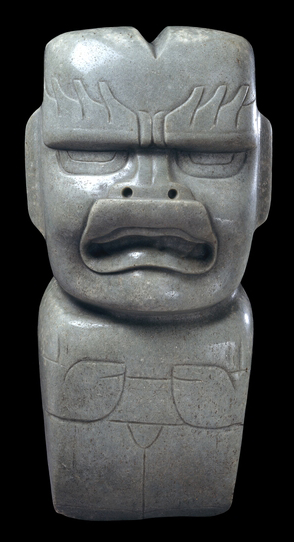

Jade votive axe, 1200-400 B.C.E., Olmec, 29 x 13.5 cm, Mexico © Trustees of the British Museum

Jade votive axe

The Olmec fashioned votive axes in the form of figures carved from jade, jadeite, serpentine and other greenstones. The figures have a large head and a small, stocky body that narrows into a blade shape. They combine features of a human and other animals, such as jaguar, eagle or toad. The mouth is slightly opened, with a flaring upper lip and the corners turned down. The flaming eyebrows seen on this example are also a recurrent feature, and have been interpreted as a representation of the crest of the harpy eagle.

Most axes, including this one, have a pronounced cleft in the middle of the head. This cleft has been interpreted by scholars variously as the open fontanelle (soft spot) on the crown of newborn babies, the deep groove in the skull of male jaguars, or that found on the head of certain species of toads. In some instances vegetation sprouts out of some of them. These combinations of human and animal traits and representations of supernatural beings are common in Olmec art.

Jade perforator

Jade perforator, 1200-400 B.C.E., Olmec, jadite, 38 x 3 cm, Mexico © Trustees of the British Museum

Perforators were used in self-sacrifice rites, which involved drawing blood from several parts of the body. Some representations of Olmec rulers show them holding bloodletters and/or scepters as part of their elaborate ritual costume.

Jade perforator (detail of handle), 1200-400 B.C.E., Olmec, jadite, 38 x 3 cm, Mexico © Trustees of the British Museum

Bloodletting was performed by the ruler to ensure the fertility of the land and the well-being of the community. It was also a means of communication with the ancestors and was vital to sustain the gods and the world. These rituals were common throughout Mesoamerica.Olmec jade perforators are often found in graves as part of the funerary offerings. Bloodletting implements were also fashioned out of bone, flint, greenstones, stingray spines and shark teeth. They vary in form and symbolism. Handles can be plain, incised with a variety of symbols associated to certain deities, or carved into the shape of supernatural beings. The blades, ending in a sharp point, are sometimes shaped into the beaks of certain birds, such as the hummingbird, or into a stingray tail.

This large perforator was probably not used as a bloodletting instrument; it might have been placed in a grave as an offering, or may have served a symbolic function.

Jade pectoral (with Maya glyphs), c. 1000-600 B.C.E., Olmec, Middle Preclassic period, jadeite, 10.5 x 11 cm, Mexico © Trustees of the British Museum

Jade pectoral

This pectoral (chest ornament), broken on both sides, was carved by an Olmec artist and reused by the Maya, as shown by the two Maya glyphs on the left side. The edges framing the head at the top and bottom indicate that it could also have been part of a larger pectoral.

Jade objects in Olmec style have been found throughout Mesoamerica and as far south as Costa Rica. Those found in areas of Mexico, Belize, Guatemala and Honduras, are decorated with different motifs and shapes from those found in the Olmec heartland, centered in present-day Southern Veracruz and Tabasco.

Although contacts between the Maya area and the Olmec heartland seem to have been limited, jade objects in Olmec style appear in Maya deposits dated to the Middle Preclassic (about 1000-400 B.C.E.). Its presence was probably the result of contact between the two areas or with areas that shared the same cultural traditions and similar imagery. Objects found in later deposits, for example at the Cenote of Sacrifice, in Chichen Itza, an Early Postclassic site (900-1200 C.E.), would have been reused over generations or found in earlier graves.

This portrait is a remarkable example of the finest Olmec lapidary art. It was designed to be worn as a pectoral and the pair of Maya name glyphs inscribed on one flange indicate that it was later reused by a Maya lord as a treasured heirloom. Unusually the glyphs are drawn backward so that they face the Olmec portrait, hinting at the power of the object as a symbol of ancestral, dynastic authority. The depressed iris of the eyes and the pierced nose probably bore additional shell work and ornament.

Suggested readings:

Michael Coe, The Olmec World: Ritual and Rulership (Princeton, N.J., Art Museum, Princeton University in association with Harry N. Abrams, 1996).

E. Benson (ed.), The Olmec and their neighbors (Washington, DC, Dumbarton Oaks, 1981).

E. Benson and B. de la Fuente (eds.), Olmec art of ancient Mexico (Washington, National Gallery of Art, 1996).

C. McEwan, Ancient Mexico in the British (London, The British Museum Press, 1994).

© Trustees of the British Museum