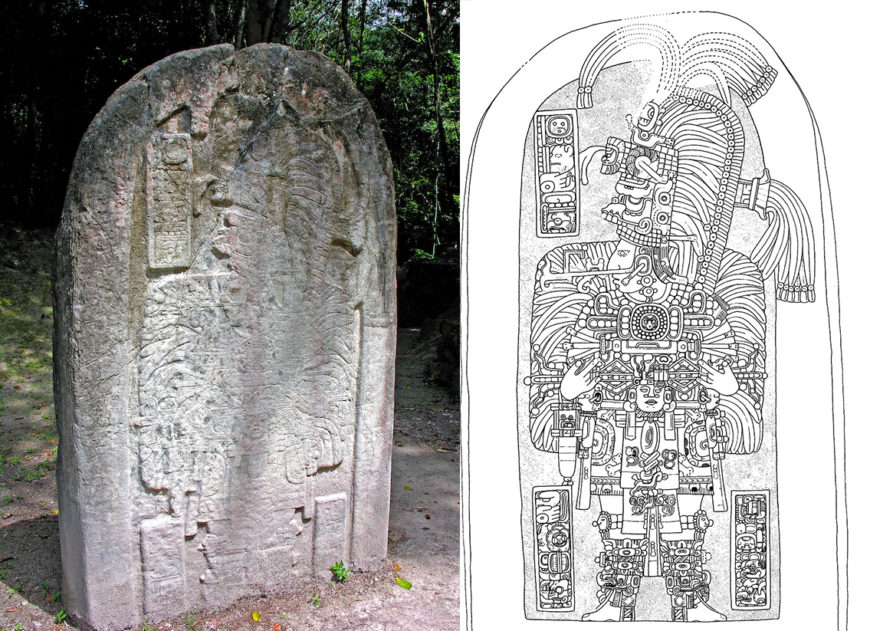

Stela 16, c. 711 C.E. (Classic Period), Tikal, Guatemala, 3.5 x 1.28 m (photo: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Have you ever used an Instagram filter to make someone or something appear more perfect? When we post on social media, we can use filters to digitally manipulate images, removing some features and emphasizing others. The idea of creating a flawless image of yourself is not a new one. From Augustus of Primaporta to contemporary presidential portraits, rulers throughout history have commissioned works that depict them as they want to be seen. The Maya of Mesoamerica were no exception: Tikal Stela 16 is an example of a royal portrait stela, and it depicts Jasaw Chan K’awiil, a ruler of Tikal, an important Maya city in what is today Guatemala. Maya artists carved this stela during the Classic period (c. 300–900 C.E.). This extravagant representation of the king reveals layers of meaning about his wealth and power—and the rituals he completed as ruler related to time and the maintenance of world order.

Map showing the extent of the Maya civilization (red), compared to other Mesoamerica cultures (black). Today, these sites are located in the countries of Mexico, Belize, Honduras and Guatemala (image: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Maya were never a unified empire. Instead, during this era of Maya history, a number of important polities struggled for power, and rulers throughout the Maya area commissioned sculptures that used figural imagery and hieroglyphic writing to proclaim their importance and record specific actions.

Left: Stela 16, c. 711 C.E., Classic Period, from the site of Tikal, Guatemala, 3.5 x 1.28 m (photo: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0); right: line drawing of Stela 16. This sculpture was recovered by archaeologists in an architectural complex just to the west of the city center.

The royal body

The image of the king is carved in low relief. Although the detailed carving is difficult to see today (in this case, largely due to weathering), it once would have been brightly painted, which would have helped viewers “read” the image. As we can see on the stela and the line drawing of it (created by archaeologists to help us see the images more clearly), the king stands in the center of the composition, wearing formal dress. The body of Jasaw Chan K’awiil is frontal, but his face is turned to the right so that his features are in profile. This was a standard method for the depiction of Classic Maya rulers.

