Ibrahim El-Salahi, Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams, 1961-65, enamel and oil on cotton, 258.8 x 260 cm (Tate, London)

How would you paint a picture of something that’s not quite representable… like the sound of voices chanting, a spiritual vision, a childhood memory, or a dream that you can’t remember?

In his painting Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams, the Sudanese artist Ibrahim El-Salahi creates a masterful and haunting scene inspired by just these types of experiences.

Ibrahim El-Salahi, Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams, detail, enamel and oil on cotton, 258.8 x 260 cm (Tate, London)

A group of harrowing, evanescent figures approaches the viewer, some occupying the full height of the canvas. Their limbs are elongated and skeletal, and their mask-like faces are accented by hollow, circular eyes. Upturned crescent shapes sit atop their heads, reminiscent of bull’s horns or celestial symbols, giving them a sense of timeless power. Yet, the figures’ lower bodies seem to gradually fade into the background, transforming into abstract shapes like circles, lines, and hooks. Along the lower register, atmospheric mists of sandy and ashen tones disturb the limits of the figures’ outer contours—and all depicted forms seem to move fluidly between positive and negative space. Our eyes begin to deceive us: Are these creatures human, animal, or spirit?

This piece is typical of the artist’s work from the early-to-mid 1960s. El-Salahi uses an earthy color palette that invokes the region’s natural environment, and blends elements of modernist abstraction with a number of motifs drawn from the breadth of Sudanese cultural histories: the elegance of Arabic calligraphy, the attenuated forms of sub-Saharan figural sculpture, and aspects of ancient Nubian art. As such, it is also exemplary of the wider genre of postcolonial Modernism; created during the years in which many African countries gained independence from oppressive colonial regimes, it reflects a new articulation of African identity as being markedly global, and defiantly modern.

From Western realism to calligraphic abstraction

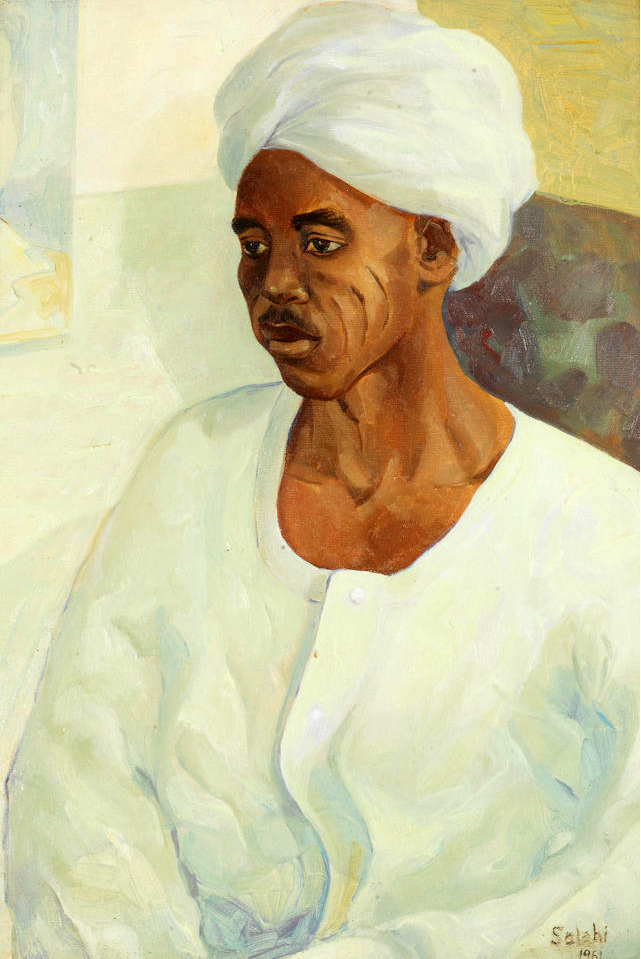

Born in 1930 in Omdurman, Sudan, El-Salahi’s initial artistic development was informed by his training under the British colonial system. He began his studies in 1949 as a painting major at Khartoum’s Gordon Memorial College, which offered a Western academic curriculum, before leaving his home country to attend the Slade School of Fine Art in London in the mid-1950s. There, he excelled in creating realistic portraits and landscape studies. It was during his time abroad that Sudan sought and gained its independence from the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, an alliance between Egypt and the British Empire that had asserted political control over the region since the late 19th century.

