Google photosphere of Palenque: view of the Temple of Inscriptions from the Palace

King Pakal and the expansion of Palenque

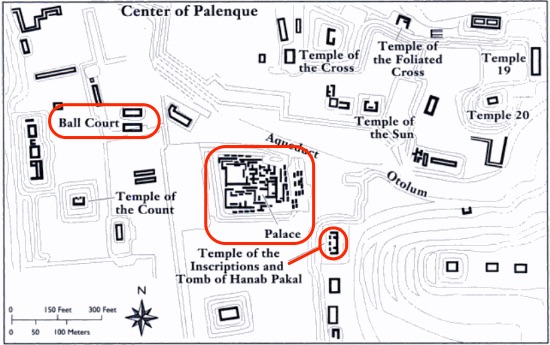

According to Maya glyphic inscriptions, the city of Palenque (in what is today southern Mexico)—comprised of temples, a ballcourt, and the largest surviving Maya palatial complex—was established in 432 C.E. However, it was not until 600-700 C.E. that the city grew in importance. The rule of the king K’inich Janaab’ Pakal, from 615 to 683 C.E., initiated an ambitious architectural expansion at Palenque, an endeavor that was continued by his sons. Local lords such as Pakal, and others like him, each ruled over one of the many Maya city states, each with their own royal court.

The palace complex is located in the center of the city, flanked by the Temple of the Inscriptions and a ballcourt. Both buildings echo the uneven terrain of the Chiapas region, and in some cases they are built into the rolling hills—as in the case of the Temple of Inscriptions.

From: Lynn V. Foster and Peter Mathews, Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 227 (annotated).

King Pakal lived and ruled from the Palace, where various royal ceremonies took place. The unroofed portion to the east of the palace (to the right in the photo below) is believed to be the throne room where kings were crowned. Built like the city, over the course of 200 years and in various stages, the palace features a prominent tower near the center (that scholars believe may have been used as either an observatory or a watchtower).

The Palace, Palenque (photo: Daniel Mennerich, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The roofed portions that remain reveal the typical roof comb architecture of the Maya, most obviously seen in the Temple of the Sun (photo: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0). While the palace occupies a prominent place in the city of Palenque and features a façade with multiple staircases, access to the building was limited and its enclosed spaces purposely guaranteed privacy.

A funerary pyramid

Temple of the Inscriptions, Palenque, Maya, 5th-8th centuries (photo: Carlos Adampol Galindo, CC BY-SA 2.0)

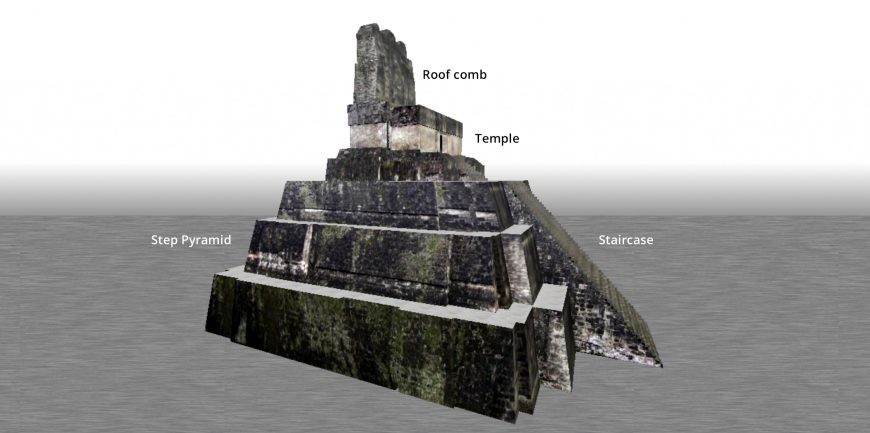

The Temple of the Inscriptions has been called the greatest Maya funerary pyramid and gets its name from the relief panels inside the temple containing an unusually long glyphic inscription that includes a history of the city and its most famous ruler, Pakal (find a translation here). The enclosure at the top was decorated with the iconic Maya roof comb, and decorated with Maya inscriptions.