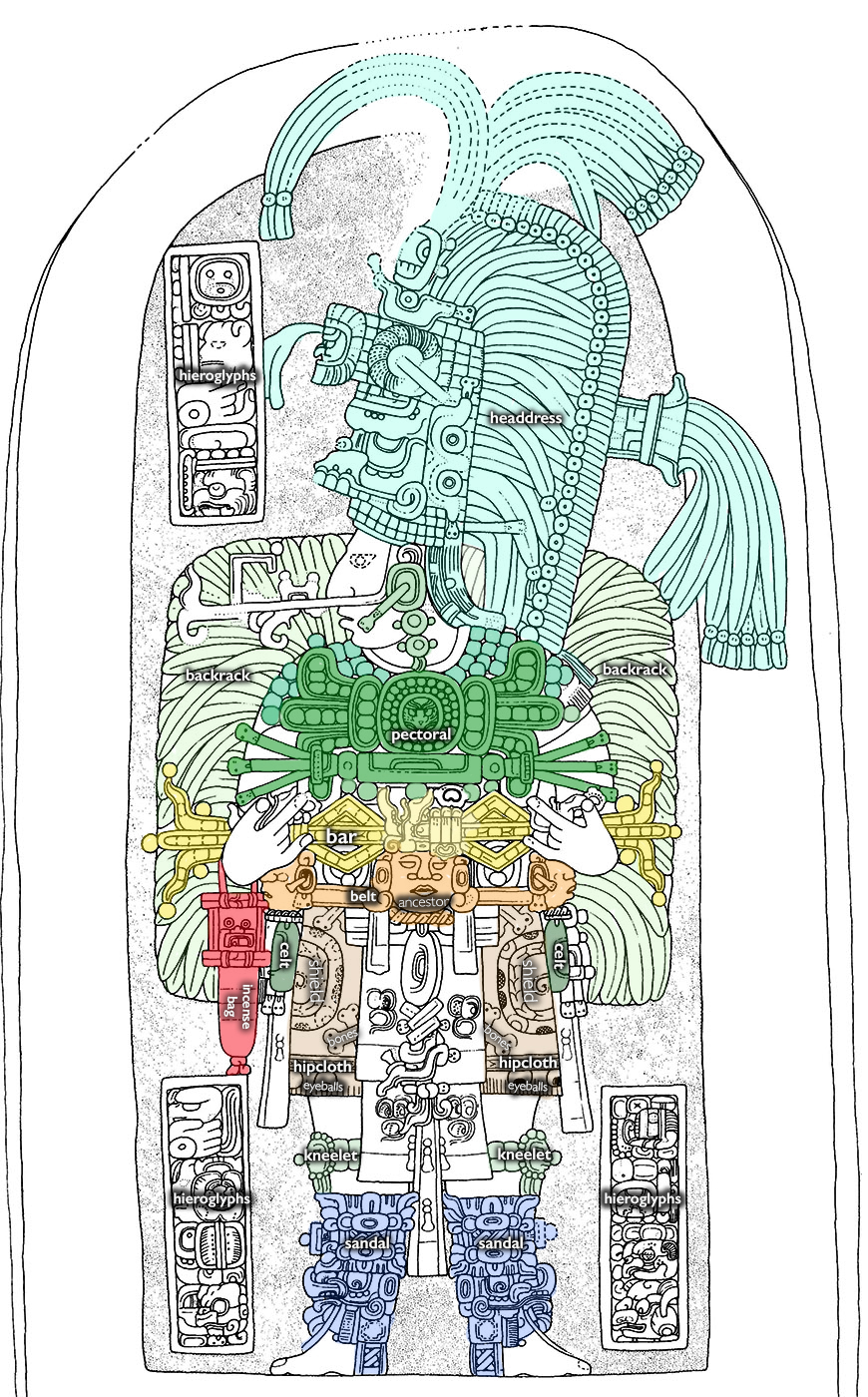

Annotated image of Stela 16, Tikal. The colors used in this image are not the actual colors that were once painted on the stela, but are used here to help readers see the stela.

The depiction of Jasaw Chan K’awiil emphasizes his wealth, power, and performance. He is bedecked with rich clothing and jewelry, made of materials likely traded over long distances and worked by specialized artisans. He wears an enormous amount of jade, the most valuable material in the Classic Maya world. The blue-green color of jade recalled the green of growing maize and the blue of rushing water, and it emphasized fertility and growth. In the image on the stela, the king wears large jade earspools, which are large round ear ornaments. The king’s pectoral, or chest ornament, is made up of round jade beads.