Ibrahim El-Salahi, Portrait of a Sudanese Gentleman, 1951, oil on board, 52.5 x 36cm (private collection)

When he returned to Sudan in 1957, El-Salahi suddenly found himself feeling disconnected from his home country. He realized that his Western training had alienated him from the concerns and visual expressions of the community he grew up in. As he later reflected:

[T]his radically changed attitude, the attitude of an extravagant, conceited young artist fresh from London, actually just hemmed me in. Over time, I came to see that conditions in Sudan required a very different approach on the part of the artist, who would otherwise be completely isolated from his audience. If I was to have a relationship with an audience, I had to examine the Sudanese environment, identify what it offered, assess its potential as an artistic resource and explore its possibilities as a complementary element in artistic creation. [1]

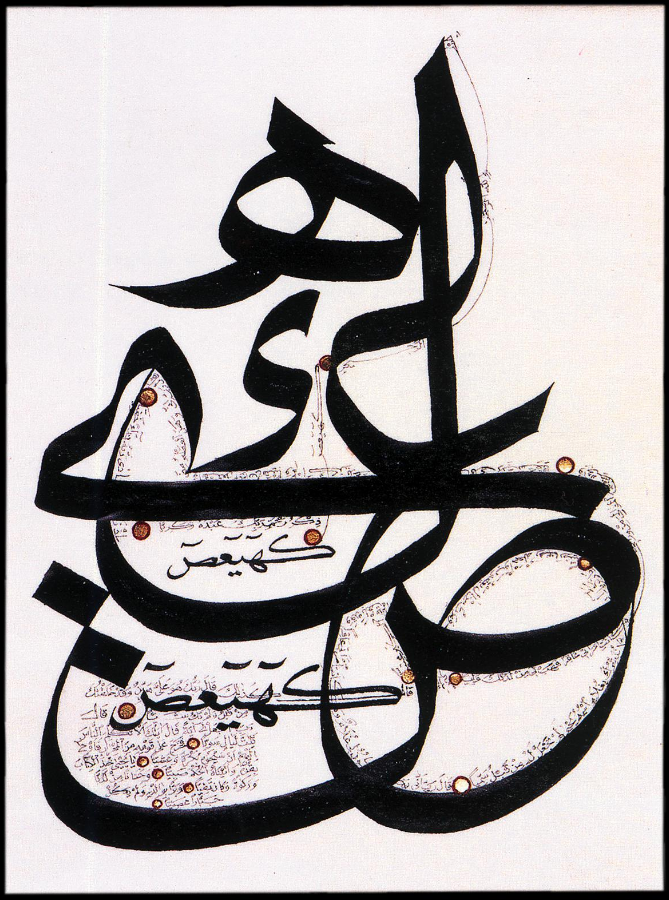

The artist began to experiment with a style of calligraphic abstraction that was, at the time, associated with the work of pioneering Sudanese artist Osman Waqialla. A leading figure in what would loosely become known as the Khartoum School, Waqialla was fascinated by the formal properties of calligraphic writing—its balancing of lights and darks, positive and negative space, and the lyrical motion of sweeping, interconnected strokes. He and his pupils worked to detatch the aesthetic components of calligraphic text from the sacred connotations it often carried, making reference instead to secular works of contemporary poetry.

