Señor de Las Limas, c. 1200–400 B.C.E. (Olmec, Las Limas, Jesús Carranza, Veracruz), serpentine and pyrite, 23 x 43.5 x 55 cm (Museo de Antropología de Xalapa; photo: Jill Mollenhauer)

When you were a child did you ever dream of discovering buried treasure? On July 16, 1965 in the Mexican village of Las Limas, Veracruz, two children did just that. Brother and sister, Severiano and Rosita Manual Pascual, were using a round greenish stone to crack open palm nuts when they decided to take the stone home. Clearing away the earth surrounding the base they were startled to discover that it was, in actuality, the top of a carved human figure. The children had uncovered one of the most beautiful, unique, and ancient examples of the Mesoamerican sculptor’s art, made by a people called the Olmec. The sculpture, now known as the Señor de Las Limas (or Lord of Las Limas), is an example of the earliest known American art style found north of the central Andes. Yet, it continues to pose many questions to researchers that have yet to be answered, hinting at esoteric spiritual knowledge and the divine power held by elite members of the Olmec society.

A dynamic duo

Today, the sculpture greets museum visitors with reflective pyrite pupils flashing in a face sensitively modeled in serpentine, the greenish stone from which it was carved. The primary human figure is seated cross-legged, holding a smaller figure which lies prone in a horizontal position across its lap. The human is male, as indicated by his maxtlatl (loincloth). His body is simply modeled with the organic, curved forms and monumental volume typical of Olmec-style sculpture.

Head (detail), Señor de Las Limas, c. 1200–400 B.C.E. (Olmec, Las Limas, Jesús Carranza, Veracruz), serpentine and pyrite, 23 x 43.5 x 55 cm (Museo de Antropología de Xalapa; photo: Jill Mollenhauer)

The face is carved with more detail and naturalism, represented as youthful and idealized. The almond-shaped eyes and delicate lips, slightly parted to reveal the upper row of teeth, are the most deeply sculpted areas of the face. In contrast, the ears are more abstract and stylized, with sinuous incisions merely hinting at the complex curvature of the auricle. The hair is also simplified, represented as a smooth cap distinguished from the rest of the head by a raised edge representing the hairline, which comes together in a triangular peak at the center of the forehead. The shoulders, knees, and face of this central figure are incised with esoteric spiritual designs, discussed in more detail below.

Smaller figure (detail), Señor de Las Limas, c. 1200–400 B.C.E. (Olmec, Las Limas, Jesús Carranza, Veracruz), serpentine and pyrite, 23 x 43.5 x 55 cm (Museo de Antropología de Xalapa)

Monument 52, c. 1200–850 B.C.E. (Olmec, San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, Veracruz), basalt, 91.9 cm high (Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City)

The smaller figure, held prone in the human’s arms, has the features of an Olmec supernatural—perhaps a spirit or deity—sometimes erroneously referred to as a “were-jaguar.” These features include almond-shaped eyes, a broad nose, and a large, down-turned mouth with flared top and bottom lips pulled back to reveal toothless gums. The creature sports a V-shaped cleft or indentation at the back of its head, a feature frequently seen on Olmec supernaturals of this type. It wears a banded headdress with incised designs that might represent cords and/or knots. Extending down to frame its face are accordion-like folds of what might be cloth or paper, similar to those appearing on other Olmec figures (such as Monument 52 from the nearby Olmec center of San Lorenzo). On its chest it wears a pectoral or plaque decorated with crossed-bands. At the center of its torso, it wears another plaque or perhaps a belt ornament with the same crossed-bands, this one bordered on top and bottom with a saw-tooth motif. Crossed-bands are repeated frequently as a key symbol or motif in Olmec art, although their significance remains a subject of intense scholarly speculation.