From his hip belt dangle celts, oval-shaped jade ornaments that would have rung like bells when they came into contact with one another. The head at the center of his belt is also made of jade, and most likely represents an ancestor. Maya kings often wore representations of their ancestors on their belts to emphasize the legitimacy of their rule. Jade kneelets (like bracelets, but worn around the knee) complement the other jade jewelry, as do the king’s elaborate sandals.

Another indication of wealth are the quetzal feathers that ornament the king’s royal regalia. The quetzal—today the national bird of Guatemala—is a reclusive bird that lives in cloud forests. Each male bird grows two long green tail feathers, and these feathers were key parts of ceremonial dress for Maya elites. Jasaw Chan Kawiil’s headdress is covered in quetzal feathers, which splay to the top and side.

Detail of the headdress and feathered backrack in the upper portion of Stela 16, c. 711 C.E., Classic Period, from the site of Tikal, Guatemala, 3.5 x 1.28 m (photo: Luis Alveart, CC BY-NC 2.0)

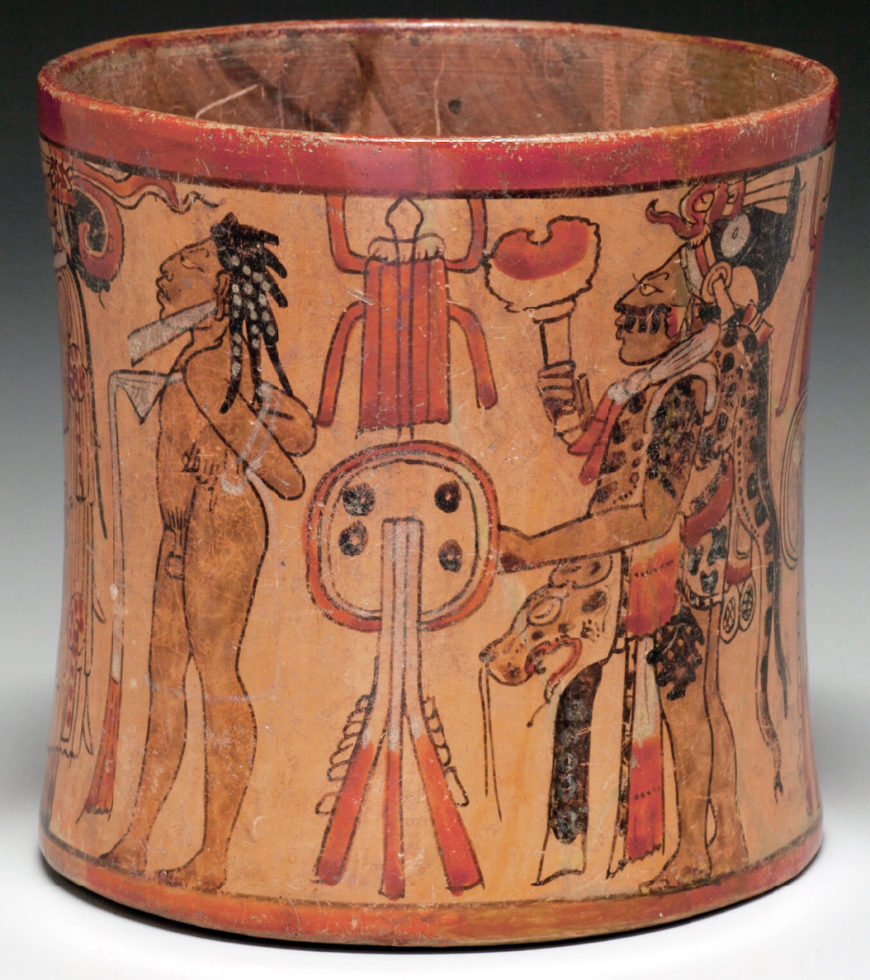

Maya Vessel with a Procession of Warriors, c. 750–850 C.E., Late Classic Period, polychromed ceramic, 16 cm diameter (Kimbell Art Museum)

He also wears a “backrack,” likely a wooden or papier mache frame worn on the back and covered with feathers. We can see these feathers emerging all around his torso.

The jade and quetzal feathers emphasize the wealth and symbolic power of the king—but other elements point to military power as well. His hipcloth, in particular, is covered with references to warfare. The large, round objects that decorate the skirt are shields, like those carried into battle by Classic Maya warriors. Surrounding the shields are crossed bones, and the fringe at the bottom of the skirt is decorated with eyeballs. These most likely represent trophies, body parts taken from conquered enemies during battle. The skirt reminds viewers that the ruler wielded military as well as religious power.

