Juan de Pareja, The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1661, oil on canvas, 225 x 325 cm (Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:04] We’re at a special exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art of the work of Juan de Pareja, a 17th-century painter, finally being given the attention that he deserves.

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:17] Ironically, this artist is known mostly through a portrait of him by the great Spanish painter, Diego Velázquez.

Dr. Harris: [0:24] We’ve always known that in that famous painting by Velázquez, that’s been so long admired, the man featured in the painting, Juan de Pareja, was enslaved, and his enslaver was Diego Velázquez.

Dr. Zucker: [0:39] But Pareja was also an artist. We’re standing in front of a very large canvas, what we think was a significant commission. This painting is 10 feet across.

Dr. Harris: [0:50] The subject is the Calling of Saint Matthew. It’s the story of a moment of conversion, the moment of a life-changing event, when Matthew is approached by Christ and called to become one of his apostles, and who at first questions that calling.

Dr. Zucker: [1:08] All of that takes place in the right half of the canvas. Christ is standing in blue and red. He looks slightly down, and looking up to him is a man dressed in the most extravagant costume. This is Matthew. Before, riches: we see pearls, we see gold and silver coins on top of this gloriously painted West Asian carpet.

Dr. Harris: [1:32] Those coins spilling out of the bag signal the life that Matthew is turning away from. This life of worldly power and influence, and on the cusp of accepting this spiritual calling.

[1:48] We can think about the figures and the space on the right side of that column behind Matthew as this spiritual space, which is spare. Where we see a view to nature. Where we don’t see any of those expensive household goods that are so over-the-top in the left-hand side of the painting.

Dr. Zucker: [2:09] Matthew is at this moment of indecision. Is he going to give up this wealth? Is he going to follow Christ and take a spiritual journey? He seems to be gesturing, almost as if he’s saying, “You mean me?” Questioning how could he possibly be asked to follow Christ.

Dr. Harris: [2:25] Matthew is certainly the most extravagantly dressed of the figures that we see on the left-hand side of the painting. Some of the figures are looking up at Christ, some of them don’t seem to notice him.

[2:36] But as our eye scans the figures from right to left, from Christ through this room of figures, the golden urns glimmering in the light below the window, the painting on the back wall, the books, all of these signs of wealth and prosperity, at the far left, we see a self-portrait of the artist himself. We see Juan de Pareja.

[2:58] In his hand, he holds a piece of paper which contains his signature, “Juan de Pareja made this,” and the date of the painting.

Dr. Zucker: [3:06] This is the only figure that looks out directly at us. He stands nobly; we can see almost his entire body. In fact, that’s the only case beyond Christ in this painting where that happens, and importantly, he’s dressed as a member of the aristocracy, as a nobleman.

Dr. Harris: [3:22] Specifically, the sword that he carries is a clear indicator of status. I think it’s important for us to remember how clear a sense of social hierarchy there was at this time, particularly in Spain. Jews, Muslims, people of color, people of African descent, like Pareja, had significant restrictions placed on their lives.

Dr. Zucker: [3:48] The artist was born in Spain, but he is of African descent and one of two figures in this painting that are Black.

Dr. Harris: [3:56] We see the other Black figure behind the column, although mostly obscured by that point of light above Matthew’s head.

Dr. Zucker: [4:04] It’s not unusual to see a Black figure in a painting, but it is unusual to see a Black figure portrayed in such an ennobled way.

Dr. Harris: [4:12] We know that in Spain at this time, there was a significant enslaved population. Pareja does get manumitted by Velázquez before this painting is painted.

[4:24] It’s important for us to keep in mind not only Velázquez’s portrait of Pareja himself but also Velázquez’s self-portrait, where he portrays himself within the court of King Philip IV of Spain as a way of showing, of proving his noble status, his status above the level of a normal artist by his presence within the court.

[4:51] So we know that Velázquez had this concern for his own status, and clearly, Pareja is concerned with his status in this painting.

Dr. Zucker: [5:01] Velázquez’s own striving for social status was augmented by being a slave owner.

Dr. Harris: [5:09] Interestingly, we see this moment where Matthew gives that up in favor of a spiritual life.

[5:15] [music]

Jesus saw a man called Matthew at his seat in the custom house, and said to him, ‘Follow me,’ and Matthew rose and followed him.Matthew 9:9

This painting interprets the preceding passage from the Gospel of Matthew in the Bible; Jesus is on the right-hand side dressed in red and blue robes and standing near a seated man. This man is a tax collector named Levi, shown in this painting wearing a turban, soft fur, silk, and jewelry. Levi sits at the far right of a table covered with a patterned carpet likely from West or South Asia, upon which a purse with gold and silver coins, strings of pearls, and other jewelry are displayed. Jesus makes an unusual request of Levi: abandon this material life and follow Him on a spiritual journey instead.

