Andrea del Verrocchio (with Leonardo), Baptism of Christ, 1470–75, oil and tempera on panel, 180 x 152 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence); Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

When you think of the Renaissance, the names that come to mind are probably the artists of this period (the High Renaissance): Leonardo and Michelangelo, for instance. And perhaps when you think of the greatest work of art in the western world, Michelangelo’s Sistine Ceiling might come to mind. This is a period of big, ambitious projects.

Fra Filippo Lippi, Madonna and Child with Two Angels, c. 1460–65, tempera on panel, 95 x 63.5 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

How is the High Renaissance different from the Early Renaissance?

As the Humanism of the Early Renaissance develops, a problem arises. Have a look at Fra Filippo Lippi’s Madonna and Child with Angels. We see a Madonna and Christ Child that have become so real—the figures appear so human—that in some ways we can hardly tell that these are divine figures (except perhaps for the faint outline of a halo, and Mary’s sorrowful expression and hands clasped in prayer). On the other hand, in the Middle Ages, the need to create transcendent spiritual figures, meant a move toward abstraction—toward flatness and elongation.

In the Early Renaissance then, a tension arises. To create spiritual figures, your image can’t look very real, and if you want your image to appear real, then you sacrifice some spirituality. In the late 15th century though, Leonardo da Vinci creates figures who are physical and real (just as real as Lippi’s or Masaccio’s figures), and yet they have an undeniable and intense spirituality. We could say that Leonardo unites the real and spiritual, or soul and substance.

Andrea del Verrocchio (with Leonardo), Baptism of Christ, 1470–75, oil and tempera on panel, 180 x 152 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The best way to see this is in this painting by Verrocchio—an important Early Renaissance artist who Leonardo was apprenticed to when he was young. Verrocchio asked Leonardo to paint one of the angels in his painting of the Baptism of Christ.

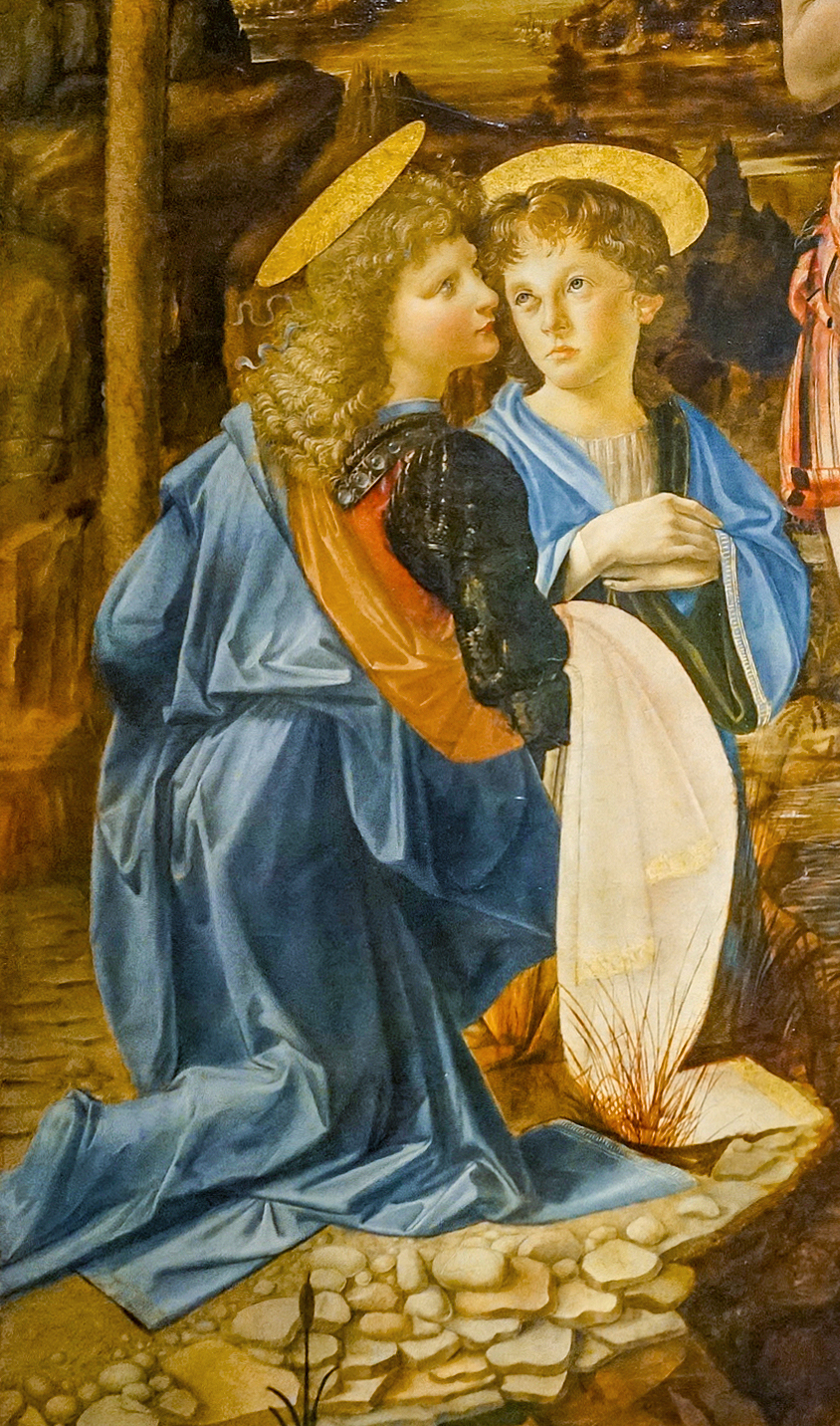

Detail, Andrea del Verrocchio (with Leonardo), Baptism of Christ, 1470–75, oil and tempera on panel, 180 x 152 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Can you tell which angel is Leonardo’s? One angel should look more like a boy—that’s the Early Renaissance angel (the one painted by Verrocchio) and the other angel should look truly divine, sent by God from heaven (that’s Leonardo’s angel).

The angel on the left is Leonardo’s.

Leonardo’s angel is ideally beautiful and moves in a graceful and complex way, twisting her upper body to the left but raising her head up and to the right. Figures that move elegantly and that are ideally beautiful are typical of the High Renaissance.

Additional resources

Expanding the Renaissance: a new Smarthistory initiative.

Read a chapter in our textbook, Reframing Art History, about rethinking how we approach Italian renaissance art (art in republics as well as in sovereign states).

Explore Leonardo from The National Gallery.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”HighRenaissance,”]