Seated Buddha with Two Attendants, c. 132 C.E., Kushan period, from Mathura, red sandstone, 36 5/8 x 33 5/8 x 6 5/16 inches (Kimbell Art Museum)

Seated Buddha with Two Attendants is an early example of the Buddha shown in anthropomorphic (human) form. The historic Buddha, born a prince named Siddhartha Gautama, is believed to have lived and preached in the fifth century B.C.E. When he died, his relics and the stupas that came to symbolize the Buddha became the primary focus of devotion for his followers.

Great Stupa at Sanchi, 3rd c. B.C.E.–1st c. C.E., Sanchi, Madhya Pradesh (photo: AyushDwivedi1947, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Buddha was not shown in human form in early Indian art, but rather, in aniconic (symbolic) form. Stupas were adorned with visually engaging stories that celebrated the Buddha with symbols—footprints, thrones, and parasols, for example—that signified the presence of the Buddha and commanded the respect that the Buddha himself would receive.

The reasons for avoiding anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha in those early centuries may have centered on the belief that the Buddha—who had lived 550 lifetimes and had achieved nirvana (liberation from the cycle of karmic rebirth)—was freed of the human form. By the turn of the common era, however, Buddhist beliefs had changed. The Buddha was deified, and with the development of the anthropomorphic Buddha, devotees were given a new focus for their ritual practices in shrines and monasteries.

Seated Buddha

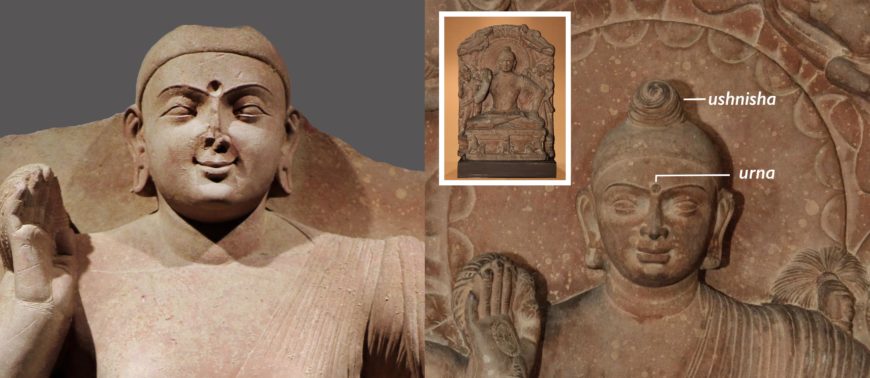

Smiling, the Buddha sits cross-legged and rests a closed fist on his left knee. Layers of cloth gathered on his left arm and shoulder fall gracefully down his back, while the curved indentation across his chest and across his calves suggests the lightness of his robe. The Buddha holds his right hand up in abhaya mudra—a gesture of protection and reassurance. Wheels (marked on the palm of his hand and on his feet) and lotuses on his feet announce the Buddha’s divinity. Other signifiers of his godliness, such as the ushnisha (cranial protuberance, see image below) and urna (auspicious mark on the forehead) have been lost over time. The ushnisha would have been covered by a tightly twisted hair–bun and centered above the Buddha’s head, while the urna was likely once a small rock crystal. The historic Buddha’s life as a prince prior to his enlightenment is referenced by his elongated ears, which were caused by the heavy jewelry that he once wore.

To visualize the lost ushnisha and urna on the Seated Buddha with Two Attendants (left), 132 C.E. (Kimbell Art Museum), we can compare it with another early Buddha image, the Katra stele (right), end of the 1st century C.E. (Government Museum, Mathura) (photo: Biswarup Ganguly, CC BY-3.0)

Although the mottled red color of the stone in the Seated Buddha is striking, our attention is focused on the sculptors’ meticulous carving. A close look at the Buddha shows carefully outlined fingers on his left hand and a beautifully detailed thumb and fingernail, a realistic portrayal of the knees and wrists, and a softly modeled stomach. The face is also particularly compelling, and we can almost see the Buddha’s chin lift as he smiles.

