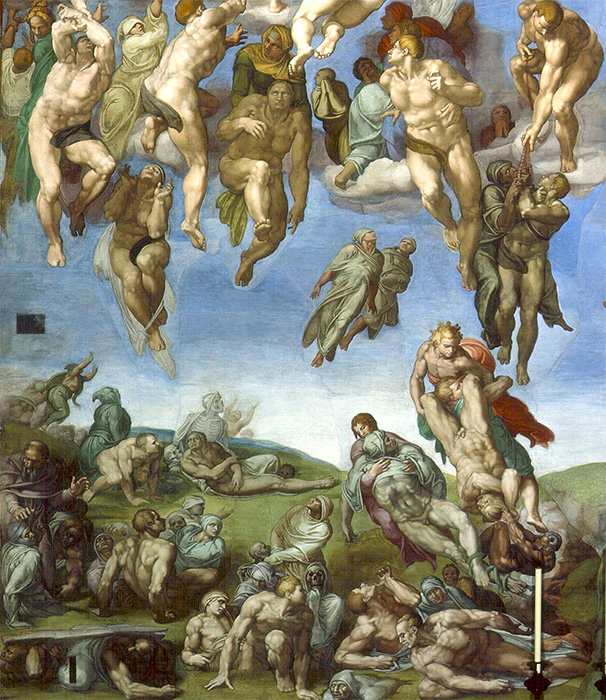

Michelangelo, Last Judgment, Sistine Chapel, fresco, 1534-1541 (Vatican City, Rome). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

“He will come to judge the living and the dead” (from the Apostle’s Creed, an early statement of Christian belief)

This is it. The moment all Christians await with both hope and dread. This is the end of time, the beginning of eternity when the mortal becomes immortal, when the elect join Christ in his heavenly kingdom and the damned are cast into the unending torments of hell. What a daunting task: to visualize the endgame of earthly existence – and furthermore, to do so in the Sistine Chapel, the private chapel of the papal court, where the leaders of the Church gathered to celebrate feast day liturgies, where the pope’s body was laid in state before his funeral, and where—to this day—the College of Cardinals meets to elect the next pope.

Historical & pictorial contexts

The decorative program of the Sistine Chapel encapsulates the history of salvation. It begins with God’s creation of the world and his covenant with the people of Israel (represented in the Old Testament scenes on the ceiling and south wall), and continues with the earthly life of Christ (on the north wall). The addition of the Last Judgment completed the narrative. The papal court, representatives of the earthly church, participated in this narrative; it filled the gap between Christ’s life and his Second Coming.

The composition

The elect (those going to heaven)

The damned (those going to hell)

In the company of Christ

While such details were meant to provoke terror in the viewer, Michelangelo’s painting is primarily about the triumph of Christ. The realm of heaven dominates. The elect encircle Christ; they loom large in the foreground and extend far into the depth of the painting, dissolving the boundary of the picture plane. Some hold the instruments of their martyrdom: Andrew the X-shaped cross, Lawrence the gridiron, St. Sebastian a bundle of arrows, to name only a few.

Especially prominent are St. John Baptist and St. Peter who flank Christ to the left and right and share his massive proportions (above). John, the last prophet, is identifiable by the camel pelt that covers his groin and dangles behind his legs; and, Peter, the first pope, is identified by the keys he returns to Christ. His role as the keeper of the keys to the kingdom of heaven has ended. This gesture was a vivid reminder to the pope that his reign as Christ’s vicar was temporary—in the end, he too will to answer to Christ.

In the lunettes (semi-circular spaces) at the top right and left, angels display the instruments of Christ’ Passion, thus connecting this triumphal moment to Christ’s sacrificial death. This portion of the wall projects one foot forward, making it visible to the priest at the altar below as he commemorates Christ’s sacrifice in the liturgy of the Eucharist.

Critical response: masterpiece or scandal?

Shortly after its unveiling in 1541, the Roman agent of Cardinal Gonzaga of Mantua reported: “The work is of such beauty that your excellency can imagine that there is no lack of those who condemn it. . . . [T]o my mind it is a work unlike any other to be seen anywhere.” Many praised the work as a masterpiece. They saw Michelangelo’s distinct figural style, with its complex poses, extreme foreshortening, and powerful (some might say excessive) musculature, as worthy of both the subject matter and the location. The sheer physicality of these muscular nudes affirmed the Catholic doctrine of bodily resurrection (that on the day of judgment, the dead would rise in their bodies, not as incorporeal souls).

A self-portrait

An epic painting

Like Dante in his great epic poem, The Divine Comedy, Michelangelo sought to create an epic painting, worthy of the grandeur of the moment. He used metaphor and allusion to ornament his subject. His educated audience would delight in his visual and literary references.

