Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Self-Portrait with her Daughter, Julie, 1789, oil on canvas, 130 x 94 cm (Musée du Louvre). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Self-Portrait with Her Daughter Julie (à l’Antique), 1789, oil on wood, 130 x 94 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

During the course of her lifetime, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun painted many self-portraits, including her 1789 Self-Portrait with Her Daughter Julie (à l’Antique). In this intimate painting, she is seated on a bench as her daughter Julie leans into her body, and the arms of mother and daughter circle around each other. What differentiates this work from other self-portraits is her choice of attire. In this work, she appears to be wearing a one-shouldered dress that resembles the ancient Greek chiton, a garment not worn since antiquity. Why would the artist dress this way?

What is she wearing?

Élisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun, Self-Portrait, 1790, oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

While other self-portraits by Vigée Le Brun show her wearing fashionable but modest dress (see for example her self-portrait from 1790), this garment exposes one shoulder and the upper chest area of her body. Although Vigée Le Brun wrote in her memoirs that she often “wore white dresses in muslin or linen lawn,” [1] she is not wearing an actual dress in this self-portrait, but one that has been formed from a length of white cloth wrapped over one shoulder and around her body. The cloth is held in place with a red scarf that is bound twice around her torso and fastened underneath her bust. A length of green silk is draped across her legs and a red ribbon is tied around her unpowdered hair. The artist’s considerable skill in rendering cloth is evident but there is another message intended by her choice of dress in this work.

Why would she dress this way for her self-portrait?

As a woman artist in eighteenth century France, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun had to work harder to gain access to the profession than a man with comparable skills, especially since women were not permitted access to life drawing classes. At the time, the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture) governed the profession of art in France, such that only members of the Academy had the right to publicly exhibit their work in the official salons. Although Vigée Le Brun was initially denied membership to the Academy, in 1783 the king of France ordered an exception be made and the artist became one of four female members.

Raphael, The Small Cowper Madonna, c. 1505, oil on panel, 59.5 x 44 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC)

