A castle on colonial soil

The air feels humid with a thick layer of clouds covering most of the blue in the sky. Tall palms stand in unnaturally precise rows and shade a busy marketplace of exotic goods and colorfully dressed figures. The steep walls of a fort loom in the distance, dominating the horizon of the landscape. The fort is the so-called Castle of Batavia (in what is today Jakarta, Indonesia) that was built when the Dutch took control of the area in the seventeenth century. Like other Dutch landscape paintings of the period, such as Jacob Ruisdael’s View of Haarlem with Bleaching Fields, Andries Beeckman carefully arranged the elements of his canvas to highlight Dutch prowess and strength, especially in connection to the Dutch Republic’s ascension to colonial power in the seventeenth century. The Dutch occupied this city, as well as several others in Asia, for centuries (Indonesia only gained independence in 1949) and left traces of themselves in the architecture and other intangible colonial structures.

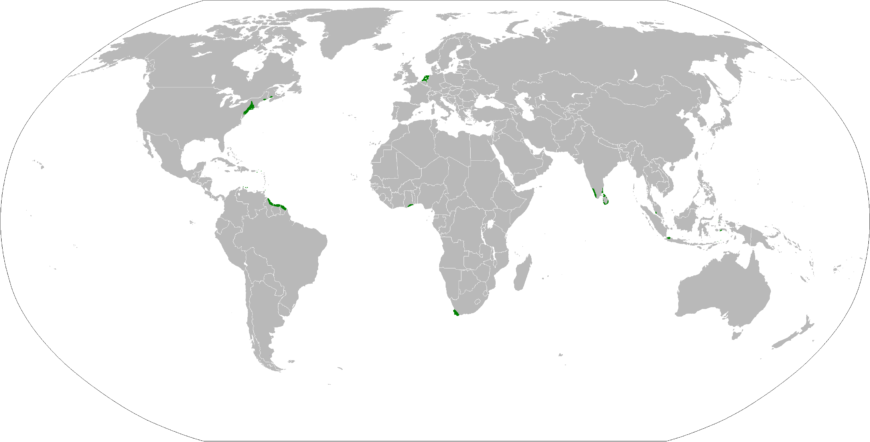

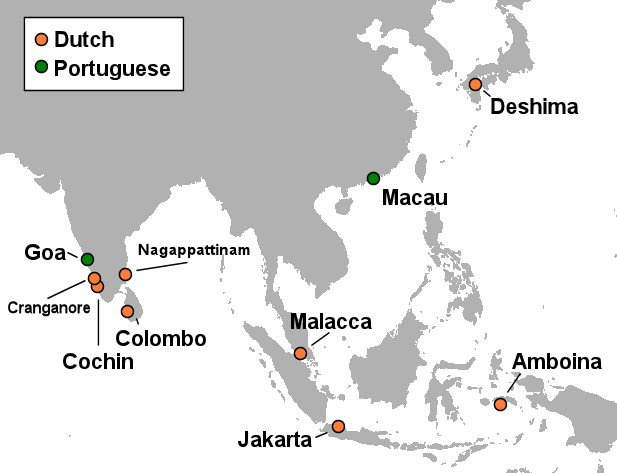

Map of some Dutch and Portuguese posts in Asia. The orange dots represent posts established by the Dutch East India Company, c. 1665

The VOC (Dutch East India Company)

The seventeenth century is often called the “Golden Age” of the Dutch Republic, and that is due in part to the trade produced by Dutch colonialism in Asia. The Dutch partially pirated the routes established by Portuguese traders in the sixteenth century. The fervor for Asian goods was sparked by the sale of cargo stolen in 1602 from a Portuguese ship, The San Tiago. That same year, six Dutch companies merged to create the Dutch East India Company (in Dutch, Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie; abbreviated as the VOC). The company was established to trade spices, but soon other profitable goods flowed from their docks and onto European luxury markets.