Additional resources:

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:03] More than 20 years after Michelangelo finished painting the frescoes on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, he was asked to do another fresco, this time on the altar wall.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:14] On the altar wall, Michelangelo painted “The Last Judgment.” This is an old subject in art history from the New Testament, from the Book of Revelation.

Dr. Zucker: [0:23] It’s not possible to overestimate how important this location is. This is the high altar of the Sistine Chapel. This is where the pope led mass. This is still the room where the College of Cardinals selects the next pope.

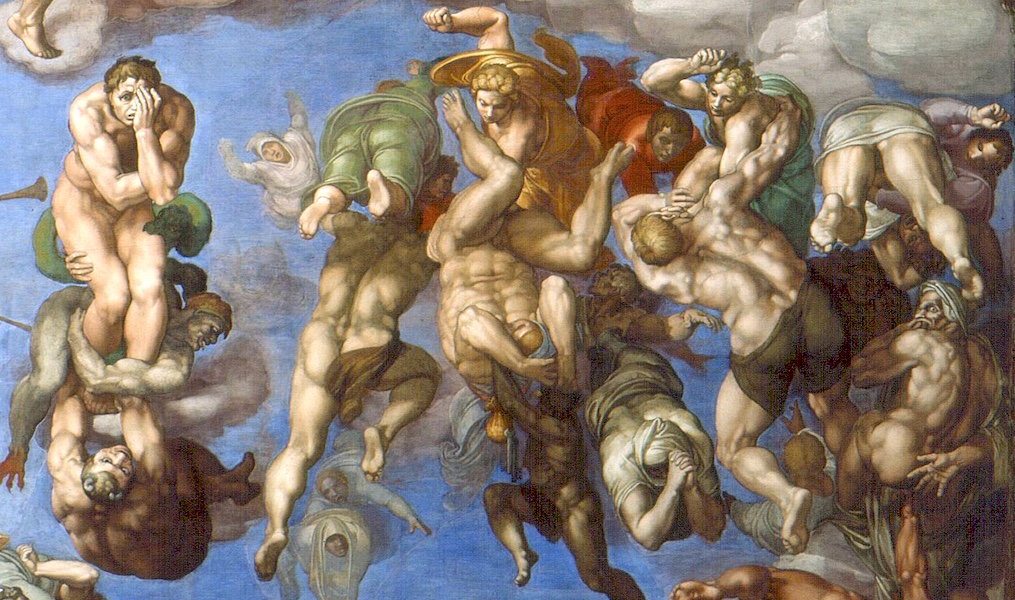

Dr. Harris: [0:35] Michelangelo paints Christ in the top center. On either side of Christ are saints and Old Testament figures, but below Christ we have the separation of the blessed from the damned: on Christ’s left, the damned who are going to hell, and on Christ’s right, the blessed who are going to heaven.

Dr. Zucker: [0:53] There is no more dramatic, no more powerful an image in the Catholic tradition. This is the end of time. We see Christ as a powerful judge who’s facing towards the damned, smiting them.

Dr. Harris: [1:06] He seems to be pointing to the wounds that he received on the cross. Beside him is the Virgin Mary, who crouches, powerless. She seems no longer to be able to intercede for mankind.

Dr. Zucker: [1:17] Although she looks down towards the blessed and seems to give over to Christ the damned.

Dr. Harris: [1:22] On Christ’s right, the blessed rise up to heaven from their graves. They’re pulled by angels who seem to assist them in their ascent to heaven.

Dr. Zucker: [1:32] I love these images because Michelangelo’s bodies are so dense. They’re so powerful. They’re so muscular. Even the spirits that are being resurrected, that they have to be lifted up with great effort. You can see one angel pulling up the blessed by a rosary.

Dr. Harris: [1:46] That’s right, a couple who’s literally being helped to ascend to heaven on the strength of their prayer, represented by the rosary beads. Directly below Christ, we see angels blowing their trumpets, awakening the dead from their graves.

Dr. Zucker: [1:59] Look at those long golden trumpets. This is in the Book of Revelation. It is made explicit here.

Dr. Harris: [2:04] But those angels don’t look very much like what we expect of angels. They are clearly male and powerful. Their heads are too small for their bodies. In blowing the trumpets, they look almost as though they’re going to explode with the power that that takes.

Dr. Zucker: [2:21] Well, they have to wake the dead, and that’s exactly what they’re doing. We can see crypts opening up. We can see graves. We can see these spirits that seem to emerge from the earth. It’s so unexpected, the physicality that Michelangelo has rendered the spirits [with].