Juan de Pareja, The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1661, oil on canvas, 225 x 325 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid, photo: Steven Zucker)

Levi, who according to the Bible was a Jewish tax official, is taken by surprise, and points to himself as if to say, “you can’t mean me.” Nevertheless, Levi goes on to accept Jesus’s request, changing his name to Matthew, and writing the Gospel of Matthew in the Bible, in which he narrates his conversion to Christianity. This story of conversion is the subject of the 1661 painting, The Calling of Saint Matthew by the Afro-Hispanic artist Juan de Pareja. This work is about assuming and asserting a new identity, both for the Biblical figure Matthew as well as for the artist of the work, Juan de Pareja, a Black artist in 17th-century Catholic Spain.

Self-portrait of Juan de Pareja (detail), Juan de Pareja, The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1661, oil on canvas, 225 x 325 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid, photo: Steven Zucker)

Juan de Pareja’s The Calling of Saint Matthew

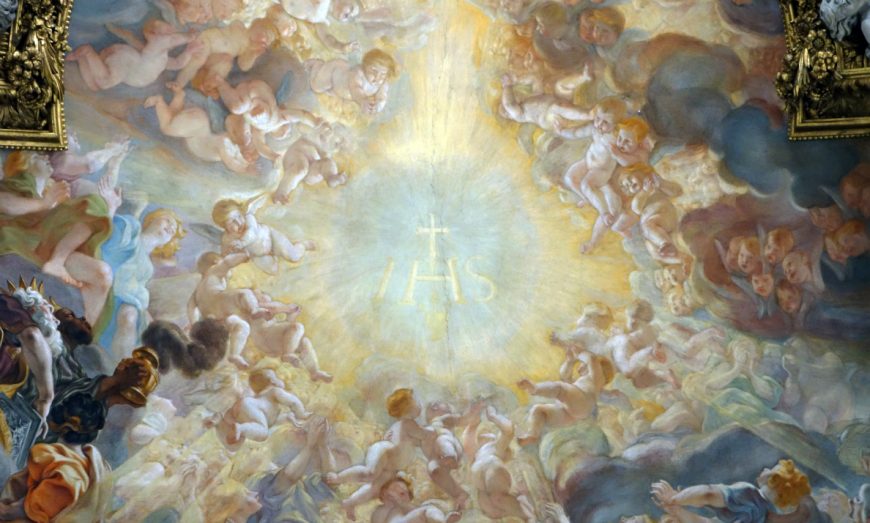

In this large painting, which stretches over 10 feet wide and reaches over 7 feet high, the space of the tax office is unevenly divided by a marble column into two different zones and times. One side of the column represents the material, earthly world while the other represents the spiritual realm. The two converge at the figure of Matthew who sits before the column as a pivot point between these areas. The right side of the canvas (the spiritual realm) is occupied by Christ and three of his disciples, two of whom are distinguishable by stars illuminated above their heads. Christ himself is identified by a white halo around his head and is illuminated both by the light from the open window on the left of the painting and by the light from the doorway behind him. This holy group wears simple robes and are barefoot. By contrast, to the left of Matthew, the material world is crowded with account-books, sheets of paper, gilded urns, and a large painting on the back wall. This space is filled with tax officials, bookkeepers, and others wearing elegant clothing of the 17th century. The bookkeeper, who sits scribbling figures with a quill pen onto paper, wears a pair of eyeglasses, which did not exist at the historical time of Jesus.

Not all of the people in the office look up from their work to witness this pivotal moment. Some look to Jesus and Matthew and suspend their activities. Others, like the bookkeeper, stay focused on the tasks before them. The exception is the reaction of the man on the far left of the painting. He is the only one who connects directly with the viewer and invites us to witness this momentous event on a busy day at the tax office: the moment of conversion of the Jewish Levi into the Christian Saint Matthew. The man who connects directly with the viewer is a self-portrait of the artist, Juan de Pareja. He makes himself identifiable by holding a piece of paper which he signed and dated in Latin, “Jo. ̊de Pareja F[ecit].1661” (Juan de Pareja made this. 1661).

Pareja’s symbolic self-portrait as a free Spanish nobleman

Pareja’s The Calling of Saint Matthew contains the only known self-portrait made by an Afro-Hispanic artist in Europe between 1480–1700 and is an extraordinary statement of freedom and status in 17th-century imperial Spain, where Afro-Hispanic enslaved people and formerly enslaved people were forbidden from becoming professional painters. This prohibition had two historical elements: the tradition dating back to ancient Greece (a culture that also enslaved people) which established that only a free man could be a painter and the Catholic Spanish prohibition against “New Christians” (those who converted to Christianity) from becoming professional artists. “New Christians” would have included all Africans, including those who were Jewish or Muslim, as well as non-African Jews and Muslims.

