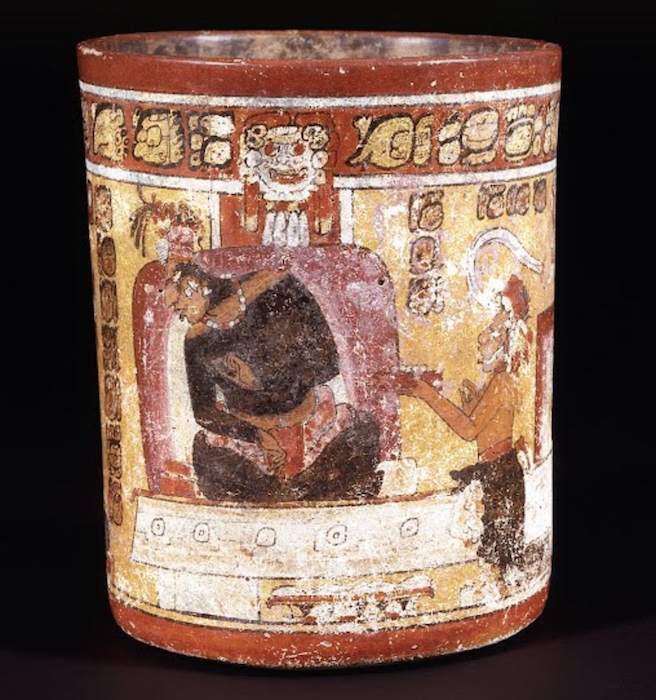

Painted Vessel (Enthroned Maya Lord and Attendants), c. 650-750 C.E., Maya, cylinder vase, ceramic, 16.51 x 20.32 cm (Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C.)

The rich and famous

Getting up close and personal to the rich and famous is not something that many of us have the opportunity to experience in our lifetimes. While we may not be able to rub shoulders with them, television, magazines, and the internet provide us with a glimpse into their lives. Just as media is a form of advertising and communication today, art was a means of communication for the ancient Maya. In a world where most of the population was illiterate, the visual arts were an important tool used to record historical events and communicate political and religious ideals.

Monumental architecture and sculpture of rulers and elites were often set in public spaces for the entire populace to see, as a constant reminder of their control and authority. In restricted elite spaces, which commoners did not have access to, grandiose visual arts were unnecessary signs of wealth. Affluence and authority were instead communicated via much smaller items manufactured from exotic materials by the finest craftsmen. Painted vases were especially favored and were commissioned to portray the lives and activities of those in and around power in the ancient world. These scenes included historical individuals such as the ruler and his family, mystical deities, and natural representations of flora and fauna. They survive today as a visual snapshot into the lives of the rich and famous Maya over 1000 years ago.

The ruler in his court

Ruler sitting with legs crossed and back resting on a large cushion as an attendant offers him a small dish, Painted Vessel (Enthroned Maya Lord and Attendants), c. 650-750 C.E., Maya, cylinder vase, ceramic, 16.51 x 20.32 cm (Dumbarton Oaks Museum)

This painted ceramic, in the collection of the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection in Washington, D.C., shows us an intimate scene involving a ruler and the members of his court. Its style can be dated to the Late Classic period (650-850 C.E.)—a time in which painted ceramics were manufactured in large quantities, many depicting scenes of the royal court.

The ancient Maya were not a unified kingdom but were organized into different city-states, each controlled by a different ruler. The ruler was generally male, although there were a few instances in which there were female Maya rulers. Just as monarchs, prime ministers, and presidents today are supported by an administrative body, ancient Maya rulers were aided by members of their royal court. In addition to providing administrative support, courtiers also provided entertainment for rulers and we see evidence for this in the representation of musicians and dancers on Maya vases.

Two figures (detail), Painted Vessel (Enthroned Maya Lord and Attendants), c. 650-750 C.E., Maya, cylinder vase, ceramic, 16.51 x 20.32 cm (Dumbarton Oaks Museum). Photograph by Alexandre Tokovinine