Single rows of hieroglyphs hover in three corners of the sculpture, and they describe what’s going on. At the upper left, the first two glyphs record the date, which corresponds to 711 C.E. The next glyphs describe what the king is doing: participating in a ritual related to the passage of time.

Detail of the lower portion, with glyphs to the right and left of the ruler’s legs, Stela 16, c. 711 C.E., Classic Period, from the site of Tikal, Guatemala, 3.5 x 1.28 m (photo: Luis Alveart, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Accomplished astronomers, the Maya maintained multiple calendar systems and kept detailed records of when specific events happened. The inscription goes on to include more calendrical information as well as the name and title of the king, identifying him as the holy lord of Tikal. The inscription ends by referring to Jasaw Chan K’awiil as a “three k’atun lord.” “A k’atun is a period of twenty years, and this indicates that Jasaw Chan K‘awiil was between 39 and 59 years old when this event took place.

Rituals related to time

What is Jasaw Chan K’awiil doing here? The hieroglyphic inscription indicates that the stela commemorates a ritual performed by the king. The image supports this statement, showing us what the ritual may have looked like when performed live. In his hands, the king holds an object that scholars call “the ceremonial bar.” It is unclear what the bar is made of, or what exactly it meant to viewers, but rulers on stelae throughout the southern Maya lowlands carry the bar in various scenes. The bag that dangles from his right wrist is an incense bag. This indicates that the rite Jasaw Chan K’awiil participated in probably involved the burning of incense. Scattering incense into braziers was considered a way to communicate with otherworldly forces.