Self-portrait of Juan de Pareja (left) with other figures (detail), Juan de Pareja, The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1661, oil on canvas, 225 x 325 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid, photo: Steven Zucker)

To claim his right to work and to circumvent these restrictions, Pareja depicts himself as a free, noble “Old Christian” in this work. Standing in a three-quarters pose, showing off his fashionable clothes and shoes, Pareja sports stylish facial hair, bears a folded piece of paper in his right hand and has a sword hanging on his left side. Noticeably, Pareja also portrays himself with light skin in this painting.

Diego Velázquez, King Philip IV of Spain, 1628–29, oil on canvas, 201.2 x 109.5 cm (Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston)

Bearing a sword was symbolic of hidalguía, or a symbol of nobility and purity of blood. Only hidalgos could wear swords. The sword was a social attribute at this time of “Old Christians,” or those who were born into white Spanish families and whose Christianity was well attested. “Old Christians” were considered to be “limpios de sangre,” meaning “of clean blood” rather than “of tainted blood,” which referred to people of Jewish, Muslim, Black or “Indian” background. Therefore, the faith of “Old Christians” was considered to be “pure” and authentic.

In 17th-century Spain, which controlled colonies in North America (including the Caribbean) and South America, and actively participated in the global slave economy, all of these visual elements—pose, dress, accessories, and particularly skin color—were markers of status and social position in painted portraits and images. For example, the king of Spain, Philip IV, was painted striking a very similar pose in luxurious clothes and bearing the same attributes (a folded note in his right hand and a sword under his left) in numerous portraits in the first half of the 17th century by Diego Velázquez, Juan de Pareja’s former master and teacher.

If Pareja was prohibited from being a professional painter because he had been enslaved and was also considered a “New Christian,” he nevertheless adopted the visual language of status and privilege in 17th-century Spain for his self-portrait in The Calling of Saint Matthew. Here, he claims that he is an “Old Christian” hidalgo in Madrid, the center of the Spanish empire, and therefore has a right to be a free and respected artist.

Diego Velázquez, Juan de Pareja, c. 1650, oil on canvas, 81.3 x 69.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Juan de Pareja

Juan de Pareja was born in the city of Antequera in southern Spain in 1606 and signed The Calling of Saint Matthew eleven years after Diego Velázquez freed him from enslavement in Rome in November of 1650. After attaining his freedom from enslavement, Pareja forged an independent career, painting religious works and portraits, some of which are signed or signed and dated. Pareja is also the subject of a portrait painted by Velázquez in 1650, eight months before he was manumitted and eleven years prior to Pareja’s The Calling of Saint Matthew. Here, Velázquez depicts Pareja as a Spanish gentleman, including wearing elegant contemporaneous Spanish attire and a sword, as he will in The Calling of Saint Matthew.

Pareja’s biographer, Antonio Palomino, recorded in 1715 that the Juan de Pareja portrait “gained such universal applause that in the opinion of all the painters of the different nations everything else seemed like painting but this alone like truth.”

Left: Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas, c. 1656, oil on canvas, 320.5 x 281.5 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid); right: Juan de Pareja, The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1661, oil on canvas, 225 x 325 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid, photo: Steven Zucker)

If we compare Velázquez’s depiction of Juan de Pareja to Pareja’s self-portrait in The Calling of Saint Matthew, it is clear that Pareja follows Velázquez’s template of depicting the Afro-Hispanic man as a Spanish gentleman. In his own self-portrait, Pareja depicts himself with the same hairstyle and mustache of Velázquez’s own self-portrait in the famous Las Meninas and both place themselves on the extreme left of their monumental paintings. By employing the conventions of status and nobility, Velázquez in Las Meninas and Pareja in The Calling of Saint Matthew both visually argue that artists, particularly painters, are not mere artisans who only work manually with their hands, but are gentlemen who pursue elevated and intellectual pursuits.

The striking difference between Velázquez’s portrait of Juan de Pareja and Pareja’s own self-portrait in The Calling of Saint Matthew is that Pareja’s skin appears much lighter in his own work. While we do not know what Juan de Pareja’s actual skin tone was, this discrepancy illuminates how painted portraits, either self-portraits or portraits painted by another artist, can be, and often are, fashioned to project a certain version of the sitter. In other words, while the viewer may assume that a portrait objectively portrays what that person looks like, that image is constructed, by both the artist and the sitter, to convey a certain understanding of that person to the audience.

Diego Velázquez, Self-Portrait, 1645, oil on canvas, 103.5 x 82.5 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

For example, Velázquez himself utilized dress, pose, and the presence of a sword at this side to assert his noble lineage and status in his own self-portraits (such as this example from 1645), despite the fact that he did not actually come from a noble family. Velázquez may also have had Jewish heritage, which would also have prohibited him from being considered an “Old Christian” and thus from becoming ennobled (as he became in 1659).