At its peak, the company had 40,000 employees from both European and Asian backgrounds and 600 posts in its charter area which extended from the Cape of Good Hope (at the southern tip of Africa) to Japan. These posts varied in size, languages, local culture, and trading opportunities. Some consisted only of a rented office and warehouse for the storage of goods; others included entire towns, shipyards, harbors, estates, plantations, schools, and hospitals all run by the VOC and local residents.

Pieter Isaacsz, Amsterdam as the Center of World Trade, lid of a harpsichord, c. 1604–1607, oil on panel, 79.4cm × 165cm × 3cm (Rijksmuseum)

The company was mandated to establish and maintain its monopoly over the Eastern waters and exercise its rule with almost absolute power. This power is celebrated in numerous forms from prints to the lids of musical instruments (such as one by Pieter Isaacsz. for the lid of a harpsichord) where the bounty of the world is laid at the feet of a personified city of Amsterdam who rests her hand on a globe, the “celebrated Global Trading capital . . . the sun and soul . . . of the entire planet.” [1]

Turning back to Indonesia, in 1612, Dutch soldiers razed the existing city of Jakarta and built a new city in its place. The reconstruction gave the Dutch complete control over the city’s structure and the day-to-day lives of its inhabitants. The VOC thereafter operated primarily from this eastern base which they named Batavia after the Batavians, a Germanic tribe that led a revolt against the Romans in 69 C.E. By selecting this name, the Dutch claimed a kind of ancestral ownership of the island, and the governor-general (the highest-ranking officer), ruled Batavia as if it were a sovereign state

The VOC commissioned The Castle of Batavia for their headquarters in Amsterdam, the capital of the Netherlands. Clearly an important function of the painting was to display the different categories of goods and people found in the Dutch colony.