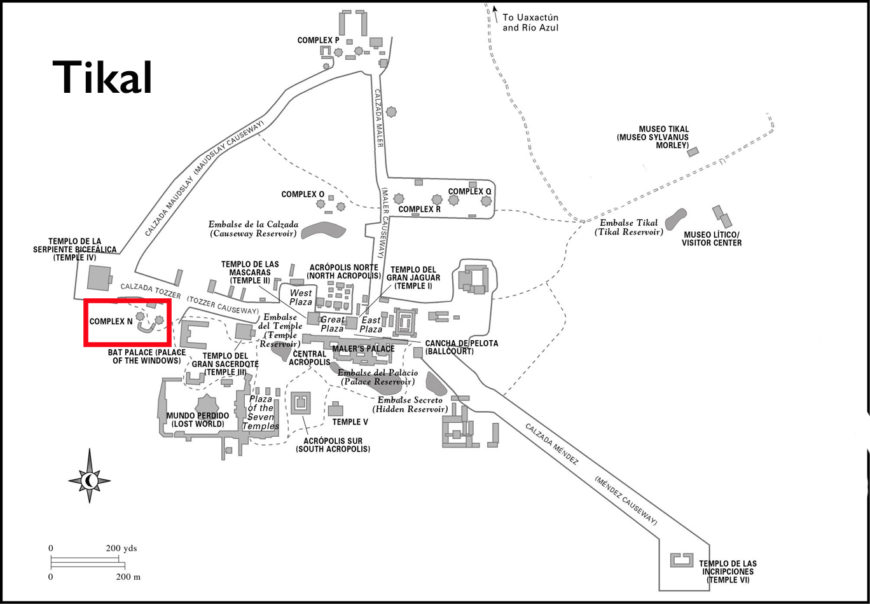

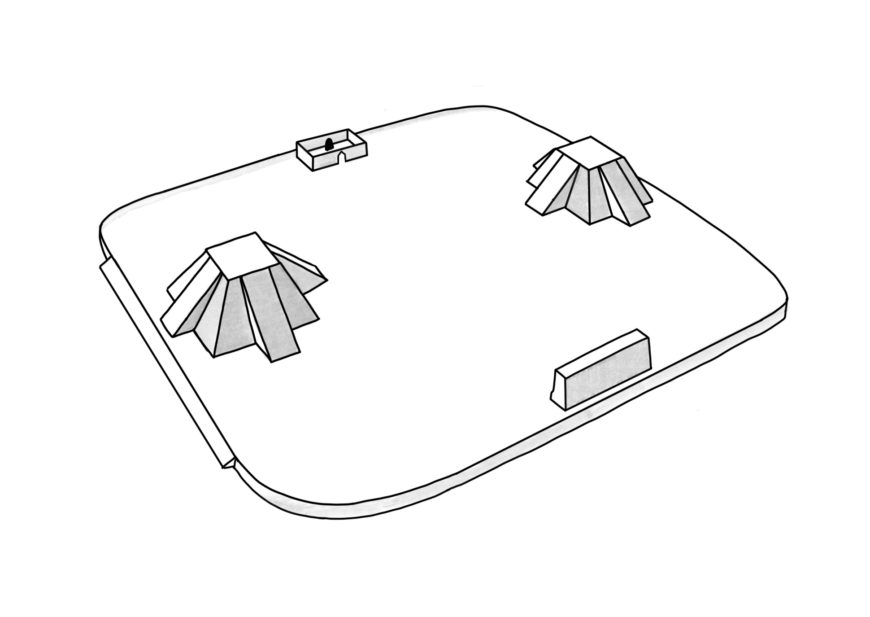

The ritual commemorated on this stela celebrated the completion of a k’atun (again, a twenty-year period). For the ancient Maya, the orderly passage of time was not a given. Instead, kings were responsible for completing rituals to ensure that time would continue as expected, and the completion of major periods of time was commemorated in artwork. At Tikal, kings commissioned special architectural complexes to mark the end of a k’atun that we now call twin pyramid complexes. They included two buildings and a walled enclosure arranged around a large patio. Inside the enclosure was a stela, placed vertically in the ground in front of an altar, a low cylindrical stone with images and hieroglyphs carved on its flat surface.

Stela 16 was found in Twin Pyramid Complex N, placed in front of Altar 5. Offerings of incense, flowers, or even blood would have been placed on the altar and burned as part of rituals. Although it is unclear exactly who would have seen the events recorded on this stela, some Maya sculptures and painted ceramics show nobles in attendance during rituals like this one.

Stela 16 and Altar 5 are no longer arranged as they would have been originally, but they would have looked like these stele and circular altars at Complex Q, Tikal.

The archaeological context of Stela 16—where it was found, and what was found around it—suggests the ritual depicted was related to death as well as time. It stood in front of Altar 5, which is an altar carved in low relief. The altar depicts two individuals on either side of a pile of bones. The individuals are Jasaw Chan K’awiil and the lord of Maasal, a smaller site affiliated with Tikal. The text of the altar describes an event in which people re-entered the tomb of a dead queen. Although this is very different from funerary practice in many places today, tomb re-entry was common for Classic Maya royals. Usually done as a way to honor the deceased individual, it was considered a way to “activate” the legacy and power of the person buried inside the tomb. The pile of bones depicted on the altar was presumably extracted from the tomb of the queen.

Why do we take this scene literally? In part, because archaeologists excavating this part of the complex found a skull and bones underneath Stela 16. These are probably the same bones depicted on Altar 5. From this context, we can understand that the stela and altar worked together to tell viewers that the ritual in which Jasaw Chan K’awiil is participating on Stela 16 was related to time, death, and renewal.

A sensory experience in stone

Stela 16, c. 711 C.E., Classic Period, from the site of Tikal, Guatemala, 3.5 x 1.28 m (photo: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Combined, the various elements recorded on Stela 16 would have created a sensory experience for viewers when they were performed live. The iridescent color of the feathers would have shifted as the king moved in the sunlight, appearing first blue, then green. Viewers would have heard the rustle of feathers and the resonant ringing of jade pieces. They may have smelled incense and listened to the recitation of important texts, histories, and prayers.

Stela 16 recalls those sensory experiences: for the Classic Maya, sculptures were not simple representations. Instead, images could contain part of the k’uh (the vital essence) of the person they represented. Maya viewers would have understood that this image was still active. Not only did the king perform this ritual in 711 C.E., but through his depiction on this stela, he was understood to be perpetually performing it. Sculptures like this one combined religious belief—the idea that specific actions are necessary to maintain world order—with political might. This stela tells us about a specific event in Maya history, but it also reveals how Jasaw Chan K’awiil wished to be remembered: as a powerful and pious king.