Sculpture of a woman removing a thorn from her foot, northwest side exterior wall, Lakshmana temple, Khajuraho, Chhatarpur District, Madhya Pradesh, India, dedicated 954 C.E. (image source)

Ideal female beauty

Look closely at the image to the left. Imagine an elegant woman walks barefoot along a path accompanied by her attendant. She steps on a thorn and turns—adeptly bending her left leg, twisting her body, and arching her back—to point out the thorn and ask her attendant’s help in removing it. As she turns the viewer sees her face: it is round like the full moon with a slender nose, plump lips, arched eyebrows, and eyes shaped like lotus petals. While her right hand points to the thorn in her foot, her left hand raises in a gesture of reassurance.

Images of beautiful women like this one from the northwest exterior wall of the Lakshmana Temple at Khajuraho in India have captivated viewers for centuries. Depicting idealized female beauty was important for temple architecture and considered auspicious, even protective. Texts written for temple builders describe different “types” of women to include within a temple’s sculptural program, and emphasize their roles as symbols of fertility, growth, and prosperity. Additionally, images of loving couples known as mithuna (literally “the state of being a couple”) appear on the Lakshmana temple as symbols of divine union and moksha, the final release from samsara (the cycle of death and rebirth).[1]

The temples at Khajuraho, including the Lakshmana temple, have become famous for these amorous images—variations of which graphically depict figures engaged in sexual intercourse. These erotic images were not intended to be titillating or provocative, but instead served ritual and symbolic function significant to the builders, patrons, and devotees of these captivating structures.[2]

Lakshmana temple, Khajuraho, Chhatarpur District, Madhya Pradesh, India, dedicated 954 C.E. (Chandella period), sandstone (photo: Christopher Voitus, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Chandella rule at Khajuraho

Location of Khajuraho, India

The Lakshmana temple was the first of several temples built by the Chandella kings in their newly-created capital of Khajuraho. Between the 10th and 13th centuries, the Chandellas patronized artists, poets, and performers, and built irrigation systems, palaces, and numerous temples out of sandstone. At one time over 80 temples existed at this site, including several Hindu temples dedicated to the gods Shiva, Vishnu, and Surya.[3] There were also temples built to honor the divine teachers of Jainism (an ancient Indian religion). Approximately 30 temples remain at Khajuraho today.

The original patron of the Lakshmana temple was a leader of the Chandella clan, Yashovarman, who gained control over territories in the Bundelkhand region of central India that was once part of the larger Pratihara Dynasty. Yashovarman sought to build a temple to legitimize his rule over these territories, though he died before it was finished. His son Dhanga completed the work and dedicated the temple in 954 C.E.

Nagara style architecture

Vaikuntha Vishnu, womb chamber (garba griha), Lakshmana temple. 1076-1099 C.E., sandstone (photo: Christine Chauvin, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

