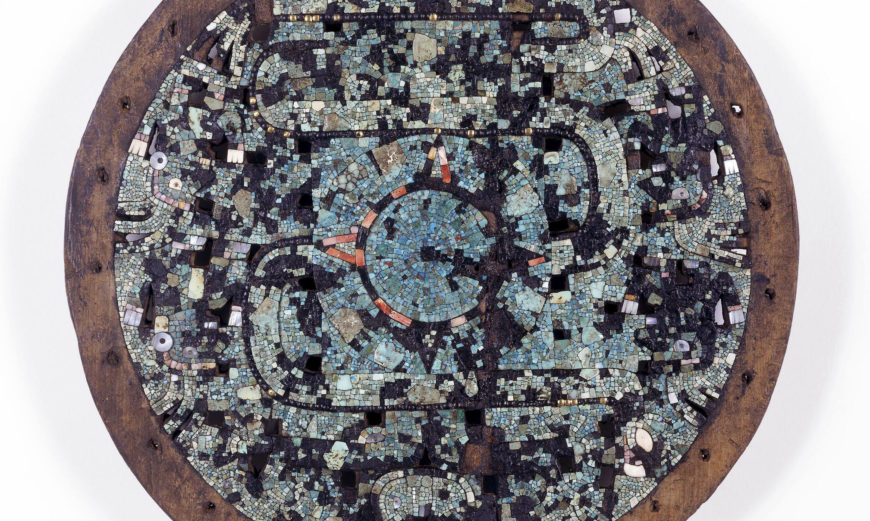

Mosaic serpent mask of Quetzalcoatl/Tlaloc, 15th-16th century C.E., Mexica/Mixtec, cedrela wood, turquoise, pine resin, gold, conch shell, beeswax, 18.2 x 16.5 x 12.5 cm, Mexico © Trustees of the British Museum

Intertwined looped serpents

This mask is believed to represent Quetzalcoatl or the Rain God Tlaloc; both are associated with serpents. The mask is formed of two intertwined and looped serpents worked in contrasting colors of turquoise mosaic; one in green and one in blue that twist across the face and around the eyes, blending over the nose. Turquoise mosaic feathers hang on both sides of the eye sockets. The mask is made of “cedro” wood (Cedrela odorata) with pine resin adhesive. The teeth are made of conch (Strombus) shell and the resin adhesive in the mouth is coloured red with hematite. The rattles of the serpent tails were originally gilded. They are molded from a mixture of beeswax and pine resin; the same resin mixture coats the interior surface of the mask.

The Spanish friar Bernardino de Sahagún, writing in the sixteenth century, describes a mask like this one. It was a gift of the Aztec emperor Motecuhzoma II to the Spanish captain Hernán Cortés (1485-1547). The Aztec ruler thought that Cortés was the god Quetzalcoatl (Feathered Serpent) returning from the East. This mask was part of the adornments associated with this god. According to Sahagún’s description it was worn with a crown of beautiful long greenish-blue iridescent feathers, probably those of the quetzal (a bird that lives in the tropical rain forest).

Side view of mask (detail), Mosaic serpent mask of Quetzalcoatl/Tlaloc, 15th-16th century C.E., Mexica/Mixtec, cedrela wood, turquoise, pine resin, gold, conch shell, beeswax, 18.2 x 16.5 x 12.5 cm, Mexico © Trustees of the British Museum

Quetzalcoatl?

Though the Rain God Tlaloc was also sometimes represented with serpents twisting around his eyes, the feathers are more consistent with the image of Quetzalcoatl. The earliest image of Quetzalcoatl as the Feathered Serpent appears at Teotihuacan in Central Mexico, on the façade of the temple that now bears his name.

Tlaloc?

Close up on eyes of mask (detail), Mosaic serpent mask of Quetzalcoatl/Tlaloc (detail), 15th-16th century C.E., Mexica/Mixtec, cedrela wood, turquoise, pine resin, gold, conch shell, beeswax, 18.2 x 16.5 x 12.5 cm, Mexico © Trustees of the British Museum

The goggled-eyed effect created by the twining serpents is typical of Tlaloc. The mask has also been associated with the feather serpent, Quetzalcoatl, mainly because of the plumes that hang down from the tails of the two serpents. Two serpents of blue and green turquoise mosaic entwine to form this stylized mask. Their interwoven bodies create the prominent twisted nose and goggle eyes associated with Tlaloc, the god of rain. The eyebrows double as the two rattles from the serpents’ tails.

Snakes copulate by intertwining, sometimes in a vertical position. In Mesoamerica, this act of procreation may have been observed and adapted, both visually and metaphorically, to symbolize the fertilizing rains sent by Tlaloc. The striking green and blue colors of the mosaic evoke the waters and vegetation covering the earth’s surface. On the mask’s forehead an engraved mosaic tile in the shape of a bivalve shell may symbolize water, while the large green mosaic tile on the opposite snake perhaps represents vegetation, both aspects associated with Tlaloc. Mosaic representations of feathers flanking the face may have mimicked part of a larger headdress that once complemented the mask.

Open cavities in the eyes and suspension holes indicate that this mask may once have been worn. The priest who served Tlaloc in the Templo Mayor at Tenochtitlan was known as Quetzalcoatl Tlaloc Tlamacazqui, and may have worn a mask like this as part of his ritual attire. Another example of a Tlaloc wooden mask, painted in blue, has recently been excavated from the Templo Mayor. It bears similar perforations and may have been worn by a deity impersonator.

© Trustees of the British Museum