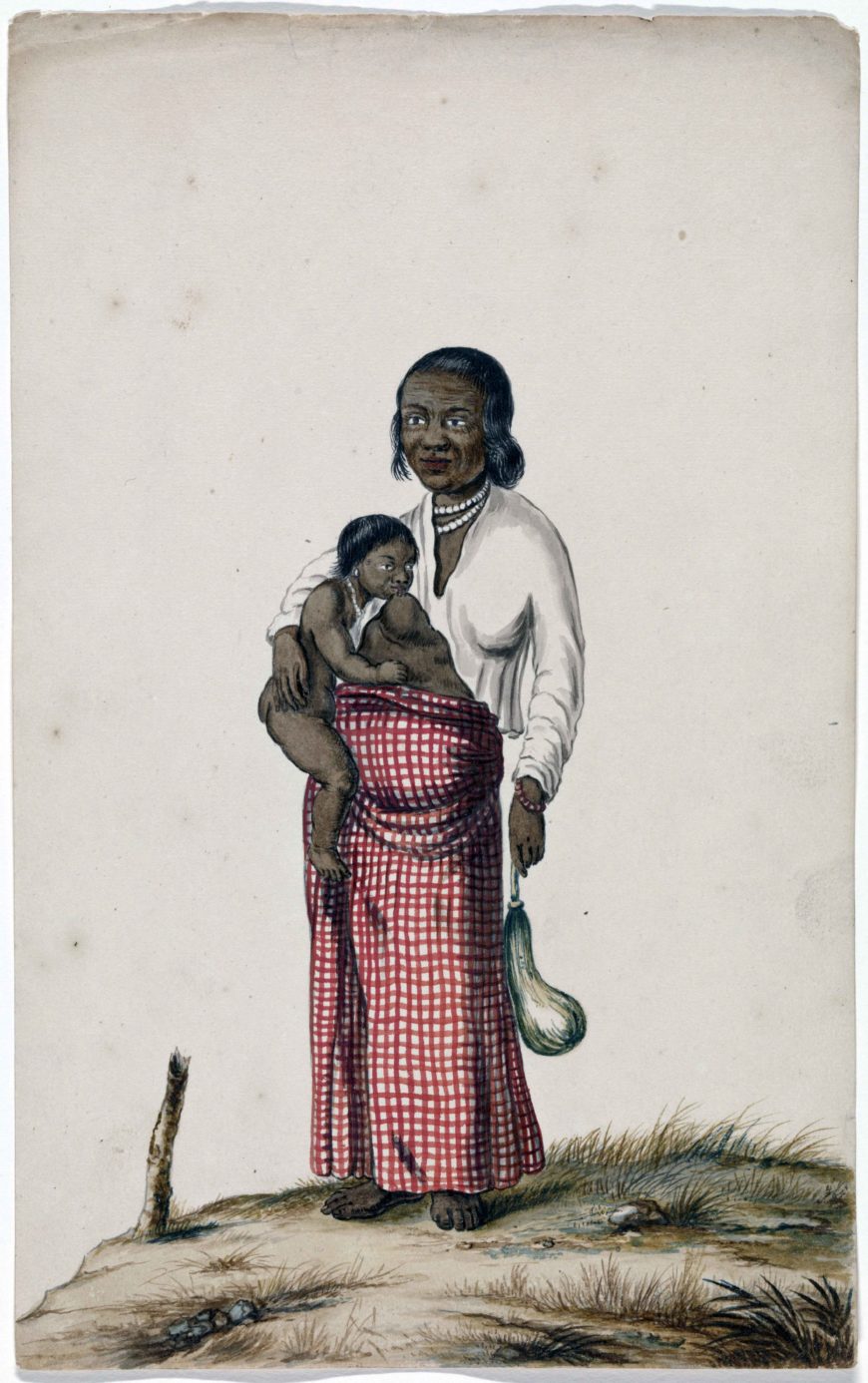

Andries Beeckman, detail of mother and child selling food, The Castle of Batavia, c. 1662, oil on canvas, 151.5 x 108 cm (Rijksmuseum)

The people of Batavia

In the sweeping landscape, the colorful gathering of figures in the foreground are overwhelmed by their surroundings. Andries Beeckman placed his viewer at an observable distance, possibly a nod to his background with the VOC. He worked for the VOC in Batavia from 1652 to 1658. While his official role is unknown, he created several drawings and sketches of his surroundings. Many of the figures in the marketplace, including the woman and her infant tending a fruit stand beneath the center row of palms, originate from Beeckman’s earlier sketches. The figures gathered in the marketplace give the viewer a glimpse into the diverse world of this important trading hub and what is today the capital of Indonesia.

Andries Beeckman, detail of the Castle of Batavia and soldiers, The Castle of Batavia, c. 1662, oil on canvas, 151.5 x 108 cm (Rijksmuseum)