Yet despite bearing the trappings of a nobleman, the distinctive non-white color of Pareja’s skin in Velázquez’s portrait would have been seen as the inherent attribute that defined him as an enslaved (and thus lower class) person in 17th-century Spain and more generally in Europe. Palomino, the biographer quoted earlier, remarked about Pareja’s ethnicity: “[he was of] of a Mestizo Breed, and of an odd Hue” (de generación mestizo, y de color extraño). [1] Documentary evidence in the province of Málaga, where Pareja was born, shows that the term mestizo refers mainly to those born as the result of the union of a white male Spaniard and a Afro-Hispanic woman.

Sculpture of Saint Iphigenia, Iglesia del Carmen, Antequera (photo: Rafael Castañeda García)

While some prominent Catholic figures, including the Virgin Mary and Saint Iphigenia of Ethiopia, were often portrayed as Black saints in churches and in the Black confraternities in Spain at this time, the general association of Blackness was with the social condition of enslavement. This association lasted from the middle of the 15th century until the 19th century, corresponding to the period of the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Therefore, in Velázquez’s portrait of 1650, Pareja would have been considered by contemporary viewers to be defined by his enslaved condition and a “New Christian” due to the color of his skin. Furthermore, in Spain in the 17th century, portraits were expected to portray a “worthy subject,” meaning a person who was esteemed in their society and was considered significant enough to be remembered by future generations. [2] It goes without saying that an enslaved person was not considered a “worthy subject” for a portrait in this context.

Afro-Hispanic figure peeking out from behind a column (detail), Juan de Pareja, The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1661, oil on canvas, 225 x 325 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid, photo: Steven Zucker)

Black figures as biblical Ethiopians and “Old Christians”

Pareja’s choice to portray himself with light skin in The Calling of Saint Matthew therefore would signify power and elite status to his audience. His lighter skin, does not, however, negate his African roots and in fact may allude to a collective African past. For example, Pareja also depicts a young Afro-Hispanic man in this painting, visible directly behind Matthew’s head and next to the marble column. This is a rare appearance of a person of African descent in a Spanish painting, even if cities, such as Seville in Spain, had the largest populations of enslaved Africans in Europe at the time (estimated at up to 15% of the general population) a result of the Spain’s slave trade. The Portuguese, with the active participation of the Spanish, were responsible for the capture of free Africans from West Africa (Senegal, Gambia, and Niger) who were then sold and bought in auctions in public spaces in urban centers including Seville, Valencia, Barcelona, and Lisbon.

In Pareja’s canvas, the inclusion of the young Afro-Hispanic man may also refer to Saint Matthew’s missions in Africa. According to an apocryphal Christian text, the Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine, Matthew converted the King of Ethiopia and his family to Christianity. [3] According to this text, Matthew converted and baptized the Ethiopian princess, Iphigenia, to Christianity. She would go on to become a nun and would be known as Saint Iphigenia for her role in converting the kingdom of Ethiopia to Christianity. Saint Iphigenia was a revered figure in Spanish Catholic communities at the time Pareja’s painting was made.

In Pareja’s painting, both the young African man and Levi/Saint Matthew are placed next to a column, a traditional symbol of the foundation of the Church. Here we can interpret this column as a symbol of Christian Africa and in this way, a foundational pillar of the Catholic Church. Pareja may be suggesting that ancient Ethiopia (which included Egypt and Sudan at the time) was the first Christian nation, having embraced Christianity in the first century. This would make Christian Africans and Christians of African descent, like himself and the young man behind the column, the true “Old Christians.” [4] Thus, Pareja feels entitled to self-fashion himself as a free and noble “Old Christian” and could therefore proclaim his legitimate right to be an independent painter.

Juan de Pareja, The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1661, oil on canvas, 225 x 325 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid, photo: Steven Zucker)

Juan de Pareja: a painter fit for a king

In The Calling of Saint Matthew, Juan de Pareja also positions himself opposite Christ and Levi/Saint Matthew. He reminds his audience about the paradoxical position occupied by Afro-Hispanic enslaved people and formerly enslaved people in 17th-century Spain. They were legally classified as commodities with no rights and were objects of material exchange. Yet, Spaniards of African descent were also Christians, and thus equal to white Spaniards in the eyes of God. While he lived in bondage until 1650, Pareja, like Levi before him, chose a new identity for himself and a new path for his life, documented in this Biblical yet contemporary scene.

While we do not know who commissioned this work from Juan de Pareja, there is documentary evidence that it belonged to the most powerful client in the empire: the Spanish Crown. [5] This attests to the success of Pareja’s assertion of his new identity as a man of worth and regard, socially, religiously, and artistically. Pareja presented his own likeness in a way that conformed to the visual language of status at the time, and in a manner that served his own ambitions.