The Buddha’s Attendants

Gods and goddesses in Indian art are often accompanied by attendants, and here the Buddha has two. The artists have employed a technique known as hierarchic scaling to emphasize the Buddha’s importance because the smaller scale of the attendant figures highlights his monumentality. Imagine how the Buddha would tower over his attendants if he were to stand! The attendants mirror one another in their stances and adornment, and they both carry a chauri (fly-whisk) in their right hand in a gesture that indicates their service to the Buddha. Subtle differences in their facial features and in their headdresses suggest individual personalities.

Seated Buddha shown with approximate halo (Kimbell Art Museum) and Stele with Bodhisattva and Two Attendants, c. 2nd century C.E., red sandstone, 7 5/16 x 8 7/16 x 2 3/4 inches (Harvard Art Museums)

This type of representation of the Buddha appears to have been popular in the second century C.E. Comparing the Seated Buddha to similar stelae from the same period helps us determine its missing parts. Looking at a stele known as the Katra stele (after Katra, an archaeological site in Mathura, India) and another titled Stele with Bodhisattva and Two Attendants in the collection of the Harvard Art Museums, we can see that the upper portion of the Seated Buddha may have once had a large halo and flying celestial beings. Halos (referencing rays of light) and celestial beings signify divine radiance and the attendance of a heavenly retinue.

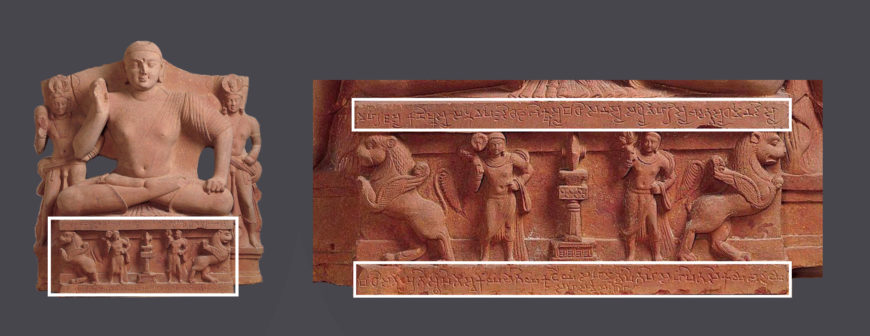

Detail of relief panel (highlighted) and inscription on the dais, Seated Buddha (Kimbell Art Museum)

Inscriptions and dates

On the face of the carved dais are rampant leogryphs and a pair of attendants who flank a pillar. The Buddhist character of the pillar is evident by the wheel (the wheel symbolizes the Buddha’s teachings) that is shown in profile at its summit. The pillar and the wheel represent the Buddha and his teachings, and are flanked by attendants just as the figure of the Buddha is above.

The relief panel is framed by two lines of text in Sanskrit. [1] Inscriptions such as these record donors’ gifts for posterity and include the date of the donation. These dates followed the regnal years of the king who was in power at that time. The inscription on the Seated Buddha mentions the dedication of the image during the fourth year of the Kushan dynasty (c. 2nd century B.C.E.—3rd century C.E.) king Kanishka. Although scholars continue to refine the year in which Kanishka ascended the throne, the current consensus suggests that the image would have been dedicated in c. 132 C.E. Seated Buddha is one of only a few Buddha images that has been dated with an inscription to this early period in the common era. Having this frame of reference is invaluable because it helps scholars date stylistically similar images to this period.

Gandhara and Mathura

The sandstone from which Seated Buddha was carved was preferred by the artist workshops of Mathura, a city in northern India. Mathura and the Gandhara region (in present-day Pakistan) have yielded the earliest known anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha. Both Gandhara and Mathura were under the rulership of the Kushan kings at the turn of the common era and were important political centers; the Kushans’ winter capital was located in Mathura and their summer capital in Gandhara.

A comparison of Buddhas from Mathura and Gandhara. Left: Katra stele, Government Museum, Mathura (photo: Biswarup Ganguly, CC BY-3.0); right: The Buddha, c. 2nd–3rd century C.E., from Gandhara, schist, approximately 37 x 21 x 9 inches (The British Museum). Note the differences in the style of the Buddhas’ hair, robe, and drapery.

Gandhara Buddha

The anthropomorphic form of the Buddha in Gandhara and Mathura developed simultaneously and yet resulted in remarkably distinct styles. [2] The Gandhara region’s encounter with Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C.E. and its history of Indo-Greek rulers in the centuries thereafter meant that a classical and Hellenistic (Greek) style of art and architecture was a part of the Gandhara region’s artistic vocabulary. Buddhas from Gandhara show a familiarity with Greco-Roman styles of sculpture; this is apparent in the comparison below, for example, in the drapery, hair, facial features, and musculature of the Gandhara Buddha.

