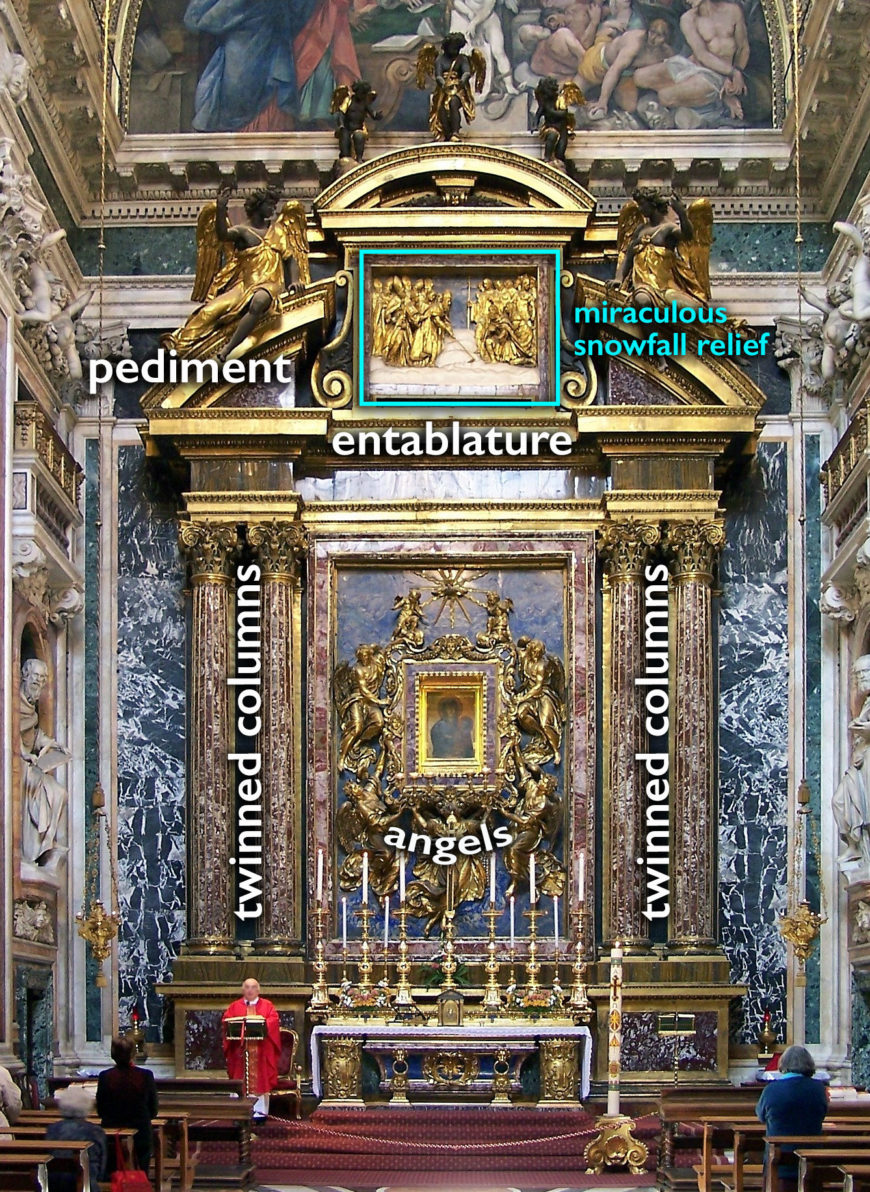

Altar Tabernacle, Pauline Chapel, Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome, completed 1612 (photo: Berthold Werner)

An icon and its packaging

We all get annoyed by excessive and wasteful packaging that dwarfs, and ultimately cheapens, the product that it contains. The altar tabernacle at the Pauline Chapel (commissioned by Pope Paul V) at Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome certainly has a lot to behold. But in this case, the packaging functions effectively to broadcast the importance of the tiny object within. This huge and extravagant Baroque confection serves as the frame for one of the most important religious artifacts in Rome: an icon of the Virgin and Child believed at the time to have been painted by Saint Luke. Medieval tradition maintained that Saint Luke was the first Christian painter, and made a number of portraits of the Virgin and Child from life. Though this Byzantine icon is certainly not old enough to date from the time of Christ, scholars remain unsure exactly when it was produced, and have suggested dates ranging from the fifth to thirteenth centuries. Its nickname, the Salus Populi Romani (roughly “Savior of the People of Rome”), signifies its role as divine protector—it was used in medieval rituals staged to ensure the city’s safety and wellbeing. Its installation in this altar in the early 1600s reveals the high esteem with which this image was regarded in the seventeenth century.

Salus Populi Romani, Pauline Chapel, Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome (photo: Fr Lawrence Lew, O.P., CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The icon

Salus Populi Romani, after restoration in 2018, Pauline Chapel, Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome (photo: SeoulKing, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Salus Populi Romani icon of the Virgin and Child at the center of the altar tabernacle of the Pauline Chapel is typical of Byzantine icons, which were used to facilitate prayer to the figures represented. The Virgin Mary looks outward in a simple, frontal presentation. The infant Christ looks up at her while grasping a book with one hand and holding the other in a gesture of blessing. Both are relatively flat with elongated and heavily outlined facial features, large almond-shaped eyes, and wrinkled drapery. They are set against a gold background that places them in a transcendent and luminous setting that lends them a divine aura. Above the Virgin Mary are Greek letters that identify her as the Mother of God.

