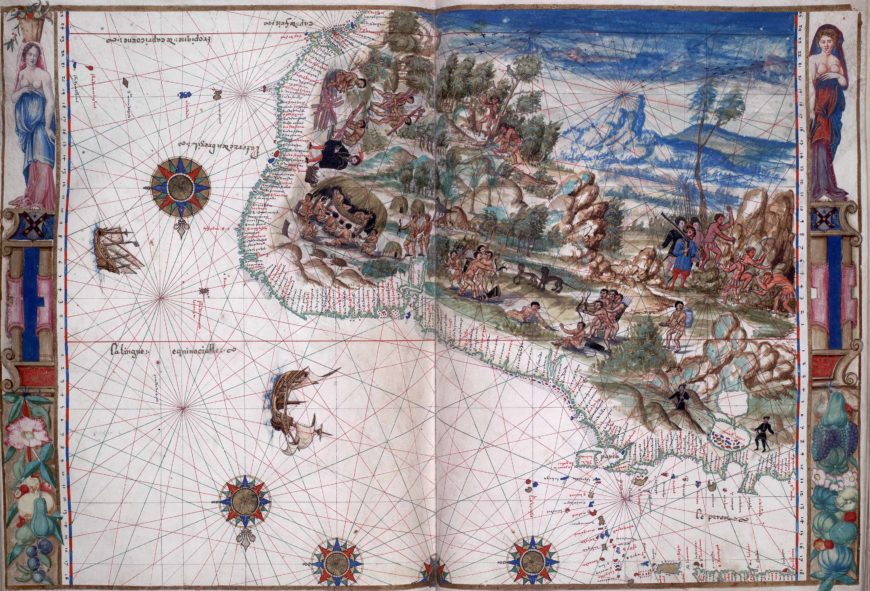

“Northeastern South America” in the Vallard Atlas, c. 1547, folio 11 (Huntington Library; photo UC Berkeley Library, www.digital-scriptorium.org, CC BY-NC 4.0).

Although news of Christopher Columbus’s “discovery” of the Americas had already spread across Europe, the Portuguese stumbled upon Brazil by accident. In 1498, Vasco da Gama successfully sailed from Portugal around the southern tip of Africa to India, achieving what Columbus had hoped to accomplish: establishing an overseas route between Europe and Asia. In 1500, Pedro Alvares Cabral set out from Portugal to replicate da Gama’s journey to India but veered too far west and landed instead on the shores of Brazil. Although Cabral’s team only stayed in Brazil for a few days before continuing on to India, they sent a letter to the Portuguese king to inform him of the discovery. The letter describes peaceful exchanges with naked indigenous peoples who hunted with bows and arrows and slept in hammocks.

This atlas shows native Brazilians bringing brazilwood to a French merchant dressed in black. “Northeastern South America,” detail of French merchantå in the Vallard Atlas, c. 1547, folio 11 (Huntington Library; photo UC Berkeley Library, www.digital-scriptorium.org, CC BY-NC 4.0).

The Portuguese colonization of Brazil was initially quite different from the Spanish conquest of the Americas. The Portuguese were more invested in evangelization and trade in Asia and Africa, which included trafficking in enslaved humans, and viewed Brazil as a trade post instead of a place to send larger numbers of settlers. Unlike the extensive stone-built cities of Mesoamerica and the Andes, indigenous inhabitants of Brazil lived in villages. Rather than launching large military campaigns to conquer empires, the Portuguese engaged in trade with native Brazilians and smaller-scale battles against rival groups. Brazil’s first export to Europe was brazilwood, a tree that produces a red dye and that gave the region its name. Wanting access to brazilwood, the French also created alliances with indigenous groups and competed over control of Brazil for much of the sixteenth century. The French Vallard Atlas shows native Brazilians bringing brazilwood to a French merchant dressed in black. The feather skirts are likely a misinterpretation of headdresses.

Converts and Cannibals

Portuguese explorers believed that native Brazilians would be easily converted to Catholicism once the language barrier had been overcome. Franciscan and Jesuit missionaries rushed to Brazil and lived with converted indigenous peoples in aldeias (villages) separate from the towns and cities where Portuguese settlers lived. Even though the Pope had forbidden enslavement of Native Americans in 1537, explorers called bandeirantes traveled about capturing native Brazilians to sell into slavery. As in the Spanish Americas, some missionaries helped to protect indigenous communities from enslavement, while others exploited indigenous labor.

