Detail, Anthony van Dyck, Charles I with M. de St. Antoine, 1633, oil on canvas, 370 x 270 cm (Queen’s Gallery, Windsor Castle)

Horsepower

Equestrian portraits (a figure on a horse) are usually reserved for military and political leaders, following an ancient tradition going back at least as far as Alexander the Great and the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius. A horse is essentially a pedestal upon which leaders can elevate themselves above the common people, but the equestrian format is also a metaphor for taming and training nature: an indication of the potential of the rider to guide the populace and subdue external enemies.

Charles I, King of England was particularly in need of these kind of symbolic associations as he was not physically prepossessing (his adult height was just 163cm (5 feet 4 inches) and he suffered from a speech impediment), nor was his rule glorious (he was eventually beheaded after a long and costly civil war). Charles I with M. de St. Antoine was the first equestrian portrait ever painted of this king, and Anthony van Dyck purposefully chose this format to enhance Charles’s status at a particularly unstable moment in British history.

Anthony van Dyck, Charles I with M. de St. Antoine, 1633, oil on canvas, 370 x 270 cm (Queen’s Gallery, Windsor Castle)

A clear message

Charles I is riding a white horse towards us, through a triumphal arch. Van Dyck has used the architecture to provide compositional structure, splitting the scene into three vertical sections, and positioning a key element in each: a coat of arms, the king, and a figure dressed in red. Together they create a roughly pyramidal form with the king’s head at the apex. However, the simplicity of layout has been animated with the addition of some billowing green drapery, and the movement of the human and animal figures — especially the foreshortened body of the horse as it steps forwards, its front hoof touching the edge of the picture plane.

Coat of arms and foreshortened horse (detail), Anthony van Dyck, Charles I with M. de St. Antoine, detail, 1633, Oil on canvas, 370 x 270 cm (Queen’s Gallery, Windsor Castle)

Authority to rule and a supreme military leader

Each of the ancillary elements of the painting contains additional information that contributes to the overall message of Charles’s authority to rule. The royal coat of arms, for example, contains the insignia of England (three lions), Scotland (lion rampant) and Ireland (harp), to show the unification of the nations of the United Kingdom (England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales) under the rule of Charles’s father James I.

Anthony van Dyck, Charles I with M. de St. Antoine, detail, 1633, Oil on canvas, 370 x 270 cm (Queen’s Gallery, Windsor Castle)

The figure dressed in red is Pierre Antoine Bourdin, Seigneur de St. Antoine, an expert riding master who had been sent to Charles by the King of France as a diplomatic gift, along with six thoroughbred horses. St. Antoine’s reverential and subservient gaze further enhances the King’s mystique in our eyes, but perhaps also symbolizes England’s longed-for pre-eminence over her European neighbor.

Anthony van Dyck, Charles I with M. de St. Antoine, detail, 1633, Oil on canvas, 370 x 270 cm (Queen’s Gallery, Windsor Castle)

However van Dyck’s most significant message about Charles is his supremacy as a military leader. The presence of a triumphal arch – a structure built to celebrate and commemorate victories in ancient Rome – implies that this English King is the natural heir to the triumphant emperors of the classical past.

Charles’s highly polished armor and baton of command compound this message, as does the blue sash around his chest and medallion at his hip, which shows him to be a member of the Order of the Garter, the most prestigious knighthood in England. Thus, Charles is appropriating the iconography of medieval knights-errant, as well as classical rulers, in order to appeal to his audience’s sense of history.

The Baroque arrives in England

King Charles I was a great lover of the arts, and during his reign he amassed an unrivaled collection of European Renaissance paintings and sculptures. He was just as much a fan of the more up-to-date Baroque style, with its dynamic compositions and psychological intensity, and so he acquired works by Caravaggio, Peter Paul Rubens, and Gianlorenzo Bernini among many other Baroque artists.

Charles’s main coup was employing the Flemish artist Anthony van Dyck as his official court painter in 1632. Charles I with M. de St. Antoine was commissioned to be hung in the King’s gallery at St. James’s Palace in London, and it was certainly intended to compete with the other Renaissance and Baroque paintings on display. Its scale is vast — the dimensions more usually associated with tapestries — and it was probably hung at the end of a long corridor, creating the illusion of an aperture in the palace walls and a view onto a vista beyond.

Armada Portrait of Elizabeth I, formerly attributed to George Gower, 1588, oil on oak panel (Woburn Abbey)

In comparison to previous portraits of English monarchs such as Elizabeth I’s Armada Portrait, van Dyck’s work is rich in color, replete with observed detail, and possesses a Baroque sense of movement and grandeur. It shows that Charles I was on-trend, learning from other European images of power, such as Peter Paul Rubens’s 1603 Equestrian Portrait of the Duke of Lerma, and aiming to lead English artistic tastes along continental lines.

