama (photos: Dr. Renée Ater)

Sculpture in the park

Three additional groups of sculpture are integrated into the park. The Ida B. Wells Memorial Grove honors the early twentieth-century anti-lynching activist and writer. It contains over forty black granite cylinders of various heights that visitors can sit on and reflect. In Guided by Justice, Dana King created three life-size bronze statues of black women dressed in coats as they “walk” on the pathway. These three statues of women at various stages of life symbolize the women arrested in 1955 for challenging racial segregation on Montgomery’s public buses.

Hank Willis Thomas, Raise Up, 2016, National Memorial for Peace and Justice, 2018, Montgomery, Alabama (photo: Dr. Renée Ater)

The final sculpture is by Hank Willis Thomas and represents systemized police violence directed towards African American men. Raise Up is a long horizontal, free-standing concrete wall with ten bronze portraits of black men shown from the neck up with their hands raised above their bald heads. These monuments with Akoto-Bamfo’s multi-figure statue of enslaved persons underscore the main themes of the memorial and of EJI’s work: slavery, lynching, segregation/resistance, and mass incarceration.

Elizabeth Alexander’s “Invocation”

As visitors exit the National Memorial to Peace and Justice, they encounter the haunting lines of the poet Elizabeth Alexander’s “Invocation.” In the lines of her poem, Alexander asserts that the African American victims of racial terror lynching will not be forgotten, nor lost in the telling of U.S. history. Each name—“a holy word”— is forever etched on this memorial and into the nation’s collective memory.

The wind brings your names.

We will never dissever you names

nor your shadows beneath each branch and tree.The truth comes in on the wind, is carried by water.

There is such a thing as the truth. Tell us

how you got over. Say, Soul look back in wonder.Your names were never lost,

each name a holy word.

The rocks cry out—call out each name to sanctify this place.

Sounds in human voices, silver and soil,

a moan, a sorrow song,a keen, a cackle, harmony,

a hymnal, handbook, chart,

a sacred text, a stomp, an exhortation.Ancestors, you will find us still in cages,

despised and disciplined.

You will find us still mis-named.Here you will find us despite.

You will not find us extinct.

You will find us here memoried and storied.You will find us here mighty.

You will find us here divine.

You will find us where you left us, but not as you left us.Here you endure and are luminous.

You are not lost to us.

The wind carries sorrows, sighs, and shouts.The wind brings everything. Nothing is not lost.

Additional resources

EJI Director Bryan Stevenson explains why it is necessary to create memorials for lynching victims.

What is a racial terror lynching? EJI Director Bryan Stevenson explains.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice on Equal Justice Initiative website

MASS Design group page on their design for the memorial

Contemporary Monuments to the Slave Past

Renee Ater’s public history blog

Julie Buckner Armstrong, Mary Turner and the Memory of Lynching (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2011).

Fritzhugh Brundage, Under Sentence of Death: Lynching in the South (Durham, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997).

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:11] We’re in Montgomery, Alabama, at the Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice. We’ve just walked through, and I feel emotionally overwhelmed.

Dr. Hilary Green: [0:18] I’ve been here over 20 times, and every time, I’m teary and emotional but in a good way because in those emotions, I’m able to feel and do what the memorials intend. To have an inner peace, but also a way to go forward and heal on this unspoken history in a way that honors the people who were the victims of lynching.

Dr. Zucker: [0:39] When I grew up, lynching was almost never spoken about. It is America’s great shame.

Dr. Green: [0:45] I heard some of it growing up in an African American family. They used lynching as a way to educate us as children of what not to do. When it was taught in schools in Massachusetts, that’s where I grew up, in the Boston area, it was individual actors. It wasn’t seen as widespread.

[1:05] This memorial shows it was political. It was violence that was widespread in almost every state of the United States except for a handful. That becomes very clear as you walk through this memorial.

Dr. Zucker: [1:15] Walking through, starting at the top of the hill and winding down through a descending ramp so that these large COR-TEN steel memorials begin to hang over your head, one after another, after another, multiplying.