“Native Americans kill and eat a prisoner,” fold-out plate engraving, 18.4 cm, in Naaukeurige versameling der gedenk-waardigste zee en land-reysen na Oost en West-Indiën … zedert het jaar 1524 tot 1526 (Leiden: Pieter van der Aa, 1706), vol. 15, part 1, p. 56 (John Carter Brown Library)

The letter that announced the Portuguese arrival in Brazil described native inhabitants as complacent and harmless, but later accounts by adventurers and missionaries focus heavily on the practice of ritual cannibalism. Although there is little evidence that indigenous cultures practiced cannibalism, rumors of such actions were viewed as a justification for enslavement. The association of native Brazilians with cannibalism has had a lasting effect on the arts even into the twenty-first century. Tarsila do Amaral’s painting Antropofagia (based on the Greek word for cannibalism) is a particularly famous example.

Map of Brazil in 1644, showing Dutch and Portuguese territories (source: Carl Pruneau, CC BY 3.0)

From Sugar to Gold

Sugar soon overtook brazilwood as the colony’s most important industry. Europeans forced enslaved Africans to work on sugarcane plantations, providing plantation owners with great wealth. The sugar industry attracted the Dutch, who gained control over the northeast of Brazil from 1630 to 1654. Although short-lived, the Dutch colony produced a substantial number of artworks. The governor Johan Maurits van Nassau was a supporter of scientific exploration. His palace in the capital Mauritsstad (Recife) included botanical gardens and a zoo, and he brought two Dutch painters, Albert Eckhout and Frans Post, with him to document the flora, fauna, and customs of Brazil. The merchant and painter Zacharias Wagener, who had been serving military duties in Brazil, also joined the governor’s court.

Frans Post specialized in landscape painting and continued to produce depictions of Brazil such as this one after returning to Europe. Frans Post, Brazilian Landscape with Anteater, 1649, oil on canvas 52.8 x 69.3 cm (Alte Pinakothek, Munich, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Once the Portuguese had expelled the Dutch, they continued to settle Brazil’s vast territory and exploit its resources. In addition to enslaved Africans producing sugar in the Northeast, explorers found gold and diamonds in an inland region called Minas Gerais (General Mines). The abundant gold and diamonds, mined by enslaved individuals, allowed wealth, trade, and artistic production to flourish in the entire Portuguese empire throughout the eighteenth century. As the closest port to the mining region, Rio de Janeiro was named Brazil’s new capital city in 1763.

Google Map of Church of Our Lady of the Rosary in Recife in BrazIl

Afro-Brazilians as Artists and Patrons

More enslaved Africans were transported to Brazil than to any other region of the Americas. As a result, Brazil’s economy, built environment, and culture are founded on the activities of Africans and people of African descent. Not only were most colonial architectural projects built by enslaved individuals, but some of the most famous artists of colonial Brazil were also people of African ancestry. Antonio Francisco Lisboa, known by the nickname Aleijadinho (Little Cripple), was a sculptor in Minas Gerais, and Valentim da Fonseca e Silva, or Mestre Valentim, was an architect who worked in Rio de Janeiro. Afro-Brazilians were also active patrons of the arts. Both enslaved and free people of color joined confraternities to celebrate Catholic saints. Confraternity members pooled their resources and commissioned churches where they held religious services. Churches belonging to Afro-Brazilian communities survive all over Brazil, such as the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary in Recife (as seen above).

Portal of the Academy of Fine Arts, Rio de Janeiro, now in the botanical gardens. The rest of the academy was demolished in 1938 (photo: Rodrigo Soldon, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

An Unusual Ending

In 1807, Napoleon’s army invaded Portugal and the Portuguese royal family fled to Rio de Janeiro. This move transformed Rio de Janeiro into the capital of the Portuguese Empire and dramatically altered the political, economic, and cultural landscape of Brazil. The Portuguese king invited several French artists to Rio de Janeiro (this group is called the French Artistic Mission) who were tasked with the creation of the Academy of Fine Arts. The royal family returned to Portugal in 1821, but the king’s son Pedro I remained in Brazil. The following year, Pedro declared independence and named himself emperor of Brazil.