[2:35] You would think that they would be incorporeal — they would have no mass, they would have no gravity, they would have no weight. But the opposite is true here. We feel the struggle, the difficulty of saving those souls, of bringing those souls into heaven.

Dr. Harris: [2:47] There’s no shying away from the body here. It is typical of Michelangelo that there’s this interest in the physicality of the body, the musculature of the body.

Dr. Zucker: [2:57] We see the emphasis on the body even more so perhaps on the right side, with the damned.

Dr. Harris: [3:02] Where on one side we see the blessed rising up toward heaven, on the opposite side we see the fires of hell and the damned being delivered there.

Dr. Zucker: [3:13] They’re being delivered on a boat. You can see the oarsman. This would be Charon, swinging his great oar to kick them off, and the demons are helping with their pitchforks and they’re actually harvesting the new souls for hell. It’s a pretty nasty scene.

Dr. Harris: [3:27] There are demons everywhere, pulling the figures off the boat and into hell.

Dr. Zucker: [3:31] It’s not just the demons that are doing their part. It’s also the angels. Just above this scene, we can see the damned who are being pushed down into hell. They seem to be striving desperately to get out, and they’re being punched by angels who are above them.

[3:45] Probably most arresting of all is the representation of a single figure. He’s got a devil that’s pulling at him from below, but it’s his psychological intensity that has given him the name the “Damned Man.”

Dr. Harris: [3:57] He seems to have just realized that he’s going to spend eternity in hell. There are demons also wrapped around his legs, pulling him down toward hell.

Dr. Zucker: [4:06] Look at his face. The hand is covering one eye as if he can’t believe, he can’t bear to see his fate. On the other hand, his other eye is open wide as if this is the moment of recognition.

Dr. Harris: [4:15] When we look at this scene here in the Sistine Chapel, we can look at Michelangelo’s early work on the ceiling right above us, where we see figures with bodies that are elegant and noble and have a sense of dignity.

[4:28] Here on the altar wall, in the scene of the Last Judgment, the figures look intentionally ugly, intentionally awkward. Their proportions are all wrong. Their heads are too small for their bodies. Their muscles look overdrawn.

Dr. Zucker: [4:42] That’s especially true of the representation of Christ. Look at the size of that torso. It’s completely out of scale, with his head and with his height. Michelangelo is looking at the human body not in the way that one might have in the High Renaissance, that is, as a reference back to the classical tradition and a kind of ideal proportion.

[5:01] Instead, he’s looking at the body as full of symbolic value. He’s willing to distort the body for the power of the painting itself.

Dr. Harris: [5:09] Right, the religious message is key here and the body is in the service of that message. In the intervening years, the Church has been challenged by Martin Luther and the beginnings of the Protestant Reformation.

Dr. Zucker: [5:23] This was a moment of great turmoil, and as Michelangelo gets older his earlier optimism seems to have been replaced by a deep pessimism.

Dr. Harris: [5:32] That might be best seen in the figure of Saint Catherine, who holds a wheel — which is her attribute, since she was martyred on a wheel — but here, she looks so ungainly. If we compare her to the beauty of Eve on the ceiling, the difference in the way Michelangelo is treating the body is clear.

Dr. Zucker: [5:48] Another figure that represents the profound pessimism of this fresco can be seen just to the right and below Christ. We see there a very large figure on a cloud, nude, who is looking up at Christ, holding a knife in one hand and a skin in the other. This is Saint Bartholomew, who was martyred by having his skin removed while he was alive.

Dr. Harris: [6:09] Saints are always identified by their attributes, often by the instrument of their martyrdom. Here, it makes sense that Bartholomew holds a knife.

Dr. Zucker: [6:18] But art historians noticed one curious decision by Michelangelo in the representation of Bartholomew. The face that we see in the skin is actually a self-portrait by the artist.

Dr. Harris: [6:29] So that means we must ask the question, why would Michelangelo put his own face, his own likeness, on the skin of Saint Bartholomew? Here in the middle between Christ, the savior, and the Damned Man?

Dr. Zucker: [6:44] Worse than that, Bartholomew seems to be holding the skin ever so lightly, as if his fingers might open and he might simply let it fall into the boat of Charon on its way to hell.

Dr. Harris: [6:54] This seems to express Michelangelo’s concern for the fate of his own soul, something that we also see in his poetry from this period.

[7:02] In fact, we can draw a diagonal line from the upper left, from the cross in the lunette, through the crown of thorns, through Christ, through the skin of Saint Bartholomew, the Damned Man, and then down to the fires of hell.

[7:17] [music]