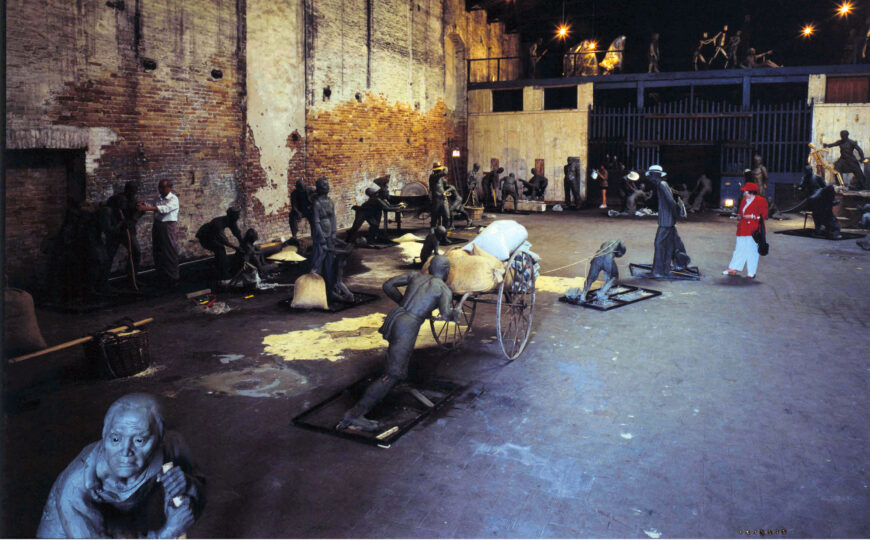

Cai Guo-Qiang, Venice’s Rent Collection Courtyard (installation view at 48th Venice Biennale), 1999, clay with wood and wire frames (photo: Elio Montanari) © Cai Guo-Qiang

Imagine entering the Venice Biennial (a biannual art exhibition) and coming face-to-face with a clay sculpture of a man whose arm has fallen off, or whose nose is crumbling from his face. You may wonder if this was a mistake. Did the artist forget to fire his sculpture in the kiln? Or did you wander into a studio filled with unfinished or discarded artwork? In actuality, this degradation was a key conceptual component of Cai Guo-Qiang’s Venice’s Rent Collection Courtyard, created for a section of the 1999 Venice Biennial designed to showcase the work of emerging artists. Cai’s work won the prestigious Golden Lion Award.

Wang Guanyi and students from the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, part 1: Bringing the Rent, from Rent Collection Courtyard (detail), 1965, 114 fired-clay figures (Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, Chongqing)

Recreating an earlier sculpture

Cai’s sculpture consisted of life-sized representations of peasants paying rent to a ruthless landlord. Rather than emerging from the artist’s imagination, the figures were recreations of the most famous socialist realist sculpture from the Chinese revolutionary period under Mao Zedong—Rent Collection Courtyard. The sculpture was created in 1965 by artist Wang Guanyi and students from the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute. It consists of 114 fired-clay figures and illustrates the exploitation of the peasantry by landlord Liu Wencai.

Wang Guanyi’s sculpture was effective political propaganda for the Communist Party of Mao Zedong, who took control of China in 1949, because it testified to the oppression of the peasantry by landlords, a feudal system, which Mao sought to overturn. The suffering of the peasants is apparent through such details as a young boy being whipped, a woman being separated from her baby, and an old man struggling to push his large bag of grain towards the landlord. Typical of Mao’s utilization of visual art as an educational tool, this sculpture was made as part of a political campaign titled “longing for the sweet through remembering the bitter,” meant to encourage the populace to be thankful for the blessings of their current communist reality by contemplating the horrors of the feudal past. From the Maoist perspective, under the old system, peasants were exploited and mistreated by the bourgeois class, while under communism, they were considered heroes within a system of class struggle. However, 42 years later, Cai Guo-Qiang’s Venice’s Rent Collection Courtyard was not a verbatim recreation of the original sculptural tableau. Rather, it contained important differences that opened possibilities for a new political critique.

Collective vs. artist

Under the leadership of Mao Zedong and the Communist Party in the 1960s, individual expression was suppressed in favor of collective authorship. In the realm of culture, this meant that many works of art, including Rent Collection Courtyard, were made collectively, with oversight by the three “heroes” of Mao’s revolution: soldiers, peasants, and farmers. In fact, the original tableau was purported to have been created under the supervision of the very peasants who were exploited by Liu (who by then lived in a nearby commune). As a work of socialist realism, the sculpture was meant to reflect ideal values of the socialist revolution.

Cai Guo-Qiang, Venice’s Rent Collection Courtyard (installation view at 48th Venice Biennale), 1999, clay with wood and wire frames (photo: Elio Montanari) © Cai Guo-Qiang

Venice’s Rent Collection Courtyard was similarly made collectively, though under the leadership of one of the most well-known contemporary Chinese artists of the early 21st century: Cai Guo-Qiang, who reports being moved when he saw the original as a child. In order to make the Venice version, Cai hired ten academically-trained artists, including one of the artists who made the original tableau, Long Xuli, as well as other well-known contemporary artists like Ai Weiwei, Chen Zhen, and Zhang Huan. Cai himself did not participate in creating the figures.

The work sparked controversy when the president of the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, Luo Zhongli, threatened to sue the Venice Biennial over copyright infringement. Though the suit was never brought, this situation raised important questions about how to retrospectively apply copyright laws to works made within a collective, communist society where private property had been abolished. It was also criticized by Long Xuli, who was angry when Cai did not share his award money with him and the other workers who created the original sculpture.

Audiences in China and abroad

In 1942, Mao Zedong, in a famous speech, clearly stated the purpose of art and literature under communism:

Many comrades like to talk about ‘a mass style.’ But what does it really mean? It means that the thoughts and feelings of our writers and artists should be fused with those of the masses of workers, peasants and soldiers. To achieve this fusion, they should conscientiously learn the language of the masses.Mao Zedong [1]

In keeping with this declaration, the original work was initially installed in the mansion of landlord Liu Wencai. The subject matter and location would have reminded the audience, “the masses of workers, peasants and soldiers,” of the abuse they had suffered under feudalism and how much better their lives had become under Mao Zedong’s socialism. A partial copy was made and exhibited in Beijing, where it was seen by half a million viewers. After this, in 1967, another plaster copy was sent to North Korea, Vietnam, Japan, Denmark, France, Albania, among other countries, in order to extol the virtues of Mao’s revolution on an international stage. Cai’s work, therefore, could be seen as one copy among many.

Cai Guo-Qiang, Venice’s Rent Collection Courtyard (installation view at 48th Venice Biennale), 1999, clay with wood and wire frames (photo: Elio Montanari) © Cai Guo-Qiang

Cai was invited to create his work at the 1999 Venice Biennial by curator Harald Szeemann, who had been fascinated with the original Rent Collection Courtyard for years. The exhibition bookended a decade of exhibitions that brought contemporary Chinese art to an international audience. Many Chinese artists and critics were frustrated that the most popular contemporary Chinese artworks accepted into the Western-dominated global art market included symbols of the Cultural Revolution that invited simplistic anti-communist interpretations. They argued that artists like Cai, who had lived outside of mainland China since 1986, used these symbols not as a way to authentically express lived reality in China, but to become famous by pandering to the outsiders’ expectations of China (which were still very much influenced by the propaganda of the Mao era). As an early example of Chinese art at the Venice Biennial (China didn’t yet have a national pavilion by this point), those still living in mainland China questioned the relevance of Szeemann’s choice of Cai’s artwork to represent the contemporary art of their nation. If the original Rent Collection Courtyard remains a symbol of the values of the Chinese Communist Party to this day, Cai’s disintegrating version casts doubts on its continued relevance in the context of a country that had embraced global capitalism and accepted the accompanying social stratification.

Rent Collection Courtyard, 1974, copper over fiberglass (Art Museum of Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, Chongqing)

Materiality and performance

In the 1960s and 70s, the original Rent Collection Courtyard was remade multiple times. The first version was made with wooden frameworks covered with straw, clay, clay mixed with cotton, and glass eyes. Other clay versions of the sculptures were subsequently fabricated in cities like Guangzhou, Shanghai, Wuhan, Xi’an, and Chongqing. However, in 1964, when it was decided that a version would travel outside of China, it was made of plaster since clay was too heavy and fragile to be moved repeatedly. In 1974, the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute created a copper-plated fiberglass version, which remains in the institution’s galleries to this day.

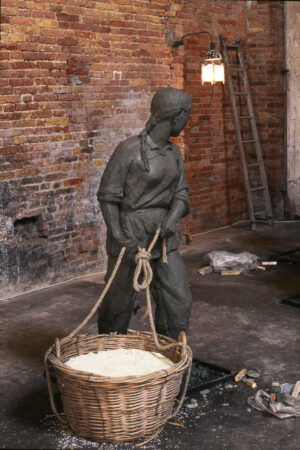

Long Xuli sculpting a clay figure (detail), Cai Guo-Qiang, Venice’s Rent Collection Courtyard, clay with wood and wire frames, 1999 (photo: Elio Montanari) © Cai Guo-Qiang

The artists creating Cai’s version used photographs of a 1967 plaster version as a reference for their figures. Additionally, pamphlets describing the creation of the original Rent Collection Courtyard were provided to the audience for context. The figures were made with wire frameworks and filled out with clay and glass eyes. Unlike any of the original versions, in Cai’s version, the clay was not fired. In fact, Cai’s version is closer to a performance artwork than a sculpture. Throughout the opening of the exhibition, Cai and his team of sculptors built the figures before the audience’s eyes. He has said that he wanted to move away from “looking at sculpture” to “looking at the making of sculpture.” [2] By the time the team of sculptors were working on one set of figures, another was already falling apart, inhibiting the viewer’s ability to see the entire tableau at once. Therefore, the focus of Cai’s work was about process over object: first, the act of making the sculptures; next, their disintegration.

Meanings

Within the context of the Venice Biennial, one of the world’s oldest and most renowned global art institutions, the disintegration of Cai’s sculptures adds new interpretive possibilities beyond the original sculpture’s socialist message. Being included in the Venice Biennial raises the status of an artist, and with it, the price of their artwork. The ephemeral nature of Cai’s work, however, meant that it could not be sold. The original Rent Collection Courtyard represented a certainty in the power of art to express a clear and sustained political message, no matter how many times it was copied or where it traveled. Cai’s iteration, however, introduced new negations: not just a negation of feudalism (as in the original) and socialism (a common interpretation), but also a negation of modernist assumptions that artworks are closed systems of meaning that do not change within new contexts, that global biennials are always at the service of the art market, and that global capitalism (as represented by the art market) is a sustainable economic model.