Altar 5, from Complex A, La Venta, c. 700–400 B.C.E. (Olmec), basalt, 91 x 73 x 77 cm (Parque Museo La Venta, Villahermosa; photo: @Abel_MenaHis)

Similar figures are held in the arms of humans sculpted on several of the monumental Olmec thrones. Altar 5 from La Venta is decorated with relief carvings of four such creatures being held (some seeming to struggle or wriggle like cranky toddlers) in the arms of Olmec elites. The latter’s status and identities are indicated by their elaborate headdresses. These human figures are seated cross-legged in pairs along the throne’s sides, all facing towards the central figure (perhaps a ruler) who is seated in the frontal niche. In his arms he holds another supernatural being in a horizontal position akin to that of the Las Limas figure. The rounded niche in which he is seated most likely represents the mouth of a cave. Later Mesoamerican cultures viewed caves as spiritually potent places of ritual—the dwellings of ancestors and the gods or spirits who control rain and agricultural production. The bringing forth of cave-dwelling supernaturals who lie limp and complacent in the central lord’s outstretched arms may represent the Olmec elites’ control over the spiritual forces of nature.

A paradox of Olmec style

The Las Limas sculpture was produced by an artist or artists in a style we now call Olmec.

Map of Olmec population centers (photo: Minerva Magazine)

The archaeological culture of the Gulf Coast Olmec was located in what is now southeastern Mexico, with major population centers extending from the Tuxtla Mountains of southern Veracruz to the north-western region of Tabasco’s Grijalva river delta. The term “Olmec” is also used to describe an art style associated with these people, although variations of the style are found far and wide in Mesoamerica throughout the Early (c. 2000–850 B.C.E.) and Middle (850–350 B.C.E.) Formative periods, from Guerrero in the east to Morelos in the north and as far south as Honduras, El Salvador, and even Costa Rica.

The style of the Las Limas figure is typical of Olmec sculpture from the Gulf Coast region, which is notable for its swelling volumes, rounded forms, and harmonious proportions. Single figures are symmetrically balanced. Facial features display a sensitive naturalism and the visual emphasis is typically placed on the head, face, and costume elements, created through proportion and detailing. The rest of the body is typically rendered with smoothed, simplified anatomical forms. As with the Las Limas sculpture, humans and supernaturals carved in stone are relatively asexual in their overall appearance, although subtle visual cues and costume elements (such as the Las Limas human’s maxtlatl) can provide important clues to a figure’s gender.

The creators of Olmec figurative art balanced its tendency towards naturalism with abstraction by carving in relief or lightly inscribing two-dimensional patterns and symbols over the three-dimensional forms, juxtaposing the primary figure’s visibility with subtle layers of nearly invisible, culturally-encoded symbolism. Many of these incised designs include esoteric features and supernatural faces that suggest a spiritual or mythological realm lurking just under the surface of the visible world. This play between the seen and the unseen is a frequent theme cultivated by the Olmec in both their art and architecture.

Incised mask from Arroyo Pesquero, Veracruz, c. 850–400 B.C.E. (Olmec), greenstone (Museo de Antropología de Xalapa; photo: Jill Mollenhauer)

Yet, while the Lord of Las Limas exemplifies many of the characteristics of the Olmec artistic style, it is also a highly unusual sculpture. The subject of a human lord or priest holding a spirit being is well-known from other examples of Olmec monumental art (as discussed above). However, these are sculpted as a part of the decoration on table-top thrones carved of basalt. And while incised symbolism is common, it is usually found on small portable sculptures carved of greenstone, primarily taking the forms of figurines and masks (see for example the mask from Arroyo Pesquero above). In contrast, the Las Limas sculpture combines a subject found on monumental seats of power and authority (table-top thrones) with the material and incising typical of smaller, more personal objects of ritual. The scale of the object also sits somewhere between monumental and portable (measuring 55 cm high by 43.5 cm wide) and spaces between the human’s arms and torso could have been used to wrap a rope or tumpline around the sculpture for easy transport. It is quite possible that the sculpture was treated as a portable object of veneration, perhaps regularly moved from one site or shrine to another.

Señor de Las Limas, c. 1200–400 B.C.E. (Olmec, Las Limas, Jesús Carranza, Veracruz), serpentine and pyrite, 23 x 43.5 x 55 cm (Museo de Antropología de Xalapa; photo: Jill Mollenhauer)

Making the invisible visible

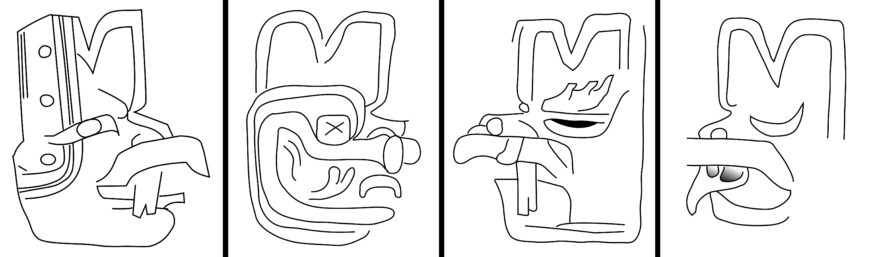

The incised markings on the Las Limas figure’s shoulders, knees, and face are also unique in their combinations, although many of the individual motifs and symbols are familiar from other examples of Olmec art. The supernatural faces inscribed on shoulders and knees have been the subject of much debate, although there is general agreement that their features and cleft heads mark them as supernatural beings related to Olmec mythology or religious beliefs. Various scholars have attempted to identify these beings as part of a pantheon of Olmec deities or spirits, although it is also possible that they are different manifestations of a single divine force. Some of them are recognizable from their appearance in other contexts, including a spirit identified with the earth, sometimes called the “Olmec dragon” (right knee) and the “shark-” or “fish-monster” (left knee). The left shoulder is inscribed with a creature combining bird, jaguar, and reptilian features, while the right shoulder is marked with the head of an unidentified being with a curving band under its eye. Together with the three-dimensionally sculpted being held at the center of the composition, these inscribed faces create a cosmogram in the form of a quincunx, a symbol representing the five-part division of the world.

Incised representations of Olmec supernaturals, from left to right: right shoulder; right knee; left shoulder; left knee (photos: Madman2001, CC BY-SA 2.5)

Although their identities remain speculative, these heads clearly mark the spiritual nature of the sculpture, as do the inscribed symbols that cover the face of the human figure. These facial motifs (possibly representing tattoos, body paint, or scarification) create a buccal mask covering the lower face of the figure. Rectilinear cleft symbols, similar in overall form to the cleft heads on shoulders and knees, are inscribed above the eyes along the brow ridge, while more linear and cleft motifs frame the face on either side. Taken together, they transform the youthful, idealized human face into a supernatural visage, perhaps a visible manifestation of an otherwise invisible spiritual power accessed via ceremony and ritual performance.

These inscribed designs provide a layer of esoteric information that would only be available to viewers upon very close inspection, perhaps even indiscernible in some lighting conditions and only known to (or understood by) the initiated. Given the scale and difficulty in perceiving the inscribed imagery, it is likely that the sculpture was intended for a more private viewing experience by a select few, rather than a larger space of public display. Even millennia after its makers have gone, and with them their myths and rituals, the Lord of Las Limas—with its reflective pyrite eyes, body of luxurious greenstone, and esoteric inscriptions—allows us to rediscover a sense of the power and mystery that must have similarly affected its onlookers in the ancient past.

Additional resources

This work at the Museo de Antropología de Xalapa

Olmec Art on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Kathleen Berrin and Virginia M. Fields, editors, Olmec: Colossal Masterworks of Ancient Mexico, exhibition catalogue (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2010).

Julia Guernsey, John E. Clark, and Barbara Arroyo, editors, The Place of Stone Monuments: Context, Use, and Meaning in Mesoamerica’s Preclassic Transition (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2010).

Alfonso Medellín Zenil, “La Escultura de Las Limas,” Boletín del Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, number 21 (1965), pp. 5–8.

Christopher A. Pool, Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2007).