This icon has an illustrious history that explains why it came to be embedded amongst such rich material splendor. It is one of a number of icons in Rome that were believed to have been painted from life by Saint Luke. This attribution gave it the authority of a portrait conveying the true likenesses of Christ and his mother.

This icon in particular marked the city of Rome as a sacred place, and it was credited with protecting the city from the plague in the sixth century. It featured in a ritual procession that took place every year on August 15th during the Feast of the Assumption. A miraculous icon of Christ at the Sancta Sanctorum was processed through the city and delivered to the church of Santa Maria Maggiore, where it would meet the Salus Populi Romani icon. The bringing together of these two icons was understood as the encounter of Christ and his mother represented in them. Sacred rituals like these were staged to ensure that the holy figures, through their icons, would continue to work miracles and protect the citizens of Rome from a host of threats.

The Pauline Chapel in Santa Maria Maggiore (© Google Street View)

The chapel

The Pauline Chapel owes its existence to the renewal (in the 17th century) of one of the earliest and most important Christian churches in Rome, and indeed the very first one dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Legend maintains that Santa Maria Maggiore was built on the site of a miraculous snowfall in the fourth century. It has a simple basilica plan consisting of a wide central nave flanked by side aisles. It was originally richly decorated in mosaics—some of the oldest of which, from the fifth century, can still be seen lining the nave arcade and in the archway framing the apse. Starting at the end of the 1500s the basilica underwent extensive renovation. It was during this time that Pope Sixtus V built the Sistine Chapel on the right side of the nave to house a reliquary containing the Holy Crib. Pope Paul V added the Pauline Chapel on the left side of the nave (consecrated in 1613) to house the icon of the Virgin and Child.

Interior of Santa Maria Maggiore, looking down the nave toward the altar. The Pauline Chapel is on the left side of the nave (photo: Livioandronico2013, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The interior of the Pauline Chapel radiates color and light. It is lavishly adorned with luminous colored marble paneling, gold leaf, lively sculptures, and enormous painted frescoes in the lunettes, pendentives, and in dome above. But amidst this visual opulence, the focal point is the monumental altar tabernacle housing the inset icon of the Virgin and Child, which would otherwise be dwarfed inside this densely decorated chapel.

Altar Tabernacle, Pauline Chapel, Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome, completed 1612 (photo: Berthold Werner)

Baroque extravagance

The designers of this tabernacle, Girolamo Rainaldi and Pompeo Targone, based the frame on classical architecture. It is essentially a full-size classical temple façade with columns supporting an entablature and pediment. It is similar to the architectural language of the classicizing Italian Renaissance that sought to renew the order and grandeur of ancient Rome. But here, in typical Baroque fashion, both the materials and the formal design have been enlivened with the express purpose of exciting the viewer’s gaze towards the celebrated icon and the sacred power that flows from it.

Annotated Altar Tabernacle, Pauline Chapel, Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome, completed 1612 (photo: Berthold Werner)

Everything is fashioned out of richly veined colored marble detailed in gold leaf. A relief sculpture showing the miraculous snowfall that christened the founding of the church splits the summit of the tabernacle’s rounded pediment. The gilded and fluted supporting columns have been twinned on either side of the inset icon. They act as theater curtains that have parted to reveal the miraculous image of the Virgin and Child. Traditionally, cult images were concealed behind veils that could be drawn back in calculated spectacles of display during religious rituals. The architecture of the Pauline Chapel essentially performs that spectacle in perpetuity. In so doing, it offers a dynamic theatricality that is typical of the sort of Baroque art in Italy that aimed to excite the viewer.

Salus Populi Romani, Pauline Chapel, Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome (photo: Fr Lawrence Lew, O.P., CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The scene revealed by the gilded columns consists of a ring of golden angels carrying the icon against the blue background of an expensive stone called lapis lazuli, signifying the heavenly realm in which Mary and Christ reside. This composition casts the icon into a narrative of Mary’s Assumption, when her virgin body, pure and without sin, rises upward to enter into heaven.

Triumph

The altar tabernacle of the Pauline Chapel at Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome repackages a medieval icon and turns it into a dazzling Baroque trophy. In this way it shows how Baroque architectural design could reflect the triumphant mood of the Christian church. After withstanding an onslaught of Protestant criticisms during the Reformation in the sixteenth century, Catholics reaffirmed their belief in the power and spirit of sacred images during the Council of Trent. They did so by staging dramatic spectacles of display, like this one, that excite the viewer’s eyes and ignite spiritual devotion to objects regarded as holy. The resplendent setting of this tabernacle affirms belief in the authority of the icon as a powerful mediator between Mary and the faithful and in the truth of its miraculous powers. These Baroque theatrics give material and visual expression to the outsize aura of divinity that radiates from it. If only all forms of packaging were this effective!