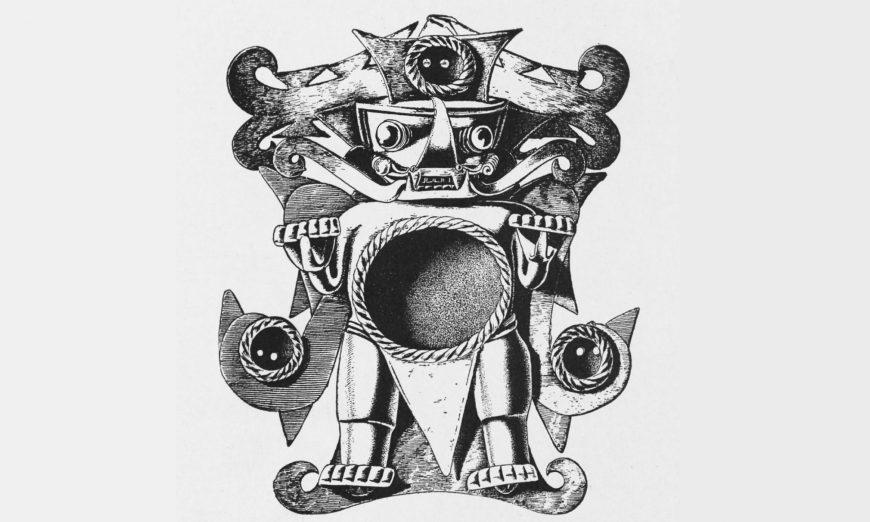

Mirror Pendant in the Form of a Bat-Human, from Grave 5, Sitio Conte, Coclé Province, Panama, gold, c. 850, 3 11/16” x 3 3/16” x 1 1/8” (Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University)

The bat-human pendant is in very good condition overall. One loss can be observed at the right bottom corner and another one can be seen at the left top corner. It is made with a gold-copper alloy (typical of ancient Central American metalwork), and showcases the artists’ skills with a variety of materials and techniques. It was fabricated using the lost-wax method, which requires many steps before the pendant is cast by pouring liquid metal into a mold.

In addition to casting, the curved wings with pointed extensions were made from sheets hammered into shape and attached to the body at the shoulders. Along with casting and hammering, the artists also inlaid materials into the four round and now empty depressions. The inlays have not survived after being buried for centuries in water-logged soil (the cemetery was located along the Great Coclé River). However, archaeologists have observed traces of resin in the large central depression, indicating that some sort of stone was held in place through this method. The other three depressions were inlaid differently, which is indicated by pairs of holes in the metal back.

Such holes would have had a cord pass through the back, holding the stone in place. It is likely that the smaller depressions would have once held pyrite or emeralds. Emeralds were a highly valued material and were used across Mesoamerica and Central America. In fact, a pendant in another Sitio Conte grave has a large square emerald in its back and, as such, bears witness from ancient Panama to the value of greenstone across Mesoamerica and Central America.

Drawing, Grave 5, Sitio Conte, from Samuel Kirkland Lothrop, Coclé: An Archaeological Study of Central Panama, Part I. Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, volume VII (Cambridge: Harvard University Press: 1937), page 104.

On the back of the pendant are two suspension rings, which confirm that this object was designed to be hung on a cord around the neck, either alone, or, more likely, with other pendants such as those found in the grave. There is evidence dating from the time of Spanish Conquest in the 16th century that people living on the Caribbean coast of Panama wore mirrors suspended from their necks.

Iconography

Symbolism

It is not hard to understand why humans create images of themselves possessing the bat’s striking physical features and impressive abilities, such as adroit flight and locating prey at night.

Bat-human imagery in ancient Central American art is often linked to religious beliefs and practices. There is evidence of ritual specialists in ancient Central American societies: men and women who go through rigorous training about the natural and supernatural worlds to gain knowledge that helped them accomplish a goal for the community. The specialists may have animal assistants and they may also transform into these assistants during rituals to acquire the animal’s features and abilities. Beliefs and practices of ritual specialists may also help us understand the pyrite originally in the central depression (and possibly the three smaller ones:) ritual specialists used mirrors like doorways opening into the supernatural realm. Mirrors let them see parts of the universe invisible to the ordinary eye.