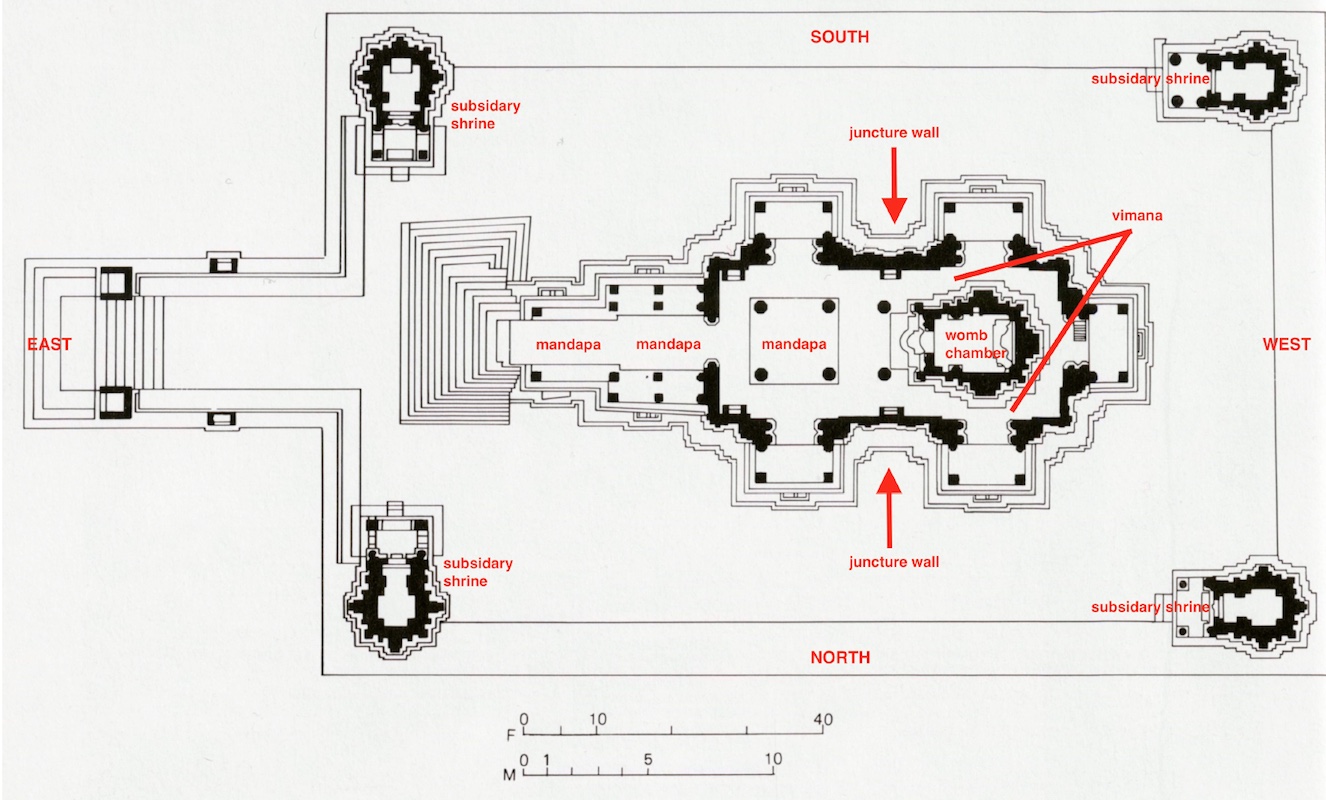

The central deity at the Lakshmana temple is an image of Vishnu in his three-headed form known as Vaikuntha[4] who sits inside the temple’s inner womb chamber also known as garba griha (above)—an architectural feature at the heart of all Hindu temples regardless of size or location. The womb chamber is the symbolic and physical core of the temple’s shrine. It is dark, windowless, and designed for intimate, individualized worship of the divine—quite different from large congregational worshipping spaces that characterize many Christian churches and Muslim mosques.

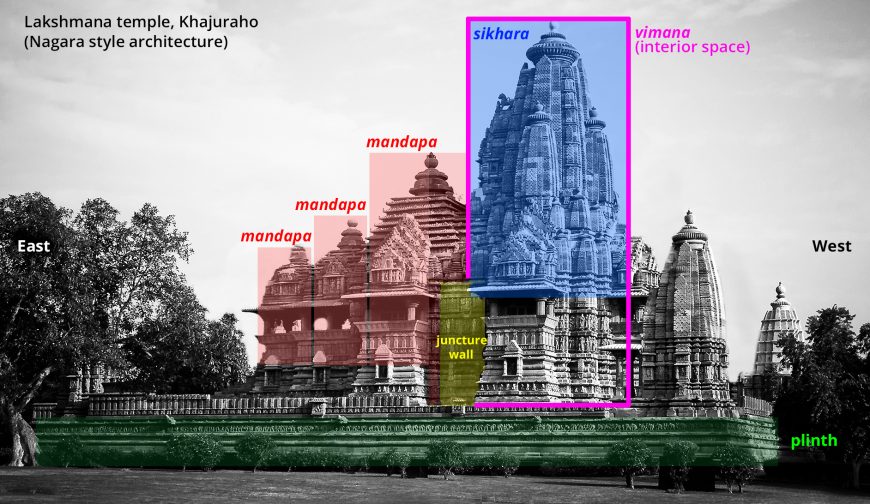

The Lakshmana Temple is an excellent example of Nagara style Hindu temple architecture.[5] In its most basic form, a Nagara temple consists of a shrine known as vimana (essentially the shell of the womb chamber) and a flat-roofed entry porch known as mandapa. The shrine of Nagara temples include a base platform and a large superstructure known as sikhara (meaning mountain peak), which viewers can see from a distance.[6] The Lakshmana temple’s superstructure appear like the many rising peaks of a mountain range.

Plan of Lakshmana temple

Approaching the divine

Devotees approach the Lakshamana temple from the east and walk around its entirety—an activity known as circumambulation. They begin walking along the large plinth of the temple’s base, moving in a clockwise direction starting from the left of the stairs. Sculpted friezes along the plinth depict images of daily life, love, and war and many recall historical events of the Chandella period (see image below and Google Street View).

Section of a narrative frieze encircling the temple at the level of the plinth, Lakshmana temple, Khajuraho, Chhatarpur District, Madhya Pradesh, India, dedicated 954 (photo: Sheep”R”Us, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Ganesha in niche, exterior mandapa wall, south side, Lakshmana temple, Khajuraho, Chhatarpur District, Madhya Pradesh, India, dedicated 954 (photo: Manuel Menal , CC BY-SA 2.0)

Devotees then climb the stairs of the plinth, and encounter another set of images, including deities sculpted within niches on the exterior wall of the temple ( view in Google Street View ).

In one niche (left) the elephant-headed Ganesha appears. His presence suggests that devotees are moving in the correct direction for circumambulation, as Ganesha is a god typically worshiped at the start of things.