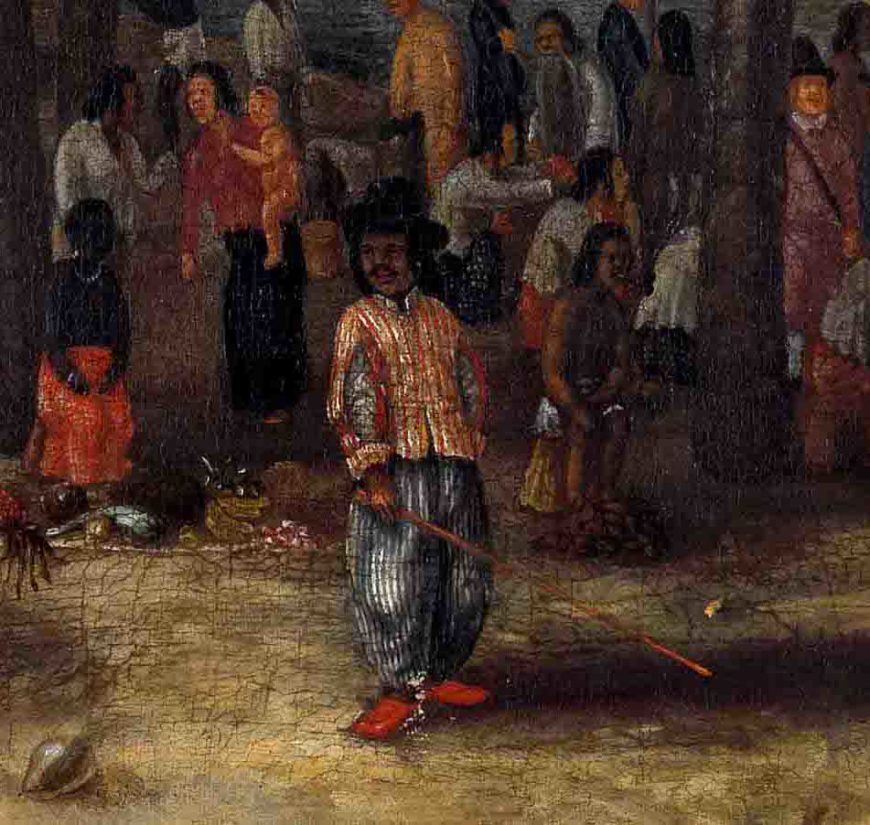

Clothing distinguishes the various social groups in Batavia, and Beeckman uses this system to great effect in his painting. Glancing across the vista, the viewer can see Dutch employees of the company and hired European soldiers riding in ranks from the Castle, wearing broad-brimmed hats and, comparatively dull, red and black clothing.

Andries Beeckman, detail of man wearing a black kimono (left), The Castle of Batavia, c. 1662, oil on canvas, 151.5 x 108 cm (Rijksmuseum)

Andries Beeckman, detail of man wearing a turban, The Castle of Batavia, c. 1662, oil on canvas, 151.5 x 108 cm (Rijksmuseum)

Moving into the marketplace a Dutch viewer could truly marvel at the culturally distinct attire worn by visiting merchants. A Japanese man is stepping away from a market stall on the far right corner in a flowing black kimono, and North African traders in white robes and turbans move gracefully beneath the trees. The representation of exotic attire intended to capture the imagination of Dutch viewers was utilized later by Albert Eckhout, an artist employed by the Dutch West India Company in Brazil. While Eckhout’s ethnographic studies were used to promote stereotypical notions of “the savage,” there is a romantic harmony in Beeckman’s work as the elaborately dressed traders, Europeans, and local Javanese peoples mingle beneath the palms and stalls teeming with tropical goods—with no indication of unrest or exploitation.

Andries Beeckman, detail of couple with a parasol, The Castle of Batavia, c. 1662, oil on canvas, 151.5 x 108 cm (Rijksmuseum)

Status symbols

Circle of Aelbert Cuyp, VOC Senior Merchant with his Wife and an Enslaved Servant, c. 1650–55, oil on canvas, 137.3 × 206.5 (Rijksmuseum)

In the central foreground Beeckman has placed a handsomely dressed couple, a Dutchman and his wife (who, based on her skin color and clothing, is of Asian or mixed heritage). Mixed marriages were common for lower-ranking officials as the company believed intermarriage was another tool of control and a means to ensure loyalty in the population. The Dutchman’s clothing seems to be made of blue Asian silks, a departure from the sober black attire consistent with traditional Dutch fashion and most official VOC portraits of the time. Dutch Batavians, much like the merchant in Beeckman’s painting, continued to display their wealth and status through ostentatious dress and behavior, creating a rank of pseudo-royalty in the colony.