Dr. Green: [1:30] You’re going through the cycle of a lynching, from the person while they were still alive and upright and at eye level to when they are strung up and over your head. All you see at the base is the county.

[1:47] At the end, when they’re laid out in coffin-like style, giving them the dignity in a burial that they never had. It gets overwhelming when you see nothing but bottoms of the pieces and you no longer can see the names.

Dr. Zucker: [1:57] That idea that this memorial is offering a kind of solace, offering a kind of funerary honor that these people had never been afforded is so moving. It feels to me that it has come too late, but I’m grateful that it has come at all.

Dr. Green: [2:12] They were not these unknown men, women, and children. They were fathers, they were mothers. The crimes that they were accused of, a man, a minister, marrying someone is the reason why he was killed. Military veteran returning back from the Spanish-American War killed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. A husband, his family was killed because he voted. People came back to the house, killed his mother, his wife, and two children.

[2:40] It becomes clear that they were people, they were community members, and in death, they still deserve honor.

Dr. Zucker: [2:47] Lynching was a tool of repression. It was a tool to subjugate, to maintain the surveillance, [the] terrorizing slave state that had existed before the war.

Dr. Green: [2:57] It’s the ultimate form of what Koritha Mitchell calls “know-your-place aggression”. If you go outside your place for organizing a union, you could be killed. If you were to vote, you could be killed. If you were reprimanding children to get them to stop throwing rocks at you, you were lynched.

[3:15] It was the way to keep people submissive. What I found telling is when you have more than 1 person killed on a day around election times for voting, around labor organizing, and you have not 1 person but 5 people, 10 people, 20 people.

Dr. Zucker: [3:33] Or entire communities that are attacked and burned.

Dr. Green: [3:35] Like Elaine, Arkansas and the Tulsa Massacre. This is a way to protect a system of white supremacy, was political violence with political intent.

Dr. Zucker: [3:51] The challenge was, how do you take that history of terror and translate that through architecture, through memorial sculpture, into something that is meaningful in the 21st century?

Dr. Green: [3:59] This is the brilliance of this memorial. You are just settled with the name and the date, and even when not known, “Unknown” as a name. You get a history lesson in the way that you can then have deeper conversations that you would not have before.

[4:16] That’s why this memorial is striking and why it’s bringing both peace for a community to heal but also justice for the victims of this heinous crime. Ida B. Wells says that this was a national crime and we need to acknowledge it as a nation.

Dr. Zucker: [4:31] When I was walking through, looking at the justifications of why people were lynched, especially at those that were murdered because they had voted, it’s hard not to look at contemporary politics and the efforts to suppress voting now. This is not history, in a sense. This is part of a continuing legacy.

Dr. Green: [4:50] That’s one of the things, a continued legacy of resistance. A refusal to accept one’s place and understand that the ballot matters the most, and why it’s dangerous to be educated and to be politically savvy.

[5:04] Those are why we’re having these debates now over voting rights, but also what gets taught in the classroom. Because lynching was not taught in the classroom. When you see it as not a one-off thing but a long legacy in history, it becomes different in the present.

Dr. Zucker: [5:16] Walking up to one of these rectangular forms, they function as abstract human bodies, but also as grave markers, and transform that figure into a remembrance.

Dr. Green: [5:28] The families behind those names never forgot. One of the most striking walls says, “We will remember.” Families remembered. Communities remembered. That refusal, that act, is one of the reasons why we can have this memorial, because it went from safe spaces within the Black community to now national conversation.

Dr. Zucker: [5:50] The research and outreach to those families to gather those memories and bring them together here.

Dr. Green: [5:57] This wasn’t unknowable. Families had this, but also newspapers documented these. Government reports and politicians used this and openly discussed this. There’s an acknowledgment of the families who never forgot and never got that healing, that they too could heal, not just the nation. And that what they did in this counter-act of commemoration in scrapbooks and family diaries was valid. And that concern is now shaping the national conversations of, what do we do now?

[0:00] [music]