Osman Waqialla, Kaf ha ya ayn sad, 1980, calligraphic text on paper, 17.5 x 13 cm (British Museum, London)

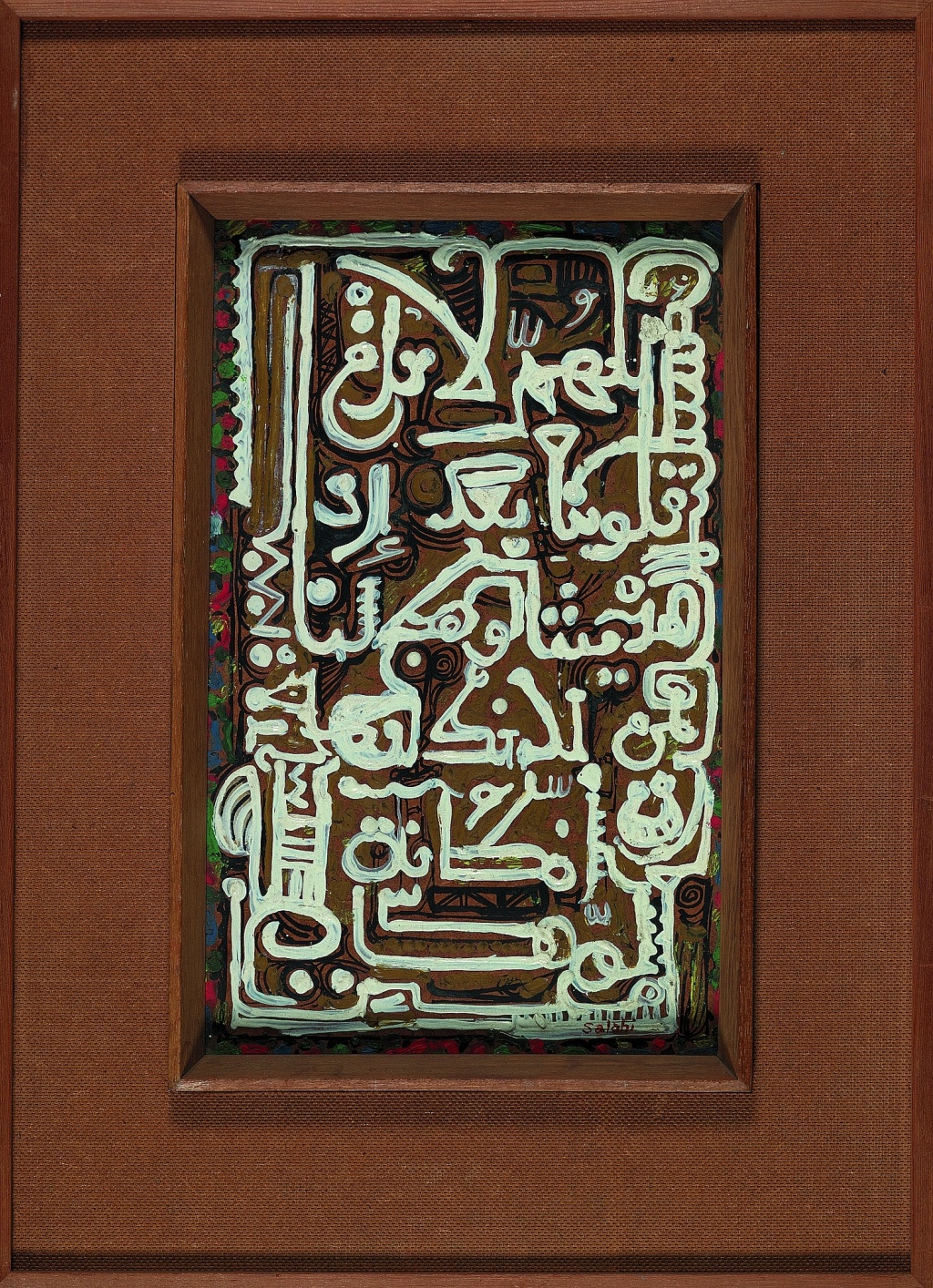

Similarly captivated by Arabic lettering, El-Salahi undertook a rigorous study of its visual elements. Eventually, he liberated the written text from its semiotic meaning: “I squeezed letters and decorative units into a narrow, limited space within the overall pictorial field. The letter became legible, yet abstract,” he reflected. “Later I considered separating the calligraphic symbol from its verbal representation, so that what was read referred only to the letter form and nothing else.” [2] In a number of early works, El-Salahi inventively transformed written marks into entangled webs of lines and curves.