Andries Beeckman, detail of a Mardijker in a striped shirt and pants, The Castle of Batavia, c. 1662, oil on canvas, 151.5 x 108 cm (Rijksmuseum)

One of the most important elements for displaying this royal intention was the parasol, a symbol usurped from the local culture. Javanese rulers were the only ones permitted to use the parasol before the arrival of Europeans. In European art of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, the parasol became inextricably linked to imaginatively exaggerated ideas surrounding “Eastern” cultures and appears quite frequently in Orientalist artworks and decorations. The parasol, on the one hand, was practical and protected people from the harsh tropical sunlight, and on the other functioned as a status symbol, an aspect underscored by the presence of the enslaved person who is holding the parasol over the couple.

Slavery was commonplace in Asia (and elsewhere) at this time, and the VOC continued and contributed to that practice—making Batavia an active slave market. In his romanticized vision, Beeckman shows his viewers a minimal glimpse into this brutal practice with the the figure clutching the parasol as well as through the depiction of descendants of freed slaves, or as the VOC dubbed them Mardijkers. This social group was descended from enslaved people in South India or Bengal (areas under Portuguese control), and are identified by their striped shirts and stripped pants (see for example, the man in the foreground toward the right edge of the market).

Andries Beeckman, detail of the Castle of Batavia and canal, The Castle of Batavia, c. 1662, oil on canvas, 151.5 x 108 cm (Rijksmuseum)

Colonial structures

The built environment of Batavia shaped the city’s hierarchy and served the needs of the VOC. Architects codified segregation into the design of the city plan, primarily in the form of unbridged canals, such as the one cutting through the center of the painting thus effectively separating the diverse marketplace from the seat of government. These structures subtly subvert the inhabitants and enforce Dutch rule.

Architecture also played a subtle role in dominating the population of Batavia. Beeckman’s Castle looms above the native, thatched structures hugging the shore of a man-made canal. Inside the walls of the imposing fort are sun-drenched steeped-roof structures that mimic native Dutch architecture. This enclosed and illuminated city is yet another subtle indication of the strength, and possibly divine consent, of the Dutch on foreign soil. In many European paintings, light is often used to imply a connection between the illuminated figure or structure and the divine.

A demonstration of power

Andries Beeckman’s Castle of Batavia is a figurative demonstration of the dominating power of the Dutch East India Company in Batavia and, unquestionably, their entire trade region in the seventeenth century. The Dutch castle looms on the horizon and the high-ranking Dutchman shaded by a parasol holds the center, showing the total occupation of the Dutch in this Southeast Asian city.

Notes:

[1] This quote is from a legend, printed beneath Claes Jansz Visscher Profiel van Amsterdam, gezien vanaf het IJ (1611)

Additional resources

See this painting on the Rijksmuseum website

Janet C. Blyberg, Asia in Amsterdam: The Culture of Luxury in the Golden Age. Edited by Karina Corrigan, Jan van Campen, and Femke Diercks (New Haven, Conn: Peabody Essex Museum, 2015)

Marten Jan Bok, “European Artists in the Service of the Dutch East India Company.” In Mediating Netherlandish Art and Material Culture in Asia, edited by Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann and Michael North (Amsterdam Studies in the Dutch Golden Age. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2014)

Jan van Campen, “The Hybrid World of Batavia.” In Asia in Amsterdam: The Culture of Luxury in the Golden Age, edited by Karina Corrigan, Jan van Campen, Femke Diercks, and Janet C. Blyberg (New Haven, Conn: Peabody Essex Museum, 2015)

Martine Gosselink, “The Dutch East India Company in Asia.” In Asia in Amsterdam: The Culture of Luxury in the Golden Age, edited by Karina Corrigan, Jan van Campen, Femke Diercks, and Janet C. Blyberg (New Haven, Conn: Peabody Essex Museum, 2015)

Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann and Michael North, eds., Mediating Netherlandish Art and Material Culture in Asia. Amsterdam Studies in the Dutch Golden Age (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2014)

Marsely L. Kehoe, “Dutch Batavia: Exposing the Hierarchy of the Dutch Colonial City,” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 7, no. 1 (Winter 2015)