Mission San Agustín de la Isleta and houses, Isleta Pueblo (photo: MARELBU, CC BY 3.0)

Until relatively recently, houses at the Southern Tiwa Pueblo of Isleta in New Mexico were replastered every year using a mixture that contained mica from a culturally significant site in the southwestern United States. In the bright sunlight of the southwest, mica’s natural shimmer adds a reflective, lustrous quality to these homes. Yet using the mica to create this shimmering quality was not done simply because it is pleasing to look at, but because its appearance paralleled the transformative qualities that feature so prominently in Pueblo stories and songs. It is one of the many ways that Pueblo architecture reveals a close connection to the surrounding landscape and to Pueblo culture.

Pueblo people

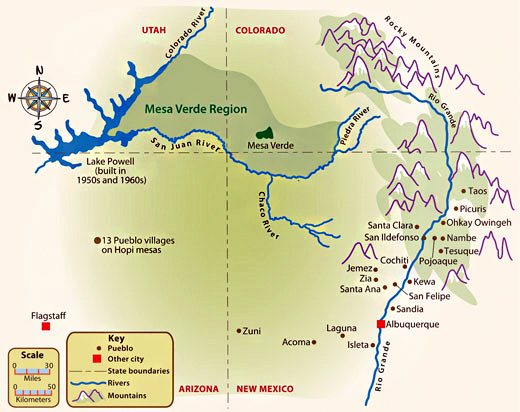

The Pueblo people are one of many Native American cultural groups living in the southwestern United States. Contemporary Pueblo villages are located throughout the north-central and western regions of New Mexico and in northeastern Arizona and are often broadly divided into two distinct geographical groups. These include:

- the Eastern (or Rio Grande) pueblos of Cochiti, Isleta, Jemez, Nambe, Ohkay Owingeh, Picuris, Pojoaque, Sandia, San Felipe, Santa Ana, Santa Clara, Santo Domingo, Taos, Tesuque, and Zia; and

- the Western pueblos of Acoma, Laguna, Zuni, and villages of the Hopi Mesas.

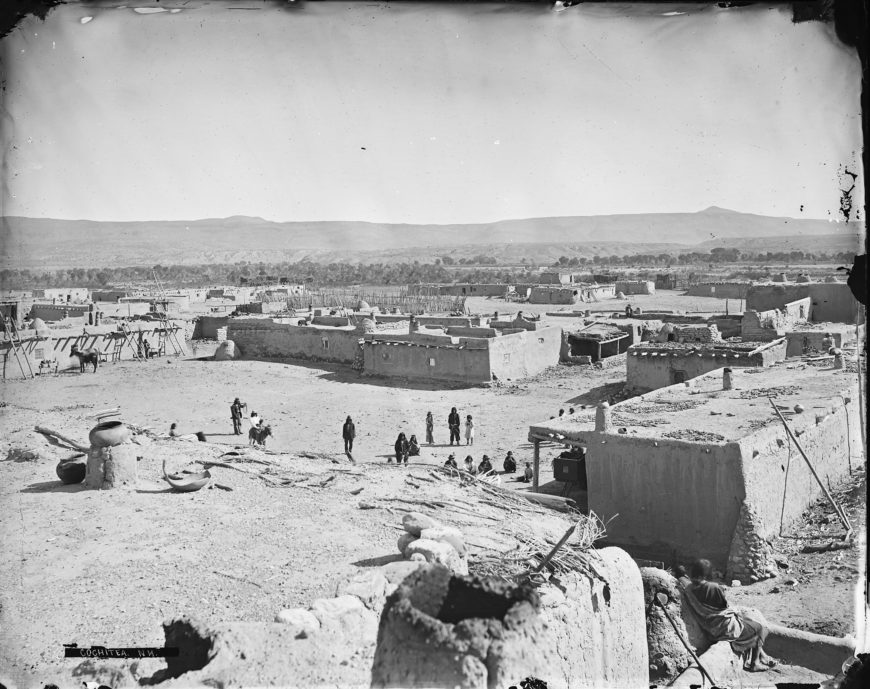

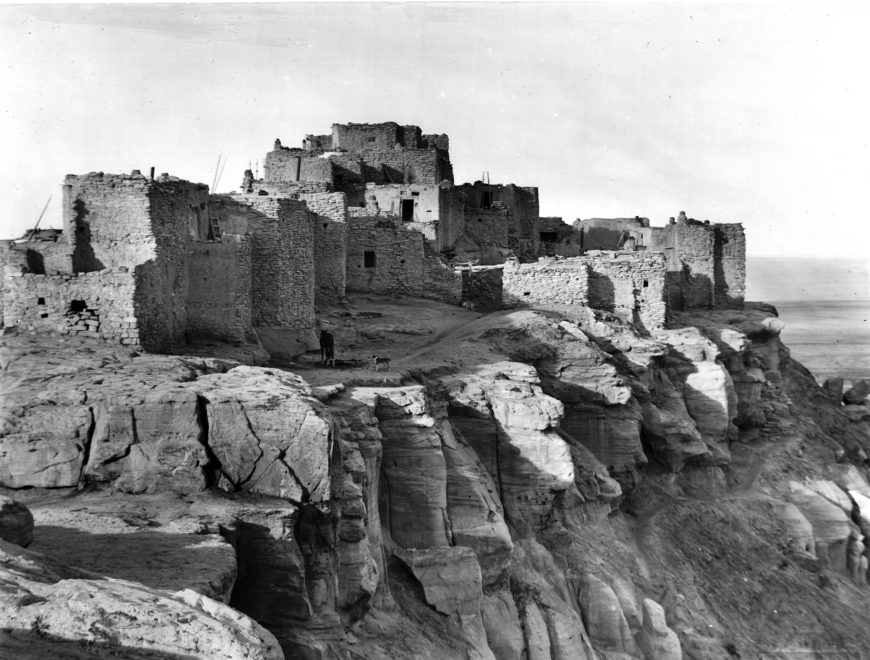

Cochiti pueblo, c. 1871–1907, photo by John K. Hillers, Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology (National Archives at College Park)

In addition to referring to the Pueblo people, the word “pueblo” is Spanish and means “town.” In this context it refers to the shared architectural style that early Spanish colonists encountered in many of the villages in the region (after they began colonizing the area after the late 16th century). While people living in Pueblo villages share a common form of architecture and communal life, as well as overlapping ancestries, they are also quite diverse—culturally, ethnically, and linguistically. Although interrelated, distinct customs and forms of social organization are found within the various Pueblo villages. Individuals’ participation in various social groups may reflect familial ties, ceremonial responsibilities, access to ritual knowledge, gender affiliations, and differences in migration histories and relationships to place. Throughout their lifetimes, Pueblo community members are affiliated with various social and ritual groups, frequently spanning across multiple villages.

Rock art at Petroglyph National Monument, New Mexico (photo: Mobilus In Mobili, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Some contemporary Pueblo villages have been occupied continuously for a period of 1,000 years or longer. Ancestral Pueblo occupation within the larger region extends back even further. We know this through both Puebloan oral tradition and archaeological sites—better referred to as “footprints”—that dot the landscape throughout the region. Examples of such “footprints” include rock art sites and ancestral villages that are no longer actively occupied but embody traces of the ancestors who came before.

Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico (photo: Paul Williams, CC BY-NC 2.0)

A powerful example of such a “footprint” is the ancestral site of Pueblo Bonito, one of the “Great Houses” of the Chaco Canyon cultural area in northwestern New Mexico. Construction began on Pueblo Bonito in approximately 850 C.E. and continued, in stages, until approximately 1150 C.E. The sheer enormity of Pueblo Bonito and the richness of the archaeological record at the site indicate that it was an important ceremonial center for a period of approximately three hundred years, and it remains a culturally and spiritually significant site for Pueblo people today.

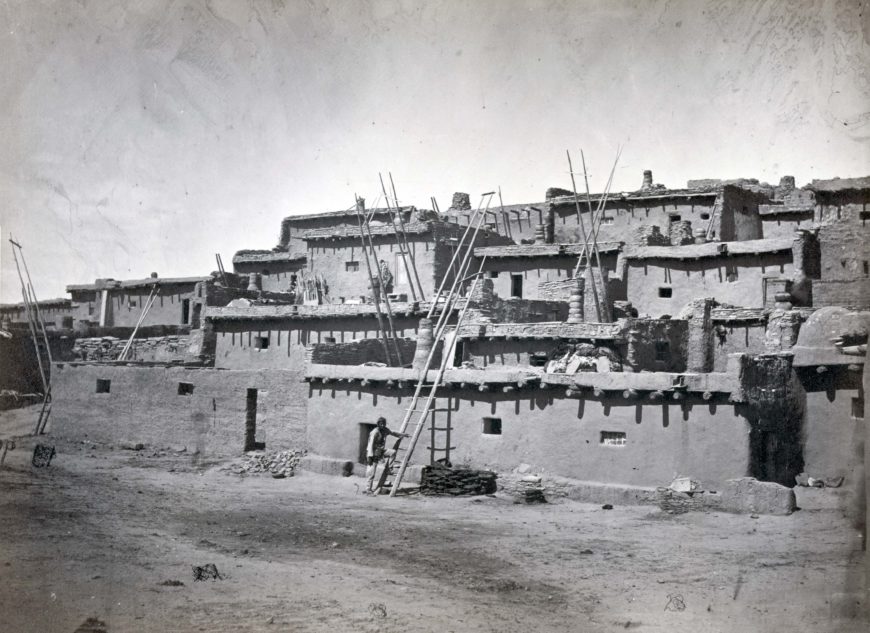

Large multi-level buildings of the south side of Zuni Pueblo, c. 1873, photograph by Timothy O’Sullivan (Library of Congress)

Main characteristics of Pueblo architecture

Characteristics of Pueblo architecture include large multi-level buildings, numerous contiguous rooms (rooms that touch one another or share a boundary wall), terraced design, and open-air plazas. Traditional Pueblo architectural design did not include doors, and in traditional buildings, each level was accessible by exterior and interior rooftop ladders. Contemporary Pueblo villages incorporate modern architectural elements and infrastructure (such as electricity, plumbing, glass windows, and exterior doors).

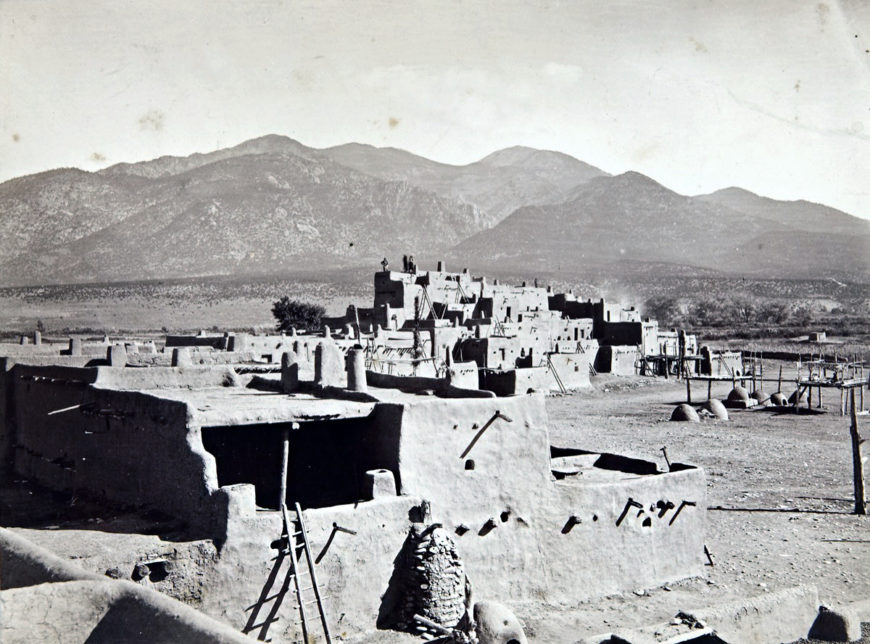

Terraced design at Taos Pueblo, 1880, photograph by Johannes Karl Hillers (Pitt Rivers Museum)

Late 19th-century photographs of Zuni and Taos Pueblos show many ladders raised against the walls of multi-leveled adobe buildings, as well as ladders emerging from interior rooms. We see the same design feature today at Acoma Pueblo.

Acoma Pueblo street with contiguous rooms in adobe buildings and ladders that lead to the upper story entrances to kivas (sacred ceremonial spaces; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Contiguous rooms have many different uses, both public and private, and they are easily accessed via the ladders. Outer rooms, terraces, and other accessible rooms were used as common living spaces. Lower levels, interior rooms, and other more difficult-to-reach rooms were used for food storage and ceremonial purposes.

Open-air plaza at Acoma Pueblo (photo: osseous, CC BY 2.0)

Plazas and kivas

Open-air plazas and terraces are significant architectural components in Pueblo villages. They served as sites for participation in public ritual and also facilitated multiple forms of daily household and village activities, such as harvest storage (as we see in the photograph of Santa Clara Pueblo), food preparation, and ceramics production.

Acoma Pueblo street ladders that lead to the upper story entrances to kivas (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-SA 2.0)

In each Pueblo, various groups are responsible for the performance of culturally significant activities in accordance with the ceremonial calendar. Activities include public components such as songs and dances that take place in the village plazas and private components that take place within the kivas. Kivas are ceremonial structures, usually located in close proximity to the open-air plazas. Access to kivas is restricted to community members with the appropriate cultural and ritual authority to enter those spaces. Although many modern kivas may be built into the architecture of the contiguous surface room blocks or as free-standing structures, many ancestral kivas were built as subterranean or semi-subterranean spaces.

In the Pueblo world, a sense of place is connected to emergence and movement, an idea that Pueblo architectural forms embody. For example, rooftop entrances to kivas reinforce Pueblo cosmological ideas (or a knowledge system that explains the origin, development, and structure of the universe) about emergence and return. During special ceremonial performances, audience members can watch performances unfold from the terraces above rooms where kivas are located, yet performers may also emerge from upper-level terraces onto the plaza below. Similarly, the dances that are performed in the village plazas may reference movement and migration across the ancestral landscape.

Movement and the search for the middle place

Origin stories emphasize a long tradition of movement as the ancestors emerged from the underworld and searched for their “middle place,” the place where they were destined to live and perpetuate their cultural teachings. Mobility was characteristic of early Pueblo cultures as families and other small groups moved across the landscape, over the course of many generations. Santa Clara Pueblo scholar Tessie Naranjo writes that “the old people moved continuously, and that was the way it was.” Movement within fixed boundaries is a fundamental element of Pueblo thought and being and, she continues, “even these specific boundaries are not the important elements because as the people moved, their mountain boundaries also moved. The idea was to have boundaries to create a place—to fix a place—temporarily within a larger idea of movement.” [1]

Hopi Pueblo of Walapi (or Walpai) on mesa, c. 1901, photo by Charles C. Pierce (USC Libraries Special Collections)

The Tewa speak of two groups moving for many years along two mountain ranges before joining together to form one village. The Zuni speak of building villages in which to live for a period of four days and four nights, a phrase that may mean four years, four hundred years, or four thousand years. The Hopi speak of an ancestral promise to make footprints on their way to becoming Hopi. Pueblo ancestors carried a sense of cosmological place and situated-ness with them wherever they went on their path to the “middle place.”

Construction materials

WPA workers make adobe bricks, Santa Fe, New Mexico, June 1940 (National Archives and the New Deal Network)

Materials used in the construction of Pueblo architectural forms include clay, sand and silt, grasses and reeds, water, stone, and timber. Although building materials are often locally sourced, some materials travel great distances.

Depending upon availability, Pueblo room blocks are built using either sun-dried adobe or stone masonry, and sometimes both. Adobe is made from a mixture of clay, sand or silt, straw, and water, and is often formed into bricks that are held in place with a clay-based mortar. Stone masonry technology also employs mortar.

Core-and-veneer stone masonry technique of multistoried rooms, Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico (photo: (photo: Jacqueline Poggi, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0); right: detail of the masonry (photo: Lars Hammar, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The Ancestral Pueblo sites of Pueblo Bonito and Chetro Ketl at Chaco Canyon were built using a highly refined core-and-veneer stone masonry technique in which coarsely cut stones form the interior (or core) of a wall and finely shaped and fitted stones form the exterior (or veneer) of a wall. Extraordinary surface patterns are also made possible with such a technique. The stone walls built during the period of Chaco’s cultural heyday were covered in plaster.

Structures built using traditional Pueblo techniques are replastered each year to maintain their structural integrity. In a 1940 photograph of Chamisal we see a group of people in the process of replastering a wall.

Buildings with vigas projecting outwards, Acoma Pueblo (photo: Beyond My Ken, CC BY-SA 4.0)

While adobe and stone are used to build the vertical walls of Pueblo rooms, long lengths of timber known as vigas provide the horizontal stability necessary to support a room’s ceiling and multi-level construction. Spaced at regular intervals, vigas span a roomblock front to back and are visible from the exterior of the building, such as we see at Acoma Pueblo. Wooden slats called latillas are placed in a crosswise layer above the vigas, and together these components form the foundation for the floor or terrace above and transfer the weight to the outer load-bearing walls. In the arid climate of the Pueblo landscape, transporting trees over long distances is quite laborious, and the archaeological record reveals evidence of viga re-use as well.

Lumber is often not the only material to travel great distances. Family and clan lineages often develop special “recipes” for paint, plaster, adobe, and other components, and individuals may travel great distances to collect the necessary materials. A particular material may be important because of its association with an origin or migration story. Similarly, the materials found at a particular place in the landscape could be understood to have transformative or otherwise powerful qualities. Incorporation of these materials into Pueblo architectural forms imbues structures with their particular powers.

Mica, quartz, feldspar, and selenite are minerals that appear in ancient rocky outcroppings and other sites throughout the Puebloan cultural landscape. Highly reflective in nature and often appearing to shimmer and move in the abundant sunlight of the Southwest, such minerals are highly valued within a Pueblo cultural context for their transformative qualities—qualities that also describe many of the doings in Pueblo stories and songs. Customarily, only individuals with the appropriate knowledge and permission may collect and process such powerful and “lively” materials for use in special clay, paint, and plaster recipes.

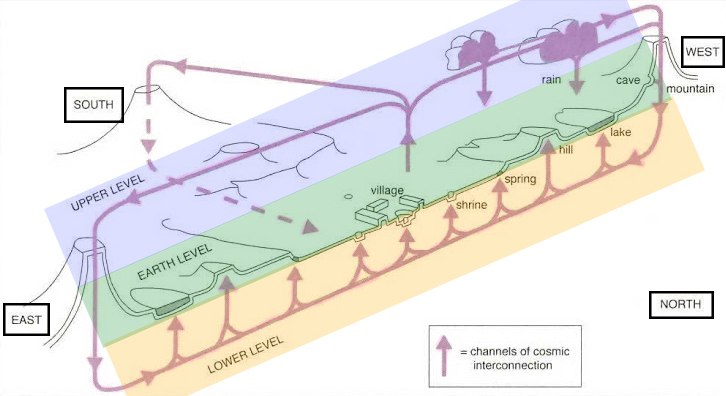

Depiction of the Pueblo cosmos showing its interconnectedness. Diagram modified from Severin M. Fowles, An Archaeology of Doings: Secularism and the Study of Pueblo Religion (Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press, 2013), Figure 5.12 (adapted from Saile 1990, based on Ortiz 1969)

A conceptual understanding of a Pueblo village

Metaphor is fundamental to Pueblo thought and being, and an understanding of the universe as a web of lively, dynamic, and interconnected beings are vital components of Pueblo architectural forms. The lower half of the Pueblo cosmos is often envisioned as a terraced bowl (the earth) with another bowl (the sky) inverted atop it. Together, the two bowls form the sphere of the universe within which all activity transpires. Naranjo writes:

All existence swirls around the center. The houses of the people, the hills, and mountains are in concentric circles around the center place. The sky and earth define the sphere within which the center is crucial to the orientation of the whole. The breath of the universe passes through this center place as did our people when they emerged into this level of life. [3]

The spatial organization of a typical Pueblo village is arranged to reflect the structure of the universe and to symbolize the ancestral search for the middle place. Located within the central village plaza is a small hole, or “earth navel,” that is considered to be the “true center of the village.” (Photographs are not permitted). Although often quite inconspicuous visually, the plaza earth navel functions as the site of the axis mundi—a sacred site of both emergence and return that joins the underworld, the middle place, and the upper world.

Connecting the village with the surrounding landscape, the plaza earth navel is nested within a landscape marked by other earth navels. Each earth navel designates a sacred shrine, hilltop, or mountaintop that corresponds to one of the four cardinal directions. Marked by a loose arrangement of stones forming an open keyhole shape pointing toward the village, these earth navels direct blessings inward, toward the village. Blessings arrive in the form of rain and a bountiful harvest. The village earth navel, on the other hand, is marked by a loose arrangement of stones forming a circle open on all sides to the earth navels surrounding the village, directing blessings outward and thereby ensuring that all sacred energy remains within the landscape. [4] Just as each village’s point of emergence is considered to be the true place of origin, so, too, is each village considered to be the true middle place. Rather than contradicting one another, however, Pueblo stories of emergence and migration both honor and reiterate the idea of multiple centers.

Notes:

[1] Tessie Naranjo, “Thoughts on Migration by Santa Clara Pueblo,” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 14 (1995), 247–249.

[2] Janet Catherine Berlo and Ruth B. Phillips, Native North American Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 28.

[3] Tessie Naranjo, Wall text from the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture exhibition, “Here, Now, and Always,” 2018.

[4] Alfonzo Ortiz, The Tewa World: Space, Time, and Becoming in a Pueblo Society (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1969), pp. 19–21.

Additional resources

Read more about Pueblo architecture from the New Mexico Museum of Art