Elisabetta Sirani, Portia Wounding her Thigh, 1664, oil on canvas, 101 x 138 cm (Collezioni d’Arte e di Storia della Fondazione della Cassa di Risparmio, Bologna)

yet now I have tried myself, and find that I can bid defiance to pain.Portia, quoted in Plutarch, “Life of Marcus Brutus,” from Parallel Lives

The point of Portia’s knife glints in the light of her private chamber. Its sharp blade, normally used for cutting nails, points downward, ready to puncture her flesh. The skirt of her dress is hiked up to reveal three stab wounds, out of which blood spills down her thigh. In spite of this, Portia appears calm. Her actions go unnoticed by four women in an adjoining room who are lost in conversation as they spin thread.

Elisabetta Sirani’s Portia Wounding Her Thigh depicts an ancient Roman story, but the fashionable wallpaper and velvet side chair in Portia’s room indicate that this version of the story takes place in a 17th-century Italian setting. Sirani primarily celebrates Portia as a courageous heroine, but also pays homage to the work’s intended owner (a successful fabric merchant) through the luxurious, jewel-toned fabrics used in the subject’s expensive gown, the mound of silk on which she sits, and the furnishings in her room.

Portia’s story

Portia Wounding her Thigh depicts a story told in Plutarch’s Parallel Lives. Portia was the wife of Marcus Brutus, a Roman politician who is best known for having conspired and carried out the assassination of Julius Caesar. According to Plutarch, Portia was aware of Brutus’s plans and eager to prove her ability to be his confidant. Portia planned to prove her trustworthiness by sending her attendants away and, using a small knife, cutting a gash in her thigh. When Brutus saw her wound, Portia described her ability to endure pain as evidence of her trustworthiness, and she ultimately became his secret keeper. In Lives, Plutarch describes Portia as being “addicted to philosophy . . . and full of courage.” His description departs from the expectations of ancient Roman wives, who were believed to have lower intellects and be submissive to their husbands. Plutarch’s writing was a rich source for Italian artists in 17th-century Europe who produced works that featured Greek and Roman stories. In addition to Elizabetta Sirani, other painters that took up the subject of Portia included Guido Reni, Luca Giordano, and Jacques Bellange. Sirani’s work, however, differs from those of her male counterparts in several noteworthy ways.

Courage, not conformity

Sirani positions the viewer in Portia’s room and close to her, making us witnesses to her plan. She sits on a mound of red and gold silk at the right side of the canvas and props her sandaled foot on a chair at the left. Portia’s raised right arm and extended right leg create diagonal lines that intersect at her torso, urging us to take in her sumptuous red and white gown and her green shawl with gold brocade. She wears a jewel-encrusted gold chain that wraps around her bare shoulder and drapes across her chest. Portia’s bare skin is emphasized, drawing our attention to her serene expression, the wound in her leg, and her relaxed left hand that holds the toilet set from which she took her weapon.

At the left of the painting, an open doorway reveals an adjoining room where Portia’s attendants are engaged in winding silk. A woman dressed in blue bends down to retrieve thread from her basket, while another, dressed in white, holds a large bobbin. Behind them stands a third woman in red, who holds a winder to prevent the thread from tangling. She peers at a fourth woman wearing a turban, who enters the scene. Although Sirani depicts the women at work, they appear more interested in their gossip. In contrast, Portia is shown as a heroine, both physically and emotionally set apart from the other women. Instead of conforming to the expectations of Roman wives, Sirani’s Portia defies them by exhibiting bold courage as she carries out her plan.

Left: Guido Reni, Suicide of Porcia, c. 1625–26, oil on canvas (Museum of Fine Arts of Rennes, France); right: Jacques Bellange, The Suicide of Portia, 1612–16, etching with stippling and engraving, 24.4 × 18.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Elisabetta Sirani (attributed), Judith with the Head of Holofernes, c. 1638–65, oil on canvas, 129.5 x 91.7 cm (The Walters Art Museum)

Sirani’s painting differs from other 17th century representations of Portia that mostly focused on her death by suicide. Works by Guido Reni, Luca Giordano, and Jacques Bellange depict her as an idealized tragic martyr, preparing to swallow coals in grief after learning of Brutus’s death. Sirani departs from this convention, focusing instead on a story about her bravery and agency. Although no writing on this subject by the artist survives, it is important to note that Sirani frequently portrayed virtuous women in heroic terms. In addition to Portia Wounding her Thigh, she also painted scenes featuring ancient and Biblical women, including Judith, Mary Magdalene, and Timoclea. These figures come from different historical and religious backgrounds, but are thematically linked in terms of how they are portrayed: as calm, graceful, and beautiful women whose heroism stems from their steadfast commitment to virtue, family, and nation.

For example, Sirani’s Judith with the Head of Holofernes captures a moment from the Book of Judith in which the protagonist decapitated the Assyrian General Holofernes with his own sword in order to save her people, the Israelites, from being captured by his army. Like Portia, Judith wears an elaborate gown and luxurious jewelry. Her gold brooch, jewel hairband, and pearl earrings glitter in a light source that comes from the right side of the painting. She depicted in the moments after the assassination, and in the middle of another gruesome action: her hands grip the hair on Holofernes’ severed head as her maidservant guides it into a cloth bag. In spite of this, she exudes effortless calm, gazing out and away from the scene.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes, c. 1623–25, oil on canvas, 184 × 141.6 cm (Detroit Institute of Arts)

Judith’s placid expression differs from other versions painted by Sirani’s contemporaries. Artemisia Gentileschi, for example, utilized tenebrism to heighten the drama of the moment in which the heroine and her maidservant pause to listen for passersby. Although Gentileschi and Sirani portray the same moment of the story, their heroines’ strength seems to come from different sources. Gentileschi’s Judith grips the sword with a firm hand, its hilt still dripping with Holofernes’ blood. The single light source illuminates her furrowed brow, making her appear alert and ready to defend herself if needed. While Gentileschi’s painting is enmeshed in tension, Sirani’s expresses a quiet fortitude that emanates from Judith’s measured gaze. Though she tightly grips on Holofernes’ head, Judith appears lost in thought, as if drawing strength from within.

Sirani’s Portia and Judith are both shown in the midst of violence, but the gory nature of their choices is minimized. Instead, the viewer is encouraged to pause and contemplate the intricate details of the scene—from the sumptuous fabric and glittering jewels to the naturalistically modeled figures—before ultimately taking in the protagonists’ expressions. On the surface of each painting, the women exhibit feminine virtues of restraint and fashionable elegance, modeling contemporary social expectations for a 17th-century viewer. Nevertheless, those with knowledge of the original stories behind each work would have understood that Sirani’s Judith, like Portia, also demonstrates unyielding strength in her resolve to carry on with courage in the face of danger.

Fashioning a new heroine

Side chair, late 16th century, walnut and leather, Florence, Italy, 121.3 × 49.5 × 41.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Although the story was set in ancient Rome, Sirani’s figures are dressed in 17th-century fashion, and Portia’s rooms have the furnishings of a wealthy Italian home. The silk fabric on which Portia sits glistens in the room’s light, its warm jeweled tones echoing the illustrious glow of the gold chain on her chest. Her deep red gown matches a velvet-covered chair on the left side of the painting. Its gilt adornments, brass rivets, and fringe were highly fashionable and frequently found in wealthy Italian homes.

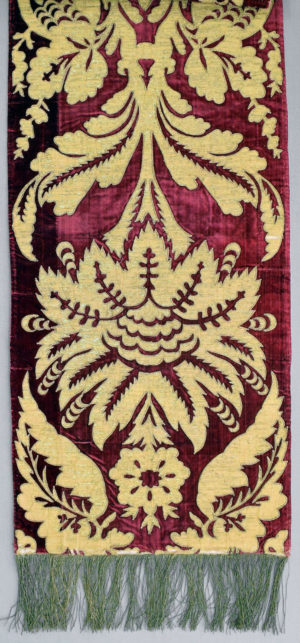

Wall panel, c. 1680–99, velvet with cloth of gold appliqué, possibly Italian, 270.5 cm x 51.5 cm (The V&A)

The red fabrics anchoring the foreground are balanced by the green wallpaper that adorns Portia’s room. 17th-century Italian wallpaper designs emulated the stylized floral patterns found in embroidery, and ranged in price depending on its material. While the least expensive wallpapers were made with woodblock prints, wealthier homes were adorned with designs made from silk, velvet, leather, and other lavish materials. Although Portia was herself a wealthy woman, Sirani’s illusionistic depiction of fabric offers insight into the original owner of the painting.