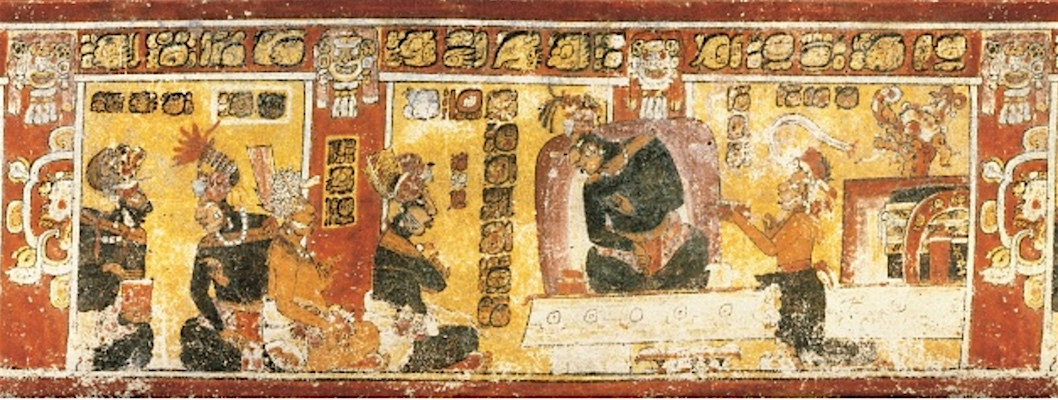

Maya hieroglyphic writing was commonly painted around the rim of vases, to announce its owner and describe the contents inside (frequently a chocolate drink known as cacao). The writing states that the vase is a drinking vessel, belonging to K’ebij Ti Chan (the spelling of this name is uncertain and the first word may have alternatively been K’ebix or Kexik). He was the son of Sak Muwaan (whose name translates as White Bird), ruler of the site Motul de San Jose in Guatemala, whose exact period of reign is unknown but is likely to have been before 701 C.E. or somewhere between 711 and 726 C.E.. K’ebij Ti Chan is not the individual seated on the throne in this scene, but may be the individual seated to the left of the ruler (occupying a privileged position close to the throne). The individual on the throne is a ruler from the Naaman polity, which was based at the site of La Florida. Here is a diagram identifying what we see on the vase.

The importance of the ruler on this vase is emphasized by his placement on a throne, above the other figures in the scene. He sits with his legs crossed and back resting on a large cushion, which is in front of a chest that seems to hold sporting equipment and costume for the ballgame (more about the ballgame here). To his right a kneeling attendant offers him a small dish, perhaps containing food, but the ruler turns away toward the two attendants seated on the ground. Two additional attendants (image left), who may be in a separate room, are seen conversing with each other. Interestingly, three of the attendants are wearing the same body paint as the ruler, and all attendants wear somewhat similar jewelry and accoutrements. The representation of the outfits in this scene is in stark contrast to the large, lavish, outfits depicted on sculpture and other media. This suggests that extravagant outfits were not part of the daily life of the Maya court.

Rollout view, Painted Vessel (Enthroned Maya Lord and Attendants), c. 650-750 C.E., Maya, cylinder vase, ceramic, 16.51 x 20.32 cm (Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection). Image courtesy Justin Kerr.

Hieroglyphics, Painted Vessel (Enthroned Maya Lord and Attendants), c. 650-750 C.E., Maya, cylinder vase, ceramic, 16.51 x 20.32 cm (Dumbarton Oaks Museum)

While excavations have uncovered architectural thrones, demonstrating that rulers did indeed sit on thrones like those depicted in this scene, materials used to manufacture cushions and costume elements are usually not recovered from ancient Maya sites. Unfortunately, because of the humid environment and acidic soils in the Maya region, many organic remains from royal court settings such as this one are not preserved in the archaeological record. Consequently, our knowledge about their use and importance within the court is largely taken from the visual record. Therefore, although this vase is unprovenienced (meaning it was not discovered from a scientifically controlled excavation) it is important to the study of ancient Maya culture and can reveal information about the past that is otherwise unavailable.

How did the Maya make these ceramics?

A cylinder-shaped vase (meaning straight-walled), like this one, was manufactured by hand from local clays available in the Maya region. Recent research shows that these vases were built up from coils placed on top of one another. Once the shape was created, it was left to dry so that it could be painted prior to firing in an open kiln. The Maya obtained different colored pigments from vegetation, minerals, and insects, and applied them using brushes made from hair, fibre, or feathers. Firing the ceramic after painting it ensured a durable, long-lasting, design.

The lack of appendages on cylinder vases required them to be held in both hands, creating a close relationship between object and person. Embellishing the exterior of vases that were in such close contact with the body allowed for an intimate and privileged means of communication. Only a select few individuals would have been privy to holding and viewing vases such as this one. Thus, care was taken to produce painted scenes of the highest quality as a means of impressing whoever came into contact with them. It is likely there were specialized workshops that produced painted vases such as this one, with artists that were in high demand and much sought-after for their skills.

What did the Maya use painted ceramics for?

The Maya used painted ceramics in feasting events to serve food and beverages, and as gifts for elites and rulers from neighboring sites. Feasts were not only a means of celebration and festivity, but were also important political events that fostered relationships between different sites. Ceramics therefore played an important social and political role as objects that were used and gifted. More significantly, the painted scenes that decorated these ceramics became valued elements in their own right and would have stimulated trade between sites that manufactured them, and sites that desired them. Consequently, vases of this kind were used, gifted, and traded between sites all throughout the ancient Maya region.

Presenting food and drink in vases such as this one is akin to serving dinner using the best family tableware, and, presumably, they were afforded the same care and high regard. Many painted vases have been recovered from burials and offerings at archaeological sites, where they were included for their ritual, symbolic, and economic value.

Additional Resources:

This vase at Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

This vase on the Google Art Project (zoomable image)

What can we learn from a Maya vase?

Maya Area, 500-1000 A.D. on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History