Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, The Immaculate Conception of Los Venerables (Soult Madonna), 1660–65, oil on canvas, 274 x 190 cm (Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid)

The Immaculate Conception of Los Venerables by Spanish artist Bartolomé Esteban Murillo is a picture practically overflowing with sweetness. At its center is the Virgin, almost transcendent in her loveliness, clothed in a diaphanous white gown. A brilliant blue cloak drapes over her left arm and trails behind her back. Her hands delicately cross over her chest in a gesture of devotion, while her rapturous gaze is fixed heavenward.

Emanating from the crown of her head is a warm glow, which enlivens the upper part of the celestial scene with golden light. Vaporous tufts of cloud paradoxically support her solid figure. Her contrapposto stance, with her right knee bent and her weight shifted to her left leg, adds to the undulating rhythm of the composition. A delicate sliver of a crescent moon is set at an angle for visual interest, and it encircles her foot, which is concealed for the sake of decorum beneath the pooling layers of white fabric.

Cherubs (detail), Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, The Immaculate Conception of Los Venerables (Soult Madonna), 1660–65, oil on canvas, 274 x 190 cm (Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid)

Most striking, however, is the riot of cherubs that crowd around her, populating nearly every spare inch of canvas. In their cascading, tumbling swirl, they create a sensation of rapid ascent from the cool weighty blues and grays at the bottom of the picture to the warm yellows and reds at the top. From the tumult of babies to the Virgin’s graceful form, the melodious composition and exquisite coloration, nothing sweet or charming has been spared.

The Immaculate Conception

Together, the cherubs and the Virgin represent a complex theological tenet of the Catholic Church: the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary, Jesus’ mother. This belief, which holds that Mary was exempt from the stain of original sin, though medieval in origin, was still contested until the mid-nineteenth century, when the pope officially defined it as dogma. But in the seventeenth century, when Murillo was painting, the subject was very much the matter of fierce debate, particularly in Spain. The supporters, backed by religious orders—principally, the Franciscans and the Jesuits—were opposed by the Dominicans and their allies, who argued that though Mary was indeed exceptional, the idea of a person, even Mary, being conceived without original sin would undermine the need for Christ’s redemption.

Seville, the cosmopolitan capital of southern Spain where the artist spent his entire life, was the epicenter of the devotion to the Virgin’s Immaculate Conception. There, particularly early in the century, the debate sometimes came to blows in the streets, where proponents and opponents of the belief evidently took the matter very personally.

Francisco Pacheco, Immaculate Conception, c. 1615–20, oil on canvas, 141 x 100 cm, Seville, Palacio Arzobispal

To promote the cause effectively, supporters of the belief turned to images—paintings in particular. Sevillian painter and art theorist Francisco Pacheco provided guidelines for depicting the subject decorously in his Arte de la Pintura (published posthumously in 1649, but written over the preceding decades) and completed several definitive versions, including the version at the Archbishop’s Palace in Seville. But Murillo would become the most prolific and renowned practitioner, completing dozens of versions of the subject over the course of his career. More than mere records of religious fervor, images such as these were carefully constructed persuasive tools in a hotly contested debate that defined the times.

Picturing the Virgin’s sinless conception

But how could an artist possibly depict a conception (in Catholic theology, this is the moment that the body is animated by the infusion of a soul) —much less a sinless one? Rather than attempting to represent this difficult subject literally, artists settled on a more symbolic solution. The image came to draw principally on a scriptural passage from the Book of Revelation in the Christian Bible.

And a great sign appeared in heaven: A woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars

Revelation 12:1, Douay-Rheims Translation

The chosen image was a young woman with the rays of the sun emanating from her, a crown of twelve stars at her head, and the moon at her feet. This visionary iconography was often elaborated by symbolic elements alluding to the Virgin’s purity taken from the Old Testament as well as from traditional Marian hymns, as we can see in works such as that of Francisco de Zurbarán. Zurbarán includes the spotless mirror (speculum sine macula, Wisdom 7:26) among the many elements embedded in the clouds and the palm (Ecclesiasticus 24:13–14) and tower of David (Song of Solomon 4:4) in the landscape below.

Workshop of Thielman Kerver, “Tota Pulchra,” first quarter of the 16th century, engraving, from a Parisian Book of Hours

This iconography of the Virgin surrounded by symbols has late medieval origins, appearing most notably in printed books of hours from the turn of the fifteenth century. However, it was taken to its height in Spain by the beginning of the seventeenth century as the definitive manner to depict the Virgin’s sinless conception.

Francisco de Zurbarán, The Immaculate Conception, 1628–30, oil on canvas, 128 x 89 cm (Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid); right: Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, The Immaculate Conception of Los Venerables (Soult Madonna), 1660–65, oil on canvas, 274 x 190 cm (Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid)

Murillo’s Virgins

What made Murillo’s versions so popular and successful? Unlike the formula established by his predecessors (such as Zurbarán or Pacheco), that includes over a dozen supporting allegorical elements and situates the scene within a recognizably earthly landscape, Murillo stripped the iconography down to its essence.

Guido Reni, The Immaculate Conception, 1627, oil on canvas, 268 x 185.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

He was undoubtedly influenced by the imported version by Italian painter Guido Reni, whose painting likely hung by the 1630s in the Cathedral of Seville, where Murillo could have closely studied it. Reni’s version is a radical simplification in which the Virgin appears between two angels overlaid on an almost depthless golden cloudscape, harkening back to a gilded icon.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, The Immaculate Conception of Los Venerables (Soult Madonna), 1660–65, oil on canvas, 274 x 190 cm (Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid)

Like Reni, Murillo removes the image to an entirely celestial sphere and crowds the canvas with adoring angels, leaving the moon as the only symbolic element. With this visual streamlining, he transforms the image of the contested theology into something instantly recognizable and viscerally understood. His Immaculate Conception became a rallying point for all defenders of the pious belief.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, detail of brushwork, The Immaculate Conception of Los Venerables (Soult Madonna), 1660–65, oil on canvas, 274 x 190 cm (Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid)

Beyond its edited iconography and carefully arranged composition, the work is also a masterpiece of technique. The chosen colors are rich and harmonious. In the Virgin’s gown, the artist demonstrates a masterful handling of whites, using greens, blues, and yellows to describe the folds and texture of the cloth. Boldly applied paint in the garment gives way to the hazy, almost vibrating brushwork seen in the Virgin’s head and the bodies of the cherubs, a seemingly effortless demonstration of the master’s mature style.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, detail of a portrait-like cherub, The Immaculate Conception of Los Venerables (Soult Madonna), 1660–65, oil on canvas, 274 x 190 cm (Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid)

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Self-Portrait, c. 1650-1655, oil on canvas, 107 x 77.5 cm (The Frick Collection)

The artist’s pride in this version of the Immaculate Conception over his other renditions is evident in its inclusion of a highly individualized, portrait-like cherub among the throng. The winged infant gazes directly at the viewer, its features a close match for those recorded in the artist’s self-portraits (such as ones in the Frick Collection or the National Gallery of Art), and—given the evident family resemblance—may in fact depict one of his eleven children.