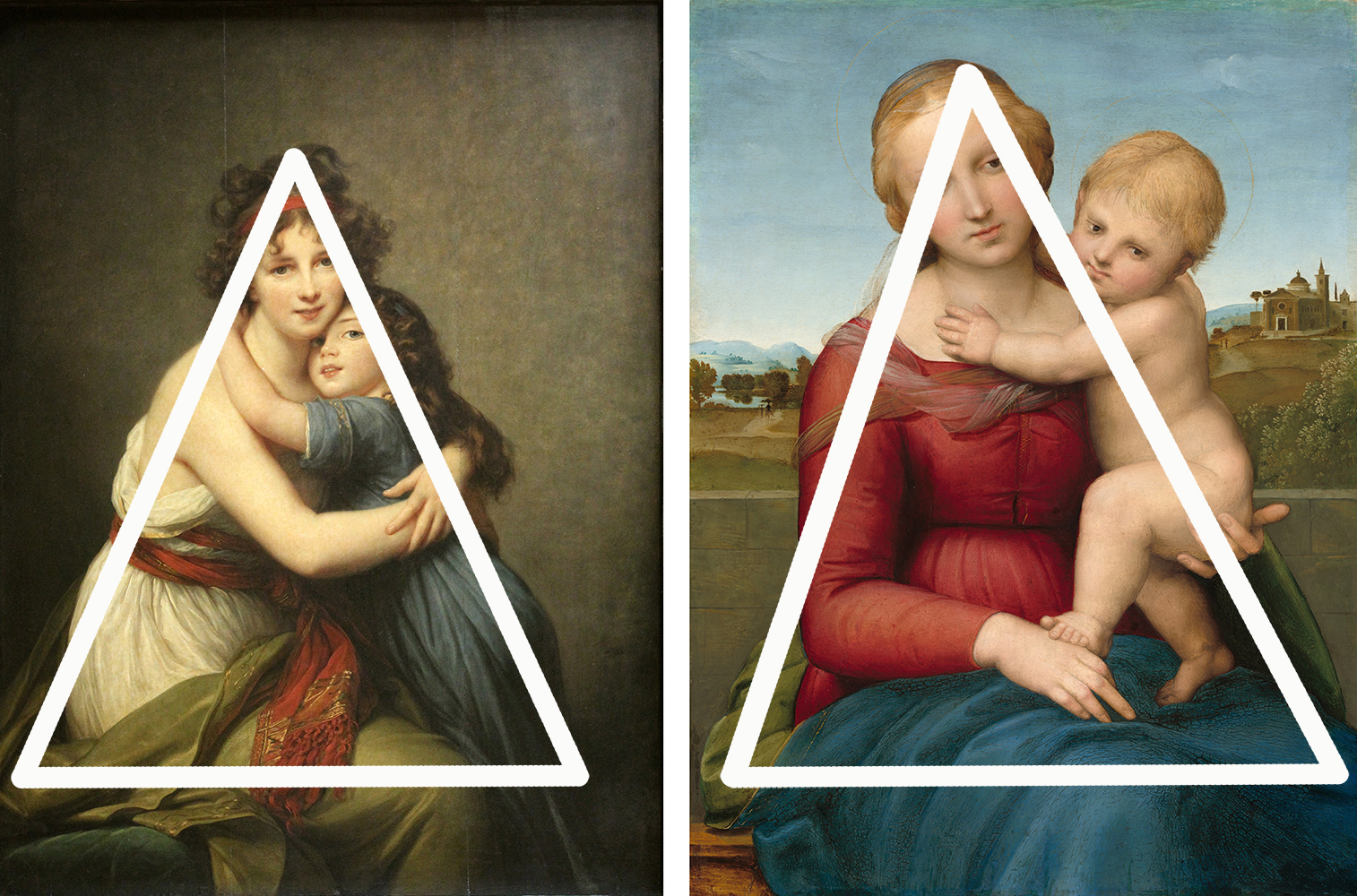

An artist’s self-portrait is a form of calling card that not only demonstrates skills in achieving a likeness but may also be designed to convey messages about the artist’s identity and inner life. Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun’s design of her 1789 self-portrait with her daughter echoes that of the Renaissance painter Raphael, a much-admired artist in eighteenth century France. Vigée Le Brun’s pose with her daughter creates a triangular composition that is reminiscent of Raphael’s Madonna and Child in The Small Cowper Madonna. In Raphael’s work, the arms of baby Jesus encircle his mother’s neck and the colours red, blue and green predominate. In addition, the manner in which the drapery falls across the lap in Le Brun’s work also seems to emulate Raphael.

Comparison of the compositions of Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun’s Self-Portrait with Her Daughter Julie (à l’Antique), left and Raphael’s Small Cowper Madonna, right

Aside from the reference to Raphael, the draped cloth worn by Vigée Le Brun also creates a timeless quality that harkens back to the classical period. Although a more informal and lightweight type of long-sleeved dress was worn in the 1780s by women including the artist and her clients, the dress worn by the artist in this particular self-portrait is quite different from the the chemise á la reine. The garment worn by Vigée Le Brun in this work bares one shoulder and, in this way, closely resembles a chiton, a sleeveless and form-fitting dress created from draped cloth. Many examples of the chiton can be seen ancient Greek sculpture, including a marble statue of Aphrodite from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Marble statue of Aphrodite, the so-called Venus Genetrix, 1st-2nd century C.E., marble , height 151.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

In creating a visual link to the classical era (ancient Greece and Rome) through her choice of dress, Elizabeth Vigée Le Brun may have wanted to reference legendary figures from that time. According to a Greek myth recounted by Pliny the Elder, the Corinthian maiden Dibutadis created the first drawing when she traced the shadow of her lover on a wall; this tale, in which the origin of drawing was linked to a desire to remember, was well known to artists in the eighteenth century. By wearing a form of dress linked to that time, Elizabeth Vigée Le Brun suggests that she is equally worthy of being remembered. Or she may have wanted the viewer to link her to the renowned painter Apelles of Kos from the fourth century B.C.E who Pliny the Elder considered superior to all other artists of the time. Either way, in dressing herself in a manner that is suggestive of classical antiquity, the artist invites viewers to equate her artwork to that of the artistic legends of the past.

Reading the clues of dress in a self-portrait

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Self-Portrait with Her Daughter Julie (à l’Antique), 1789, oil on wood, 130 x 94 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

When an artist creates a self-portrait, they can choose to wear whatever they feel best reflects their identity. In reading such works, it is important to consider the fact that the artist’s choice of attire may or may not reflect what was actually worn at the time but instead be a deliberate reference to another artist and/or another time period. Such is the case in Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun’s Self-Portrait with Her Daughter Julie (à l’Antique) in which she references the classical period in her manner of dress in order to cast herself as equal to legendary masters from the past.