Other sculpted forms appear nearby in lively, active postures: swaying hips, bent arms, and tilted heads which create a dramatic “triple-bend” opposite pose, all carved in deep relief emphasizing their three-dimensionality. It is here —specifically on the exterior juncture wall between the vimana and the mandapa (see diagram above) —where devotees encounter erotic images of couples embraced in sexual union (see image below and here on Google Street View ). This place of architectural juncture serves a symbolic function as the joining of the vimana and mandapa , accentuated by the depiction of “joined” couples.

Four smaller, subsidiary shrines sit at each corner of the plinth. These shrines appear like miniature temples with their own vimanas , sikharas, mandapas , and womb chambers with images of deities, originally other forms or avatars of Vishnu.

Following circumambulation of the exterior of the temple, devotees encounter three mandapas , which prepare them for entering the vimana . Each mandapa has a pyramidal-shaped roof that increases in size as devotees move from east to west.

Figural groupings on the outer temple including Shiva, Mithuna, and erotic couples, Lakshmana temple, Khajuraho, Chhatarpur District, Madhya Pradesh, India, dedicated 954 (photo: Antoine Taveneaux , CC BY-SA 3.0). View this on Goole Street View .

Once devotees pass through the third and final mandapa they find an enclosed passage along the wall of the shrine, allowing them to circumambulate this sacred structure in a clockwise direction. The act of circumambulation, of moving around the various components of the temple, allow devotees to physically experience this sacred space and with it the body of the divine.

Entrance to the Mandapa , Lakshmana Temple, Khajuraho, Chhatarpur District, Madhya Pradesh, India, dedicated 954 (photo: Antoine Taveneaux , CC BY-SA 3.0)

Notes:

[1] Mithuna figures appear on numerous Hindu temples and Buddhist monastic sites throughout South Asia from as early as the 1st century CE Maithuna is a related term that references figures depicted in the act of sexual intercourse.

[2] Some scholars suggest that these erotic images may be connected to Kapalika tantric practices prevalent at Khajuraho during Chandella rule. These practices included drinking wine, eating flesh, human sacrifice, using human skulls as drinking vessels, and sexual union, particularly with females who were given central importance (as the seat of the divine). The idea was that by indulging in the bodily and material world, a practitioner was able to overcome the temptations of the senses. However, these esoteric practices were generally looked down upon by others in South Asian society and accordingly very often were done in secrecy, which raises questions about the logic of including Kapalika-related images on the exterior of a temple for all to see.

[3] There is also at least one temple at Khajuraho, the Chausath Yogini Temple, dedicated to the Hindu Goddess Durga and 64 (“chausath”) of her female attendants known as yoginis. It was built by a previous dynasty who ruled in the area before the Chandella kings rose to power.

[4] The original Vaikuntha at Lakshmana temple was itself politically significant: Yashovarman took it from the Pratihara overlord of the region. Susan Huntington indicates that the stone image currently on view at Lakshmana temple, while indeed a form of Vaikuntha, is not in fact the original (metal) image which Yashovarman appropriated from the Pratihara ruler. Appropriating another ruler’s family deity as a political maneuver was a widespread practice throughout South Asia. For more on this practice, see the work of Finbarr B. Flood, Objects of Translation: Material Culture and Medieval ‘Hindu-Muslim’ Encounter(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), particularly Chapter 4. A similar Vaikuntha image now appears in the central shrine of the Lakshmana temple and is notable for its depiction of the deity’s three heads with a human face at the front (east), a lion’s face on the left (south), and a boar’s face on the right (north) —the latter two of which are now badly damaged. An implied, though not visible fourth face is that of a demon’s head at the rear of the image (west-facing) which has led some scholars to identify this form as Chaturmurti or four-faced.

[5] In general, there are two main styles of Hindu temple architecture: the Nagara style, which dominates temples from the northern regions of India, and the Dravida style, which appears more often in the South.

[6] The base platform is sometimes known as pitha , meaning “seat.” A flattened bulb-shaped topper known as amalaka appears at the top of the superstructure or sikhara . The amalaka is named after the local amla fruit and is symbolic of abundance and growth.

Additional resources:

Beliefs Made Visible: Hindu Temples in South Asia

Hinduism and Buddhism, an Introduction

Ganesha in a Temple Niche from the Asian Art Museum

Hindu Temples from the Asian Art Museum

Vidya Dehejia, “Reading Love Imagery on the Indian Temple,” Love in Asian Art and Culture (Washington, DC: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution), pp. 97-112.

Vidya Dehejia, The Body Adorned: Dissolving Boundaries Between Sacred and Profane in India’s Art (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009).

Tapati Guha-Thakurta, “Art History and the Nude: On Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality in Contemporary India,” in Monuments, Objects, Histories: Institutions of Art in Colonial and Postcolonial India (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004).

Susan L. Huntington, The Art of Ancient India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain (New York: Weatherhill, 1985), 466-477.

Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple , vols. 1 and 2 (Calcutta: University of Calcutta, 1946), pp. 131-144 and 346-347.

Michael Meister, “Juncture and Conjuncture: Punning and Temple Architecture,” Artibus Asiae , Vol. 41, No. 2/3 (1979), pp. 226-234.