Comparison of a Buddha from Gandhara with a Roman sculpture. Left: Buddha, c. 2nd–3rd century C.E., Gandhara, schist (Tokyo National Museum); right: “Caligula,” 1st century C.E., Roman, marble (Virginia Museum of Fine Art)

Mathura Buddha

As opposed to their Gandharan counterparts—with their inward-looking meditative expressions—Buddhas produced contemporaneously in Mathura look directly at us, as we see in the Seated Buddha. Their heads are smooth and topped with the kaparda (Sanskrit for a braided and coiled hairstyle) in striking contrast to the stylized hair of the Buddhas of Gandhara. They are also most often depicted wearing monastic robes (known as sangati) with one shoulder left bare.

Left: Yaksha figure, c. 150 B.C.E., approximately 8 feet high (Government Museum, Mathura, photo: Biswarup Ganguly, CC BY-3.0); right: Bala Bodhisattva, c. 130 C.E., approximately 6 feet 7 inches (Sarnath Museum, ©Archaeological Survey of India)

Artists in Mathura were inspired by the regional style of sculptures. Art historians have suggested that one inspiration for the Mathura style of the Buddha may be images of yakshas (male fertility spirits). A comparison of a standing yaksha image with a standing sculpture known as the Bala Bodhisattva reveals shared commonalities in their monumental size, columnar character, emphatically frontal attitude, and broad shoulders.

Artists would have refined existing sculptural forms (like that of the Yaksha figure) to create the newly popular anthropomorphic form of the Buddha. Although Bala Bodhisattva is identified not as the Buddha but rather as a bodhisattva (a being who is on the path to enlightenment) the iconographic treatment of the Buddha and bodhisattvas is identical in this early period.

Standing Buddha, c. 5th century C.E., Gupta period (©2017 The Presidents Secretariat, Rashtrapati Bhavan)

Images produced in Mathura in the Gupta period (c. 4th–7th centuries C.E.), like this Standing Buddha, would develop the Mathura style of the Kushan period even further. The Buddha’s facial features are softer, the folds on his robe (which will cover both of his shoulders) are a cascade of looped strings, his hair is beautifully coiled, and his eyes lower, looking inward.

Standing Buddha from the Gupta period and Seated Buddha with Two Attendants from the earlier Kushan period illustrate the development of the Buddha image in early history. Both images were produced in Mathura from the same stone and both represent a standard type of Buddha image from their respective eras. They are apt examples of how artistic processes and styles change over time.

Notes:

[1] In particular, a type of “Buddhist Sanskrit.” See Gérard Fussman cited under References.

[2] The question of which style of Buddha came first (i.e., the Buddha from Mathura or Gandhara) and hence represents the earliest type of anthropomorphic Buddha image has been a long debated issue. See Ananda K. Coomaraswamy and Alfred Foucher cited below.

Additional resources:

Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, “The Origin of the Buddha Image,” The Art Bulletin 9, no. 4 (1927): 287–329.

Vidya Dehejia, Indian Art (London: Phaidon Press, 1997).

Alfred Foucher, “The Greek Origin of the Image of Buddha.” In Alfred Foucher, The Beginnings of Buddhist Art and other Essays in Indian and Central–Asian Archaeology (Paris: Paul Geuthner, 1997), pp. 111–137.

Gérard Fussman, “Documents épigraphiques kochans (V). Buddha et Bodhisattva dans l’art de Mathura: deux Bodhisattvas inscrits de l’an 4 et l’an 8,” Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient (1988), pp. 5–26.

Prudence R. Myer, “Bodhisattvas and Buddhas: Early Buddhist Images from Mathura,” Artibus Asiae 47, no. 2 (1986): 107–142.

Sonya Rhie Quintanilla, History of Early Stone Sculpture At Mathura, ca. 150 BCE–100 C.E. (Leiden: Brill, 2007).

Ju-Hyung Rhi, “From Bodhisattva to Buddha: The Beginning of Iconic Representation in Buddhist Art,” Artibus Asiae 54, no. 3 / 4 (1994): 207–225.