Notes:

- Elisabeth Louise Vigée-Lebrun, Memoirs of Madame Vigée-Lebrun, Translated by Lionel Strachey, 1903. (London: Dodo Press, 2017), p. 42.

Additional resources:

Joseph Baillio, Katharine Baetjer, Paul Lang, Vigée Le Brun (New Haven: Yale University Press in association with The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2016).

Ingrid E. Mida, Reading Fashion in Art (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020).

Mary D. Sheriff, The Exceptional Woman: Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun and the Cultural Politics of Art (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1996).

Elisabeth Louise Vigée-Lebrun, Memoirs of Madame Vigée-Lebrun, Translated by Lionel Strachey, 1903. (London: Dodo Press, 2017).

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’re in the Louvre in Paris, looking at a self-portrait by the artist Vigée Le Brun.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:09] Interestingly, a portrait with her daughter, Julie. Being a mother who has a daughter named Julie, I especially love this painting.

Dr. Zucker: [0:18] When we think about late 18th century painting, we so often think of grand history painting or mythological subjects, and here we see a modest portrait that is all about intimacy.

Dr. Harris: [0:28] Vigée Le Brun was official court painter to the queen of France, to Marie Antoinette, and the year this was painted, 1789, is the year of the French Revolution. Only a couple of years from now, Marie Antoinette will be beheaded by the revolutionaries.

Dr. Zucker: [0:45] And Vigée Le Brun, herself, will leave France.

Dr. Harris: [0:48] She’ll have her citizenship revoked because of her support of the monarchy, and less than a decade later, her citizenship will be restored.

Dr. Zucker: [0:56] She was held in extremely high regard by the French painting establishment.

Dr. Harris: [1:00] It’s important to remember that there were only four positions available to women artists within the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, the institution in control of the fine arts in France. As a woman artist, she was up against many, many obstacles that her male colleagues didn’t face.

Dr. Zucker: [1:16] The brilliance of this painting makes clear why she was accepted into the Academy.

Dr. Harris: [1:20] That brilliance, to me, is in how much the faces and those gestures communicate the affection of a mother and daughter.

Dr. Zucker: [1:30] When this was painted, the monarchy was being accused of living a life that was entirely one of artifice.

Dr. Harris: [1:36] Out of touch with normal people in France.

Dr. Zucker: [1:39] And this is a painting that is all about authenticity. Vigée Le Brun herself moved among the aristocracy. In a sense, this painting is establishing that authenticity and aristocracy were not mutually exclusive.

[1:52] One of my favorite passages is the way that Julie’s right eye is nestled against the artist’s neck, shadowed by her chin. There is this wonderful sense of touch. Look at the way that the arms reach around. You can almost feel those small hands.

Dr. Harris: [2:05] To me, Vigée Le Brun’s eyes communicate sheer pleasure in this embrace of her daughter. Their bodies together form a pyramid. They form this single shape, as though they’re merged together as one.

[2:21] There’s a sense of genuine affection here, but I think you’re right, [that] was not something associated with the aristocracy. To assert that natural, genuine emotion as something that is felt by people who move in very high circles like Vigée Le Brun had a political dimension to it.

Dr. Zucker: [2:39] You can see that also in the dress. The artist is rendering herself in a dress that recalls the ancient Greek. This style, “à la grecque,” was part of this idea in the late 18th century that one can go back to a style that both ennobles but is in some ways more inherently natural.

Dr. Harris: [2:56] More simple, more direct.

Dr. Zucker: [2:57] In contrast to the ornate hoop skirts and gowns often worn during formal occasions.

Dr. Harris: [3:03] Look at Vigée Le Brun’s hair. The curls are unruly. There is an informality that did have this political dimension.

Dr. Zucker: [3:10] Although, I would say, it is a studied informality.

Dr. Harris: [3:13] Absolutely.

Dr. Zucker: [3:14] There’s something very contingent here. That embrace only lasts a moment.

Dr. Harris: [3:18] It only lasts for a moment, but the feeling of affection is universal and timeless. Vigée Le Brun was successful among the aristocracy in Europe, broadly. This was a woman who moved easily among the royal courts of Europe, and was highly successful.

Dr. Zucker: [3:35] In Russia, in Austria.

Dr. Harris: [3:37] In Italy.

Dr. Zucker: [3:38] And in London.

Dr. Harris: [3:39] Although there were many difficulties faced by women artists, it’s fascinating to see a woman as successful as Vigée Le Brun, presenting herself so powerfully as a mother.

[3:52] [music]