Diagram of a Maya pyramid (Temple II, 8th century, Tikal), Cyark reconstruction

The pyramid consists of nine levels—the same number of stages found in the Maya underworld (this same numerological association, which was pan-Mesoamerican, is also seen at Temple I in Tikal and El Castillo in Chichen Itza). Long considered a simple pyramid with a temple on top, in 1952, Mexican archeologist Alberto Ruz Lhullier discovered that the Temple of the Inscriptions also contains an interior burial chamber. The tomb of King Pakal is found at the nadir, or lowest point, of the pyramid in a burial chamber that may have once been accessible by an interior stairway but was eventually sealed.

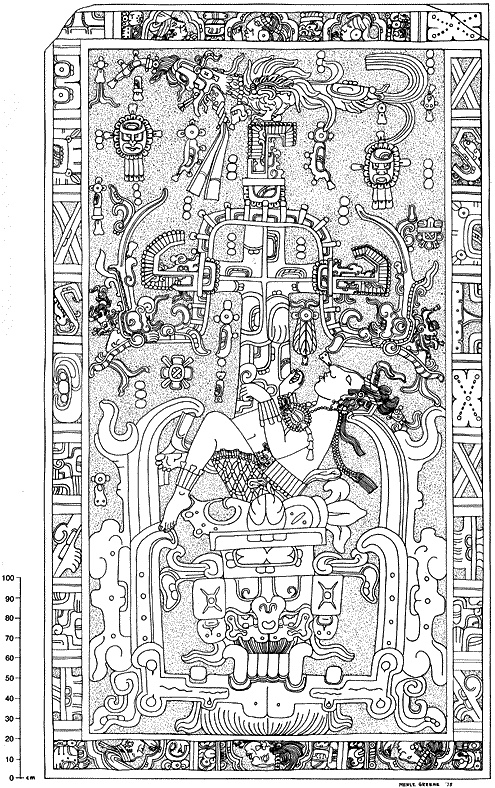

Drawing of the carving on the lid of Pakal’s Tomb, Palenque, Mexico, 5th-8th century CE, Museo Nacional de Antropologia, Mexico City (as drawn by Merle Greene Robertson)

The location of the tomb is significant since King Pakal is buried in a subterranean chamber directly below the pyramid—and is therefore connected to the “earthly” realm. In this way, Pakal inhabits both the world of the living and the dead. The lid of the sarcophagus (a sculpted coffin placed above ground), which was carved out of a single piece of stone features a depiction of the king suspended over the jaws of the underworld (above). On the lid, as in his tomb, Pakal is positioned in an intermediary space, between the heavens—symbolized by the world tree and bird above him—and Xibalba, the Maya underworld.

Portrait Head of Pakal, Palenque, Mexico, c. 650-83, stucco (National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City)

In addition to the remains of Pakal, precious materials such as jade, shells, pearls, and obsidian were discovered inside the sarcophagus. This idealized portrait of Pakal (image left) associates the king with the Maya maize god (his hair is meant to resemble corn silk). It was also found in the tomb and reveals the Maya ideal of beauty, as seen in the king’s oval face, elongated nose, and high cheekbones. His finely sculpted features and realistic portrayal reveal the naturalism of Classic Maya figurative sculpture.

While the tomb of Pakal was largely hidden from view until 1952, archeologists believe that at some point it was made accessible to those who wished to worship the ruler after his death. They also believe that—because construction of the tomb began before Pakal’s death in 683 C.E.—the Temple of the Inscriptions was most likely built to the ruler’s specifications. However, some archaeologists, after studying the skeleton’s teeth, hold that the tomb contains the remains of a man 40 years younger than Pakal—a reminder that Maya archaeology remains a dynamic area of study.

Additional resources: