Prehistoric art around the globe

When we think about prehistoric art (art before the invention of writing), likely the first thing that comes to mind are the beautiful cave paintings in France and Spain with their naturalistic images of bulls, bison, deer and other animals. But it’s important to note that prehistoric art has been found around the globe—in North and South America, Africa, Asia, and Australia—and that new sites and objects come to light regularly, and many sites are just starting to be explored. Most prehistoric works we have discovered so far date to around 40,000 B.C.E. and after.

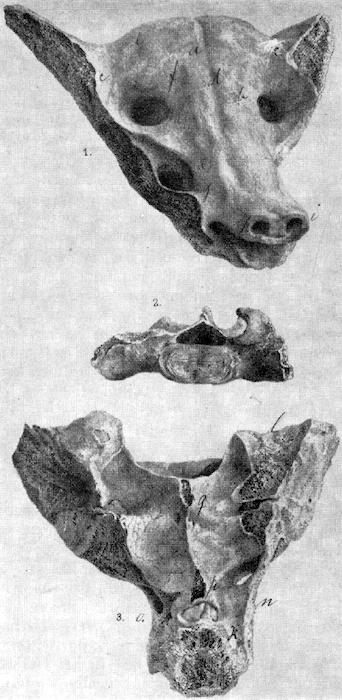

Lithograph of the sacrum as illustrated by Mariano Bárcena, published in Anales del Musei Nacional, volume 2 (1882)

This fascinating and unique prehistoric sculpture of a dog-like animal was discovered accidentally in 1870 in Tequixquiac, Mexico—in the Valley of Mexico (where Mexico City is located). The carving likely dates to sometime between 14,000–7,000 B.C.E. An engineer found it at a depth of 12 meters (about 40 feet) when he was working on a drainage project—the Valley of Mexico once held several lakes. The geography and climate of this area was considerably different in the prehistoric era than it is today.

What is a camelid? What is a sacrum?

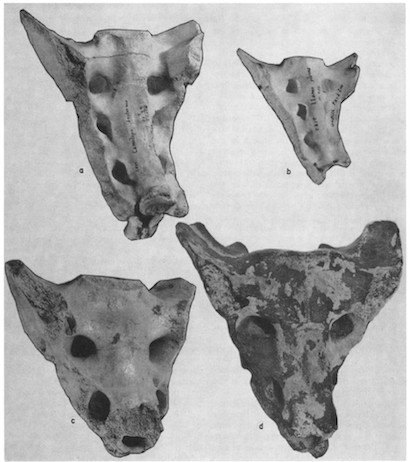

The sculpture was made from the now fossilized remains of the sacrum of an extinct camelid. A camelid is a member of the Camelidae family—think camels, llamas, and alpacas. The sacrum is the large triangular bone at the base of the spine. Holes were cut into the end of the bone to represent nostrils, and the bone is also engraved (though this is difficult to see in photographs).

Issues

The date of the sculpture is difficult to determine because a stratigraphic analysis was not done at the find spot at the time of discovery. This would have involved a study of the different layers of soil and rock before the object was removed. Another problem is that the object was essentially lost to scholars between 1895 and 1956 (it was in private hands).

In 1882 the sculpture was in the possession of Mariano de la Bárcena, a Mexican geologist and botanist, who wrote the first scholarly article on it. He described the object in this way:

“…the fossil bone contains cuts or carvings that unquestionably were made by the hand of man…the cuts seem to have been made with a sharp instrument and some polish on the edges of the cuts may still be seen…the articular extremity of the last vertebra was utilized perfectly to represent the nose and mouth of the animal.” [1]

Bárcena was convinced of the authenticity of the object, but over the years—due to the lack of scientific evidence from the find spot—other scholars have questioned its age, and whether the object was even made by human hands. One author, in 1923, summarized the issues:

To allow us to state that the sacrum found at Tequixquiac was a definite proof of ancient man in the area the following things must be proven: (1) That the bone was actually a fossil belonging to an extinct species. We cannot doubt this since it has been affirmed by competent geologists and paleontologists. (2) That it was found in a fossiliferous deposit and that it had never been moved since it found its place there. This has not been proved in any convincing manner. (3) That the cuttings of the bone can actually be attributed to the hand of man and that it can never have occurred without human intervention. This has not been proved either. (4) That the carving was made while the species still existed and not in later times when the bone had already become fossilized. [2]

Today, scholars agree that the carving and markings were made by human hands—the two circular spaces that represent the nasal cavities were carefully carved and are perfectly symmetrical and were likely shaped by a sharp instrument. However, the lack of information from the find spot makes precise dating very difficult. It is quite common, in prehistoric art, for the shape of a natural form (like a sacrum) to suggest a subject (dog or pig head) to the carver, and so we should not be surprised that the sculpture still strongly resembles a sacrum.

Sacra from various forms of camel, illustration from: Luis Aveleyra Arroyo de Anda, “The Pleistocene Carved Bone from Tequixquiac, Mexico: A Reappraisal,” American Antiquity, volume 30, (January 1965), p. 269

Interpretation

Because the carving was made in a period before writing had developed, it is likely impossible to know what the sculpture meant to the carver and to his/her culture. One possible way to interpret the object is to look at it through the lens of later Mesoamerican cultures. One anthropologist has pointed out that in Mesoamerica, the sacrum is seen as sacred and that some Mesoamerican Indigenous languages named this bone with words referring to sacredness and the divine. In English, “sacrum” is derived from Latin: os sacrum, meaning “sacred bone.” The sacrum is also—perhaps significantly for its meaning—located near the reproductive organs.

“Language and iconographic evidence strongly suggests that the sacrum bone was an important bone indeed in Mesoamerica, relating to sacredness, to resurrection, and to fire. The importance attached to this bone and its immediate neighbors is not limited to Mesoamerica. From ancient Egypt to ancient India and elsewhere, there is abundant evidence that the bones at the base of the spine, including especially the sacrum, were seen as sacred.” [3]

As appealing as this interpretation is (and the argument the author makes is quite convincing), it is wise to be wary of connecting cultures across such vast geographic distances (though of course there are some aspects of our shared humanity that may be common across cultures). At this point in time, we have no direct evidence to support this interpretation, and so we can not be certain of this object’s original meaning for either the artist, or the people that produced it.

Notes:

[1] As quoted in Luis Aveleyra Arroyo de Anda, “The Pleistocene Carved Bone from Tequixquiac, Mexico: A Reappraisal,” American Antiquity, volume 30, (January 1965), p. 264.

[2] As quoted in Luis Aveleyra Arroyo de Anda (January 1965).

[3] Brian Stross, “The Mesoamerican Sacrum Bone: Doorway to the otherworld,” FAMSI Journal of the Ancient Americas (2007) pp.1–54.

Additional resources

Luis Aveleyra Arroyo de Anda, “The Pleistocene Carved Bone from Tequixquiac, Mexico: A Reappraisal,” American Antiquity, volume 30, (January 1965), pp. 261–77.

Paul G. Bahn, “Pleistocene Images outside of Europe,” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, volume 57, part 1 (1991), pp. 91–102.

Brian Stross, “The Mesoamerican Sacrum Bone: Doorway to the otherworld,” FAMSI Journal of the Ancient Americas (2007), pp.1–54.