The prominence of luxury textiles in the foreground is likely an allusion to Simone Tassi, the work’s intended owner and a successful fabric merchant in Bologna. Portia Wounding her Thigh was commissioned to hang over a door in Tassi’s home. By this time, Italy had relaxed its strict sumptuary laws, and both men and women readily purchased luxurious fabrics to adorn their bodies. Silk was an especially popular textile used for dresses, shoes, buttons, wallpaper, and furniture. Sirani’s highlighting of the silk in the scene, not to mention the women winding it in the background, can be understood as a celebration of the painting’s original owner. Tassi was a strong supporter of Sirani’s work, and his collection includes four other paintings by her, all of which hung in his home. This not only indicates that Elisabetta Sirani was highly sought after during her career, but it also suggests that male collectors enjoyed works by women artists and featuring women heroines. In addition to the universally engaging subjects she produced for Italian collectors, a closer look at Sirani’s career also reveals that she interacted with prominent figures in the art world of 17th-century Bologna.

Working as an artist in 17th-century Italy

Elisabetta Sirani was one of several women who worked as professional artists in 17th-century Italy. Women in early modern Europe were not considered equals to men, and were unable to earn an independent living due to social and legal limitations. Aspiring women artists were often educated in their fathers’ studios. Gian Andrea Sirani, Elisabetta’s father, had worked with the famous Bolognese painter Guido Reni and filled the Sirani family home with many opportunities to learn. Their library owned a copy of Plutarch’s Parallel Lives, which Elisabetta studied in preparation for Portia Wounding her Thigh. When her father’s health suffered, Elisabetta assumed the responsibilities of his studio and eventually opened her own school for women artists. Two of her first students were her sisters, Barbara and Anna Maria Sirani.

Catafalque of Elisabetta Sirani, designed by Matteo Borboni pen and brown ink, brush and brown wash, red chalk on off-white laid paper, Italy, 29.9 x 16.3 cm (Cooper Hewitt)

One year after painting Portia Wounding Her Thigh, Elisabetta Sirani died at age 27 from unknown health complications. She was given an elaborate public funeral that included a life-sized effigy of the artist at her easel designed by Matteo Borboni. The magnitude of her commemoration was unusual for any woman artist in the 17th century, let alone one who had only been painting for ten years. This celebration highlights Sirani’s importance to the art world of 17th-century Bologna and indicates that she was well-known and widely celebrated. She is buried next to Guido Reni in the Church of San Domenico in Bologna.

Additional resources

Collezioni d’Arte e di Storia della Fondazione della Cassa di Risparmio, Bologna

Babette Bohn, “Elisabetta Sirani and Drawing Practices in Early Modern Bologna,” Master Drawings, vol. 42, no. 3 (2004), pp. 207–236.

Babette Bohn, “The Antique Heroines of Elisabetta Sirani”, Renaissance Studies, vol. 16, no. 1 (2002), pp. 66–70.

Babette Bohn, “The Antique Heroines of Elisabetta Sirani”, Reclaiming Female Agency, Feminist Art History after Postmodernism, eds. Norma Broude and Mary Garrard (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), pp. 81–100.

Whitney Chadwick, Women, Art and Society (London: Thames & Hudson, 1996), pp. 101–103.

Jennifer Higgie, “The Artist Paints Herself: Elisabetta Sirani, Sofonisba Anguissola, and Rosalba Carriera through the Ages,” Lapham’s Quarterly (2021).

Adelina Modesti, Elisabetta Sirani: Una virtuosa del Seicento Bolognese (Bologna: Compositori, 2004).

Adelina Modesti, Elisabetta Sirani ‘Virtuosa’: Women’s Cultural Production in Early Modern Bologna (Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2015).

Patricia Phillippy, Painting Women: Cosmetics, Canvases, and Early Modern Culture (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), pp. 23–60.

Plutarch, “Marcus Brutus,” in Parallel Lives, trans. John Dryden, ed. Daniel Stevenson (MIT: Internet Classics Archive, 2010). http://classics.mit.edu/Plutarch/m_brutus.html