The Hospital de los Venerables Sacerdotes

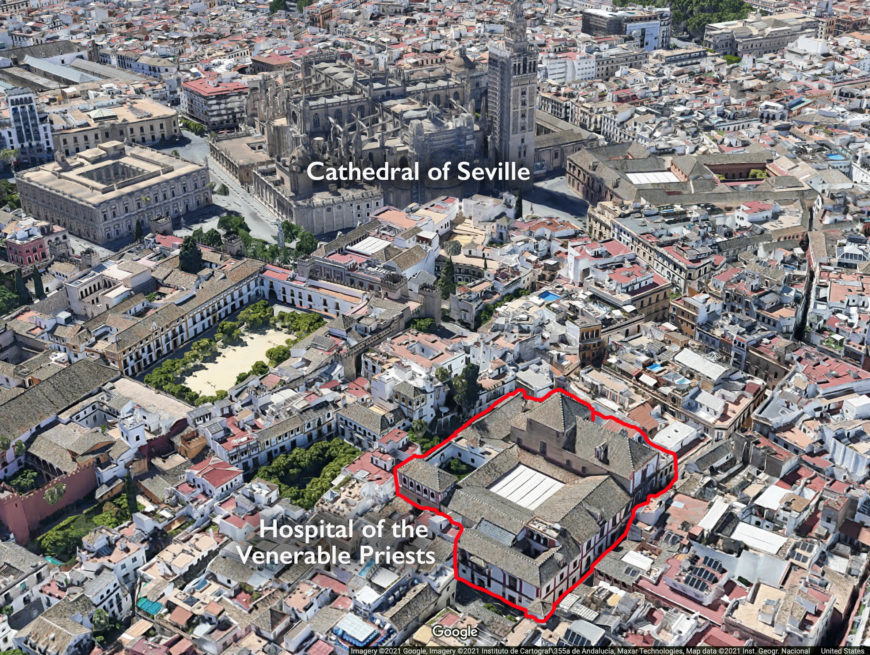

Of the many versions of the subject Murillo painted over the course of his decades-long career, this is without a doubt the most famous. Commissioned by the artist’s friend and patron Justino de Neve, it was destined for the latter’s private oratory and acquired after de Neve’s death for the newly inaugurated charitable foundation for retired priests known as the Hospital de los Venerables Sacerdotes (Hospital of the Venerable Priests) in Seville, which is located close to the city’s cathedral.

The Hospital’s establishment was part of a boom in charitable and pious construction in Seville in the wake of the devastating Great Plague of 1649, after which the city experienced a flourishing of the arts (even as its economic and political fortunes were in continual decline). Murillo’s painting hung in the Hospital until the early nineteenth century when it and other jewels of Seville’s artistic heritage were looted by Marshal Soult, Napoleon’s military governor in the region, and brought to France during the Peninsular War.

To France and back again

The picture, though to modern tastes perhaps saccharine in its earnest presentation of devotional content, was esteemed as one of the greatest of all time in the nineteenth century. It was auctioned in 1852, having been secured for the Musée du Louvre for the unprecedented price of 615,000 francs—at that point the highest price ever paid for a work of art.

Giuseppe Castiglione, The Salon Carré at the Musée du Louvre, 1861, oil on canvas, 69 x 103 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

The Immaculate Conception of Los Venerables, by then also known as the Soult Madonna (named after Napoleon’s governor in the Spanish region) was given pride of place in the museum, hung in the Salon Carré alongside works by other monumental artists such as Veronese, Raphael, Leonardo, Rubens, and Van Dyck, as recorded in the 1861 painting by Giuseppe Castiglione. Murillo’s painting is shown hanging in the gallery on the right side of the composition. French authors such as Honoré de Balzac and Émile Zola elegized Mary’s beauty. The work was incessantly copied by artists throughout the latter half of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries, as seen in a 1912 painting by Louis Béroud that shows a female artist replicating the Spanish artist’s works inside the Salon Carré.

In 1941, the picture left France for good, crossing the border as a gesture of goodwill between the Nazi-allied Vichy government and the Spanish dictatorship under Francisco Franco. It was installed in Madrid’s Museo Nacional del Prado the same year, where it remains to this day.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, The Immaculate Conception of Los Venerables (Soult Madonna), 1660–65, oil on canvas, 274 x 190 cm (Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid)

A cultural touchstone

The Immaculate Conception of Los Venerables is the most famous painting by the most acclaimed Spanish painter of the latter half of the seventeenth century. In it, the artist displayed his virtuosic skill and signature sweet style. It is a record of the power of images as a tool of persuasion, the ultimate triumph of the most successful visual campaign of the seventeenth century. The flood of images of the Virgin’s sinless conception led to a surge in popular support for the devotion and put continual pressure on the Vatican, helping pave the way for dogmatic definition two centuries later. It is a painting that, though less suited to twenty-first-century tastes, remained a cultural touchstone for centuries after it was painted. No mere record of straightforward piety, it is an artistic and persuasive triumph.

Additional resources:

The Immaculate Conception of Los Venerables at the Museo Nacional del Prado

The Restoration of The Immaculate Conception of Los Venerables, 2007

Jonathan Brown, “The Iconography of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception,” in Robert Enggass and Jonathan Brown, Italian & Spanish Art 1600–1750: Sources and Documents (Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 1992), 165–67

Suzanne L. Stratton, The Immaculate Conception in Spanish Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994)

Gary Tinterow and Geneviéve Lacambre, eds., Manet/Velázquez: The French Taste for Spanish Painting, exh. cat. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003)

Amanda Wunder, Baroque Seville: Sacred Art in a Century of Crisis (State College, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017)