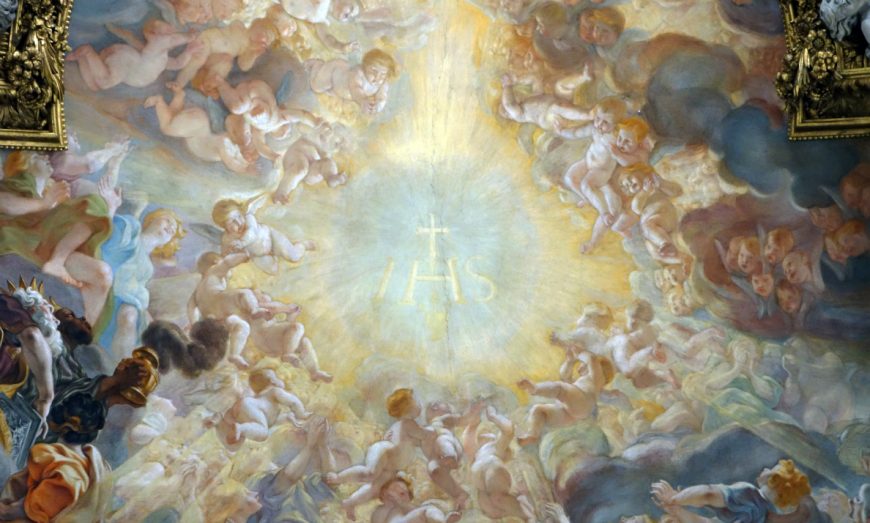

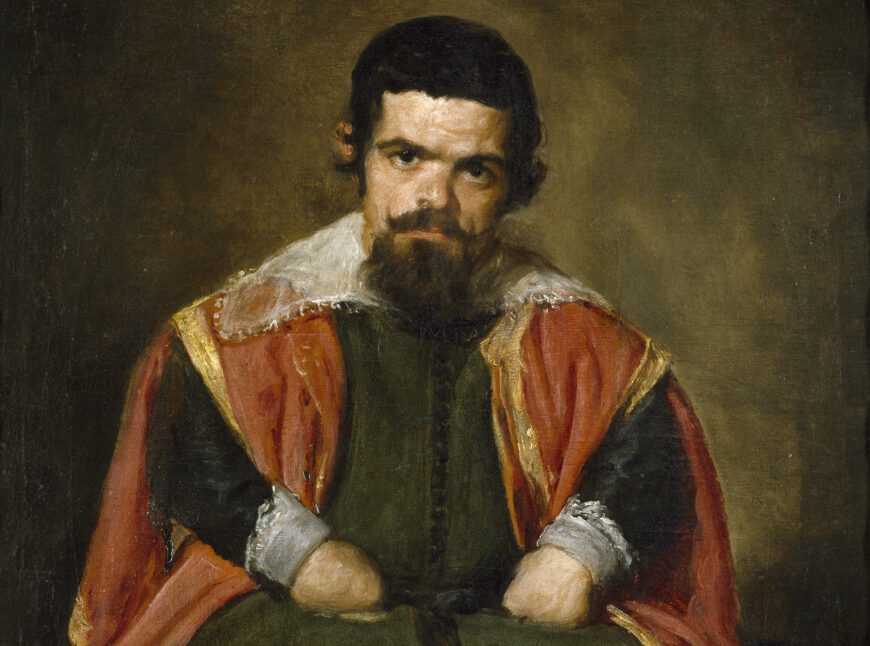

Sebastián de Morra (detail), Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez, Portrait of Sebastián de Morra, 1644, oil on canvas, 106.5 x 82.5 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid)

The compelling immediacy of Sebastián de Morra’s gaze in Diego Velázquez’s 17th-century portrait of a man employed as a court dwarf has long struck viewers as noteworthy. The figure of de Morra meets the viewer’s gaze with a frontal stare so direct that it assumes and demands equality. Given the low social position of people with dwarfism and the routine depiction of dwarfs as lesser in early modern art, this portrait’s insistence on the subject’s humanity diverges from prevalent dehumanizing attitudes towards disabled people.

Dwarfs at court

Sebastián de Morra worked as a court dwarf for King Philip IV of Spain who had received him from his younger brother Cardinal Infante Fernando in 1643. Philip IV then passed de Morra to the Prince Baltasar Carlos until the young prince’s death in 1646. De Morra himself died October 1649 after six years at the royal court.

Diego Velázquez, Portrait of Sebastián de Morra, 1644, oil on canvas, 106.5 x 82.5 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid)

Velázquez’s Portrait of Sebastián de Morra provides evidence of the European court practice of employing people with dwarfism as “court dwarfs,” companions and entertainers in a position similar to a court jester. The term dwarfism describes the physical presentation of short stature caused by a variety of genetic and medical conditions. People hired to fill positions on account of their dwarfism were expected to fulfill cultural stereotypes associated with their bodies.

The position of court dwarf was contradictory. Assumed to be intellectually feeble and benign due to their short stature, court dwarfs were granted license to speak more freely, even critically, to powerful people. They could act outside strict court hierarchy and formal protocols. [1]

While court dwarfs enjoyed comparative liberty in their speech, their working conditions were poor in early modern Europe. While not formally enslaved, court dwarfs found themselves “gifted” from court to court. Elites treated court dwarfs akin to pets, passing them around amongst themselves. Courts often viewed dwarfs not as people, but as possessions that were part of court splendor akin to collected exotic animals. [2] Physical abuse was rife. There is a documented incident of a crowd caressing a dwarf at the court of Mantua. Court dwarfs routinely suffered other physical abuse as well.

Composition

The painting presents de Morra as an individual, a worthy subject for a portrait. Velázquez depicted de Morra’s limbs shortened by dwarfism plainly without exaggeration. De Morra’s seated body fills the picture plane against a plain dark background and floor. There are no other figures, furniture, or objects available for scale or comparison. Velázquez presents de Morra as independent of the cultural practices of comparison and hierarchies of difference that defined his employment at the Spanish court.

Leaning against a plain wall, de Morra extends his legs with feet upturned towards the viewer. The rigidity of his pose contrasts with the slight tilt of his head leaning forward to better regard the viewer. Hands clenched into balls burrow onto the top of each thigh suggesting frustration or anger. Given Velázquez’s dispassionate portrayal of de Morra’s dwarfism, the viewer can assume his frustration lies outside the painting’s respectful portrayal. The clenched fists gesture to the social reality beyond the painting’s isolation of its subject as much as de Morra’s powerful eye contact.

Left: Diego Velázquez, Portrait of Sebastián de Morra, 1644, oil on canvas, 106.5 x 82.5 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid); right: Philip IV (detail), Diego Velázquez, Philip IV, King of Spain, c. 1624, oil on canvas, 200 x 102.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

De Morra’s expressive demeanor and casual pose on the floor contrasts with Velázquez’s primary subject as court painter: portraits of the king. Genre constraints dictate royal portraits maintain formality and reserve that could be undermined by the expression of transitory emotions or movement. Painting members of the court such as court dwarfs and court buffoons positioned outside rigid protocol gave Velázquez the opportunity to experiment with the genre of portraiture.

Left: Diego Velázquez, The Jester Don Diego de Acedo, c. 1644, oil on canvas, 107 x 82 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid); right: Diego Velázquez, Portrait of Francisco Lezcano, c. 1635–45, oil on canvas, 107 x 83 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid)

Other paintings of court dwarfs

Velázquez painted the Portrait of Sebastián de Morra along with portraits Francisco Lezcano and Don Diego Acedo, who were both employed as court dwarfs by Philip IV. Those two paintings are mentioned in a 1701 inventory of the Torre de la Parada, a royal pavilion and hunting lodge, which suggests they might have been commissioned directly by the king himself. Philip IV likely saw the paintings regularly.

Velázquez’s court dwarf paintings made for Philip IV proposed a way of picturing people with dwarfism quite different than typical European representations that used figures with dwarfism as a tool of comparison, as a foil to an elite figure without dwarfism. His portraits consistently portray marginalized members of the court with human dignity. Each painting presents its subject alone filling the picture plane and in possession of himself with full personhood. European portraiture typically depicted court dwarfs as incidental to the main subject of the portrait, a noble man or woman.

Rodrigo de Villandrando, Prince Philip and Miguel Soplillo, c. 1620, oil on canvas, 204 x 110 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid)

Images of an aristocratic sitter with another figure are usually called “double portraits,” but this term has been applied to a range of portraiture including images of social equals such as Raphael’s Self-Portrait with a Friend and portraits of wealthy people with enslaved servants such as Adriaen Hanneman, Portrait of Mary I. European portraits that include people with dwarfism employ the same technique as portraits of wealthy people accompanied by enslaved servants: comparing bodies to place them within a hierarchy. The dominant culture perception of lowness in certain bodies—Black bodies, disabled bodies—was intended to elevate the elite able-bodied white subject of the portrait.

The double portraits with court dwarfs invite the viewer to perceive difference between the two bodies and mark the disabled body as lower within a hierarchy, reinforcing the social status of the main subject of the portrait and the lowness and marked aberrance from normal of the person with dwarfism. [3]

Rodrigo de Villandrando’s double portrait Prince Philip and Miguel Soplillo portrays the prince, the future King Philip IV, life-sized standing tall within the large canvas and his servant Miguel Soplillo whose height reaches Philip’s waist. The painting uses the Soplillo to make Philip look tall and powerful by comparison. The prince’s hand rests on Soplillo’s head casually with a gesture of possession. As is typical with double portraits representing a difference in social status, Philip is presented as independent and Soplillo as dependent. [4]

Court dwarfs Mari Bárbola and Nicolá Pertusato (detail), Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas, c. 1656, oil on canvas, 318 x 276 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid)

The same technique of comparison used in double portraits can be seen in Velázquez’s more unusual royal portrait Las Meninas. The young infanta Margarita Teresa stands in the center of the composition. The painter dignifies the diminutive blonde princess in a variety of ways including comparing her erect posture and expected proportions to Mari Bárbola and Nicolá Pertusato, pictured near the window to the right, both employed as court dwarfs, but even placed next to the princess, they both move with autonomy choosing actions unrelated to the infanta.

Sebastián de Morra (detail), Diego Velázquez, Portrait of Sebastián de Morra, 1644, oil on canvas, 106.5 x 82.5 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid)

Complexity within a cultural tradition

Historical sources and visual depictions attest to widespread pejorative attitudes and rampant mistreatment towards people with dwarfism in early modern Europe. Visual culture and elite portraiture reinforced and contributed to these attitudes. Despite the seeming ubiquity of that mainstream prejudice, Velázquez’s portraits of court dwarfs suggest other attitudes were possible. Given Velázquez’s employment at court and the placement of the portraits in residences frequented by the King of Spain, we might even entertain the possibility that more complex attitudes exist beyond what the visual culture might indicate at first glance.