Left: Anthony van Dyck, Charles I with M. de St Antoine, 1633, oil on canvas, 370 x 270 cm (Queen’s Gallery, Windsor Castle); right: Peter Paul Rubens, Equestrian Portrait of the Duke of Lerma, 1603, oil on canvas, 290.5 x 207.5 cm (Museo del Prado)

A political statement

This progressive attitude to the arts came at a political cost. Charles’s critics in England saw the king’s interest in foreign styles as evidence of his softening attitudes to Catholic sensibilities (England had broken from the Catholic church a hundred years earlier during the Protestant Reformation), and his court’s ideological detachment from the rest of the nation. These clashes contributed to Parliament’s animosity towards the crown, which in turn led to the English Civil War (1642–51).

In the years leading up to the civil war, Parliament frustrated the king’s military ambitions by curbing his ability to raise money through taxation. In 1629 Charles retaliated by dissolving Parliament and governing the nation independently in an eleven-year period of “personal rule.” Charles I with M. de St. Antoine, painted during this period of autocracy, encapsulates the King’s notion of independent authority, and his belief in the divine right of kings (the notion that God had sanctioned his right to rule). Indeed, there is something saintly about the depiction of Charles in this painting, judging by his pristine white horse and the awed expression of the Seigneur de St. Antoine. Perhaps the courtly audience of this painting may have seen Charles as a modern embodiment of St. George — the dragon-slaying patron saint of England who was typically represented as a valorous knight.

Legacy

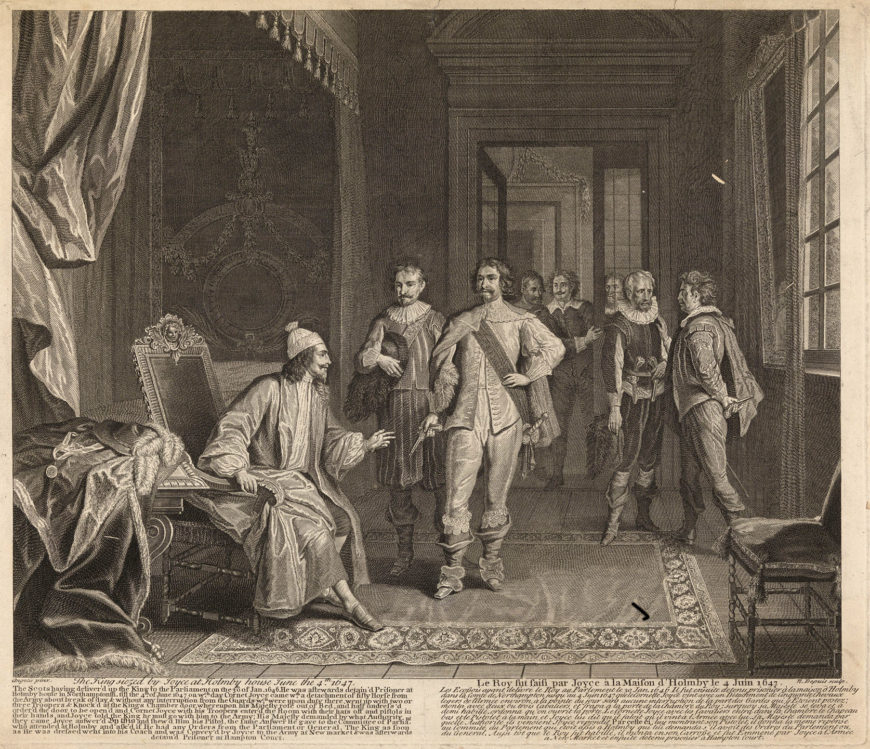

Nicolas-Gabriel Dupuis, The King siezed by Joyce at Holmby house June the 4th, 1647, c.1728, engraving, 41.2 x 49.4 cm (Royal Collection Trust)

After the Parliamentarians won the English Civil War, Charles I was put on trial, found guilty of treason, and condemned to be beheaded. In the aftermath England became a republic and many of Charles’s possessions (including his extraordinary art collection), was sold off to raise funds for the new political regime. Charles I with M. de St. Antoine went to an Englishman named Hugh Pope for £150. However the royal family was re-instated in England later in the seventeenth century and they quickly bought back the painting. It remains in the royal collection to this day.

Meanwhile, van Dyck’s fluid, sensuous style of portraiture has had a lasting effect on English art, emulated by many of the nation’s greatest portrait painters including Thomas Gainsborough, Thomas Lawrence, and the American expatriate John Singer Sargent.

Additional resources

This painting at the Royal Collection Trust

Read more about Rubens and van Dyck at the Metropolitan Museum of Art