Ibrahim El Salahi, The Prayer, 1960, oil on masonite, 61.3 × 44.5 cm (Iwalewahaus, Universität Bayreuth)

Adopting a subdued and somber color palette that is representative of the desert landscape of northern Sudan, the artist would gradually expand his experimentation to include art forms beyond Arabic calligraphy. The lines and hooks, associated with kufic writing, soon morphed into other forms: ghostly figures, animals, and vegetal motifs came to populate his compositions, as well as concentric linear patterns that the artist associated with sonic waves. In one of his most abstract canvases from this period, The Last Sound (1964) he represents the Islamic prayers for the dying, which accompany the soul’s passage between life and death.

Postcolonial modernism

El-Salahi’s work should be situated within the broader history of postcolonial Modernism in Africa. Throughout the 1960s, creative practitioners from across the continent and its diasporas produced radical innovations in art, literature, music and theatre. They wanted their art to reflect the cultural and political transformations that were sweeping the continent as it was liberated from colonial rule. Many looked to fuse modernist Western styles (to which they had been exposed through school or travel) with pre-colonial African visual forms. This essay on Uche Okeke, for instance, chronicles the influence of Igbo aesthetics on Nigerian art of the same period.

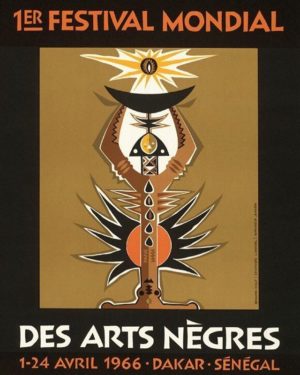

In the early 1960s, El-Salahi took part in a transnational workshop called the Mbari Artists and Writers Club. Located in Ibadan, Nigeria, it was run by the German expatriate Ulli Beier, and brought together artists and writers like Uche Okeke, Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Jacob Lawrence, and many others. El-Salahi also participated in landmark events of the Pan-Africanist movement, such as the 1966 First World Festival of Black Arts (Premier festival Mondial des arts nègres) in Dakar, Senegal, where artists, dancers and musicians from across the African diaspora gathered to express pride in Black artistic and cultural expression.

“The Jungle and The Desert”

In his unique interpretation of postcolonial Modernism, El-Salahi tapped into the diverse cultural history of Sudan and its surrounding regions. His home country saw the birth of the ancient Nubian civilization, later encountered by the Egyptian, Ptolemaic Greek and Roman Empires. It was also a crucial juncture in the early history of Christianity and the expansion of Islam.

When El-Salahi was growing up, the national borders of Sudan encompassed both the North (which is predominantly Islamic and culturally Arab) as well as the sub-Saharan South (largely inhabited by the Dinka and Nuer peoples). El-Salahi’s interest in this diverse artistic legacy is mirrored by the parallel evolution of a literary and poetic movement, The Jungle and Desert School (Madrasat al-Ghaba wa al-Sahra), whose writers also drew inspiration from both African and Arab sources. Unfortunately, long-standing religious and economic rifts between each of these contingencies have led to a series of violent civil wars across the region in recent decades, and the nation has since been divided following the secession of South Sudan in 2011.

El-Salahi’s style is, ultimately, expressive of his uniquely personal vision. Spiritual visions, childhood dreams, and sonic memories infuse his work with a haunting, elegiac quality that masterfully interweaves cross-cultural sources and personal experiences. As the artist stated,

[T]he work of art is but a springboard for the individual intellect, or is like a reflecting mirror bring us back to our own selves. The picture floats freely within the realm of a simple relationship between viewer and form, an invitation to visual meditation and to a better knowledge of the self. [3]

Notes:

- Ibrahim El-Salahi, “The Artist in His Own Words,” in Ibrahim El-Salahi: A Visionary Modernist, ed. Salah Hassan, Museum for African Art, New York (2012): p. 84.

- Ibid., p. 88.

- Ibid., p. 91.

Additional resources: