Mark Dion, Neukom Vivarium greenhouse, design approved 2004, completed 2006, mixed media, 80 feet long (structure) (photo: Another Believer, CC BY-SA 4.0)

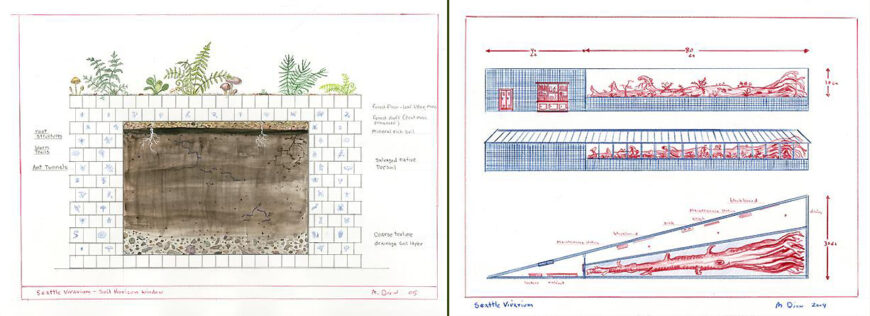

A greenhouse stands at the intersection of Elliott Avenue and Broad Street in Seattle’s Olympic Sculpture Park. An eighty-foot-long one-story shelter, it tapers toward the back, with glass walls and a sloping glass roof. A sixty-foot tree trunk lies inside on a waist-high bed of soil running the length of the building. The exterior walls of the bed are tiled, with a variety of flora and fauna illustrated on some of the tiles. Filtered sunlight enters through the green-tinted glass walls and roof. There is a mechanized watering system for the prostrate log and one that shades the glass surfaces. A cabinet displays the architectural plans for the shelter and learning tools related to its content, such as drawings, plans, and implements used in the project and information on the tree and the living organisms it hosts. Neukom Vivarium is an installation by Mark Dion from 2006.

Olympic Sculpture Park (photo: Seattle Department of Transporation, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Once an abandoned industrial site

The Olympic Sculpture Park sits on the slopes of a hill overlooking Seattle’s waterfront, adjacent to a gentrified residential and a commercial neighborhood close to the city’s downtown. The Seattle Art Museum (SAM) launched the project of turning the eight-and-a-half-acre abandoned industrial site from the 1970s into a free-admission sculpture park. Owen Richards Architects designed the park, which opened in 2007. Operated by SAM, the site currently exhibits twenty sculptures by fifteen artists, several of them internationally known, such as Louise Bourgeois, Alexander Calder, and Richard Serra. Dion is one of the youngest artists in this group.

Mark Dion (born 1961) is a conceptual artist who has been exploring cultural representations of nature and relationships between science and art. Though his attention to nature stems from his appreciation of American landscape painting of the Hudson River School, science has been central to his creative approach. For Dion, science explains how things are in the physical world, whereas art articulates human feelings about that world. While not hesitant to question the objective authority of science, his projects are frequently grounded in scientific research on pressing issues concerning human ties with the planet. His installations offer fictional spaces that are not only accessible to a regular audience but which also provide educational insights into the subjects of the work. To build a bridge between science and art, they often examine structures and systems fundamental to nature as well as those that sustain cultural institutions.

Structural critique

Dion’s work is aligned with the art of structural critique that emerged more than half a century ago in the European and American art scenes. Around the 1970s, many artists began examining social and cultural institutions, such as the museum. Since its development in Europe in the late 18th century, the museum—especially natural history museums but eventually art museums as well—had been regarded as a neutral cultural space. It was widely believed that the museum was unaffected by the politics or power relations that inform other institutions and that its sole agenda was delivering objective, secular knowledge through exhibitions of decontextualized objects. The German-born Hans Haacke, the Belgian Marcel Broodthaers, the American Michael Asher, and others creatively dismantled that myth. Through a wide range of interventions in the spatial and administrative structures of museums, their art convincingly demonstrated that museum exhibitions are indeed ideological representations of cultures; that far from their claim of universality, the knowledges such displays offer are historically constructed with specific agendas; and that various forms of power dynamics actively influence the operation of the institution. In other words, the museum itself became their subject. Such creative strategies are loosely known as institutional critique.

Before focusing exclusively on institutions, Hans Haacke was involved in rigorous investigations of systems of nature; various natural phenomena involving air and water were his subjects in the late 1960s. Mark Dion can be regarded as a second-generation artist in this lineage, along with the Americans Fred Wilson and Andrea Fraser. However, where Wilson, Fraser, and Haacke exclude nature in their institutional critique of recent decades, references to nature prominently coexist in most of Dion’s installations alongside critiques of social systems and orders. Neukom Vivarium is a notable instance where aspects of systems of nature are juxtaposed with the cultural systems of the display of nature.

Mark Dion, Neukom Vivarium greenhouse, design approved 2004, completed 2006, mixed media, 80 feet long (structure) © Mark Dion

An enormous Western Hemlock

Neukom Vivarium was specifically commissioned for the sculpture park. The Neukom family was among the chief donors that made the project possible, and a vivarium is a sanctuary with a semi-natural environment where animals are held for research. [1] On February 8, 1996, an enormous Western Hemlock fell in the protected watershed area outside Seattle. While lying in the forest, the dead tree gradually became a habitat of a range of living beings, from moss, lichen, and fungi to insects, mice, shrews, and birds. Such a fallen tree is known as a nurse log for its support of a nascent ecosystem. In 2006, after five years of research and planning, Dion had the log along with some of its inhabitants extracted from its natural setting and transported to the sculpture park, where it was carefully laid on the bed of soil, and cut to fit the bed. The shelter was then built around it. In the temperature-controlled interior, the intensity of sunlight filtering through the green-tinted glass walls and the roof approximates the spectrum of light seeping through the green canopy in the log’s previous home, the mechanically operated shades further regulate light, and the timed automated sprinklers periodically water the tree, simulating the water supply in the wilderness.

Dion believes the work brings the forgotten phenomenon of a natural cycle of life back into the city. And because the Western Hemlock—botanically known as Tsuga heterophylla—is the state tree of Washington, its presence at this site is especially meaningful. Not only is nature presented here as a process, but the entire installation unequivocally demonstrates the difficulty of replicating natural phenomena. The sharp architectural perspective of the shelter is meant to generate what Dion calls an “Alice-through-the-rabbit-hole” effect, where visitors enter a fictional space that challenges their perceptions and prejudices about nature, science, and art. Since the artist, however, is more interested in institutional ideas of nature than about nature itself, his strategy is to make his audience fully aware of the artifice of the cultural system that exposes the complexity and diversity of a natural one. [2]

The Neukom Vivarium, in fact, is a hybrid: it is a showroom, a laboratory, and a classroom. Magnifying glasses provided at the site allow visitors to minutely observe the nuances in the ecosystem nourished by the nurse log as well as changes evident on successive visits. Additionally, the images on the tiles drawn by local wildlife illustrators and the content of the cabinet offer educational insights into a cultural process that intervenes in nature. Unlike some of the other exhibits in the park that may demand prior knowledge of contemporary art, here visitors are invited to engage in a learning process via tools and resources displayed in the greenhouse that illuminate the central exhibit and the ecological microcosm it nurtures. In this way, the entire installation, including the nurse log, the architecture, and the learning material, make a profound connection with the content of the work possible. To ensure this connection, Dion adopts a variety of strategies borrowed from science, archeology and the legacy of institutional critique in art.

Digging the ground or scavenging the wilderness or the ocean for specimens or artifacts is often central to Dion’s methodology. The meticulous method of transporting the Western Hemlock from the wilderness to the sculpture park testifies to this practice. An artist with no professional background in archeology, he playfully labels himself a “cultural archeologist.” Dion is also fascinated by the Enlightenment tradition of scientifically classifying living organisms based on physical attributes or types, a procedure known as taxonomy, which he also uses to organize all his objects. His Classical Minds (Scala Naturae and Cosmic Cabinet) from 2017, for instance, has natural and cultural objects classified in a hierarchy.

Shelf of archival materials, Mark Dion, Neukom Vivarium, design approved 2004, completed 2006, mixed media, 80 feet long (structure) (photo: Dale Simonson, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Archiving nature

In Neukom Vivarium, Dion classifies both natural components (the tree itself) and cultural ones (information about the tree and the process of extraction) to offer his audience an avenue of discovery. Moreover, his interest in taxonomy logically leads to his engagement with archives. Artists such as Marcel Broodthaers and later Fred Wilson addressed the idea of the museum archive to unpack its conventional identity as a neutral storage of objective information and expose its artificiality as a historical construct. Likewise, this installation, as with many of Dion’s other projects, hinges on the meticulous classification, record-keeping, and storage of objects, creatures, and everything else on display, which demonstrates his playful experiments with the archive as a source of knowledge.

The artist is frequently drawn to the Wunderkammer, or cabinet of curiosities, to display the findings of his research-based pieces. During the European Renaissance, many wealthy men avidly collected disparate objects—both natural and handmade—and displayed them in cabinets based entirely on personal preferences. The arrangement of contents in the specially made interactive cabinet in Neukom Vivarium (like those in several of Dion’s other projects) is thoroughly logical, yet the Wunderkammer historically predates taxonomy and logical display of artifacts and specimens (an Enlightenment tradition grounded in Reason) by a couple of centuries. This ironic anachronism that delightfully brings together two histories—that of taxonomic display and the legacy of the idiosyncratic presentation of curiosity cabinets—indicates that, like the museum and the archive, not only is Dion’s cabinet an artificial apparatus, but so is the historic Wunderkammer.

New tree sprouting from log, Mark Dion, Neukom Vivarium greenhouse, design approved 2004, completed 2006, mixed media, 80 feet long (structure) (photo: bikingseattle, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Collaboration is fundamental to almost all of Dion’s projects. For Neukom Vivarium, he worked with soil scientists, biologists, architects, illustrators, and heavy transportation experts, not to mention the community volunteers who are the current custodians of the exhibit. He does not care whether the work is considered art per se; rather, his goal is to produce a learning experience, not just for his audience in contact with the finished product, but also for himself and the others involved in its making. It is in this spirit of collaboration that his attempt to connect science, art, nature, and culture is most strikingly evident.

Despite all the effort, however, the project is unsustainable in the long run. While the nurse log gradually decomposes, another of its kind might sprout from the mother log and eventually grow into an enormous tree that will be impossible to contain in the greenhouse. For Mark Dion, Neukom Vivarium represents an intervention in nature to build a failure—the futility of simulating nature. Rather than promising a better future, he feels his task is to hold a mirror to the present to demonstrate how natural systems, when destroyed, are impossible to simulate, regardless of commitments and resources. While this tree fell on its own, Dion’s goal (in addition to providing insights into the complexities of natural phenomena) is to make his audience ponder the consequences of such destruction when caused by human actions. While care of the nurse log seeks to teach visitors to be responsible with nature, the log awaits its final demise and, by extension, the conclusion of Dion’s project.