Kiki Smith, Lying with the Wolf, 2001, ink and pencil on paper, 223.5 x 185.4 cm (Centre Pompidou, Paris) © Kiki Smith

This delicate but large-scale work on paper, which depicts a female nude reclining intimately alongside a wolf, represents the assimilation of several themes that Kiki Smith has explored throughout her decades-long career. Featuring an act of bonding between human and animal, the piece speaks not only to Smith’s fascination with and reverence for the natural world, but also her noted interests in religious narratives and mythology, the history of figuration in Western art, and contemporary notions of feminine domesticity, spiritual yearning, and sexual identity.

Lying with the Wolf is one in a short series of works executed between 2000 and 2002 that illustrates women’s relationships with animals, drawing from representations found in visual, literary, and oral histories. Smith is most interested in narratives that speak to collectively shared mythologies: these include folk tales, biblical stories, and Victorian literature. Yet the once-familiar stories are then fragmented and conflated with one another to form new clusters of meaning and association.

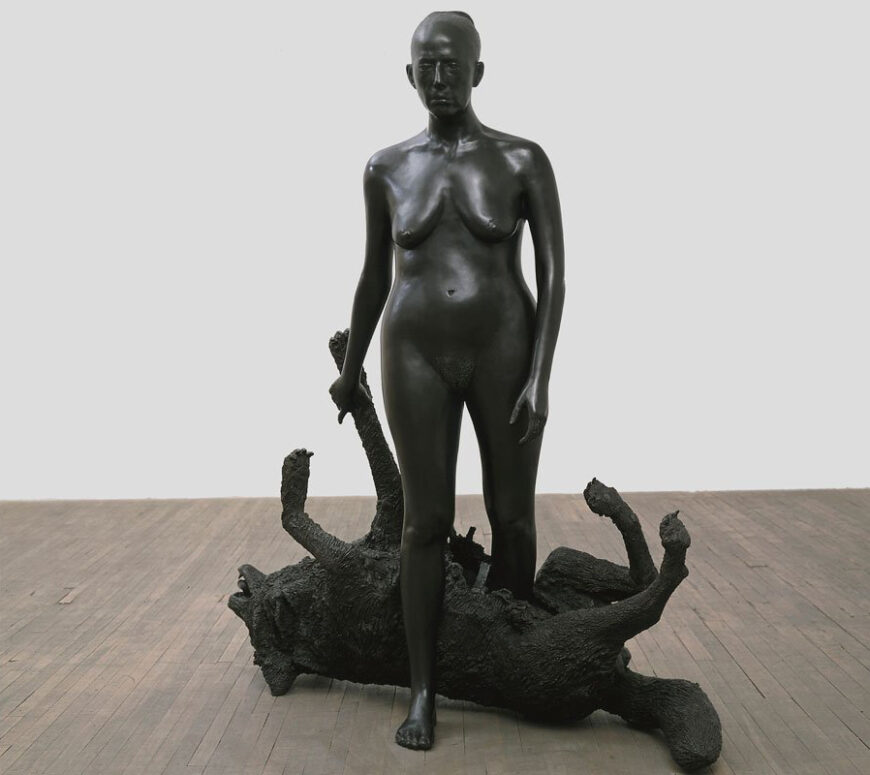

Kiki Smith, Geneviève and the May Wolf, 2000, bronze, 177 x 66 x 66 cm, 106 x 35 x 142 cm (Denver Art Museum) © Kiki Smith

Intimate relationships with nature

Many of Smith’s works from this period feature a female protagonist who is based on Little Red Riding Hood as well Sainte Geneviève, the patron saint of Paris. Geneviève is herself often associated with Saint Francis of Assisi because of her close relationships with animals and her ability, in particular, to domesticate wolves.

Other works in the series include Geneviève and the May Wolf—a bronze sculpture in which a standing female figure calmly embraces the wolf—and Rapture, which is perhaps more closely aligned to Little Red Riding Hood, as it depicts a woman stepping out from the stomach of the recumbent creature.

Woman embracing wolf (detail), Kiki Smith, Lying with the Wolf, 2001, ink and pencil on paper, 223.5 x 185.4 cm (Centre Pompidou, Paris) © Kiki Smith

The pair as depicted in Lying with the Wolf, however, seems locked in a more intimate embrace, as the wolf nuzzles affectionately into the nude woman’s arms. She wraps herself around the animal’s body in a gesture of comforting, her fingers stroking the soft fur beneath its ears and along the side of its stomach. The wolf’s wildness is tamed, and both figures seem to nurture one another, floating within the abstract space of the textured paper surface upon which they are delicately drawn. Smith imbues a story that is normally quite violent with a kind of tenderness that is characteristic of her overall aesthetic.

Feminist approaches to narrative

It has been suggested by some critics that Smith’s reinterpretations of Little Red Riding Hood and Sainte Geneviève represent a feminist approach to popular folktales. This is supported by her placement of “woman” amidst the natural world, but also, importantly, at a structural level: in the way in which the two narratives are fragmented and combined. Borrowing from divergent sources in order to forge a new storyline, Smith demonstrates the slippery relationship between a visual image and its multiple references, adopting a narrative style indebted to feminist re-writings of history.

As the curator Helaine Posner has explained: “Instead of presenting them in their traditional roles as predator and prey, Smith re-imagined these characters as companions, equals in purpose and scale.” [1] The distinction between “predator” and “prey” might be thought of as a metaphor for hierarchies of power in human relationships, which have traditionally been drawn along the lines of gender, race, and class. Because patriarchal societies typically grant more power to men, while requiring women to be submissive or dependent, we can think of this “overturning” in Smith’s art as a political statement against such inequalities. The artistic narratives portrayed in her work are ones in which binaries are flipped and opposing qualities are merged; in so doing, Smith asserts a critical feminist position that favors the articulation of multiple meanings.

“Walking around in a garden”

My career has stopped being linear. A couple of years ago, the story line or narrative fell apart… [2]

As is the case with Lying with the Wolf, several of Smith’s works integrate a diverse list of themes and motifs that she has accumulated over the course of her career. The artist continuously re-imagines tropes she has used in past works, with the result that her practice does not seem to progress through discrete artistic stages. Rather, she works in cycles and layers; she has described her career as an act of meandering, or “walking around in a garden.”

Kiki Smith grew up in a vibrant artistic family; she is the daughter of the sculptor Tony Smith and the opera singer Jane Lawrence Smith. She has spoken fondly of the Victorian house in which she was raised in South Orange, New Jersey, and how it captured her young imagination as a historical artifact with its own memories and indices to the past. The notion of “home” has been central to her practice, and she likens it to the human body, a theme that is pervasive across her oeuvre. Domesticity, fragility, and the humble materials of craft and folk arts feature strongly in her work.

Abjection and the body

While Kiki Smith’s early work is aligned with the collaborative and activist art scene of the 1980s, she became known for intimate explorations of the human body in the following decade, often through life-sized sculpture that honored the figural tradition in Western art.

Kiki Smith, Blood Pool, 1992, wax, gauze, and pigment, 106.7 x 61 x 40.6 cm (The Art Institute of Chicago) © Kiki Smith

These works emphasized the body’s vulnerability and made reference to feminist theories of the “abject,” which conceived of the body as a messy, porous, and boundary-less system. Blood Pool, for instance, features a small, apparently violated figure, huddled into a fetal position on the floor. Many other works of this period feature bodily fluids or marks of injury.

Mysticism and mythologies

Throughout the 1990s, Smith would come to embrace her religious upbringing, creating works that are spiritual, ethereal, and markedly more decorative. Celestial motifs and references to the natural world became ubiquitous, although these themes are still deeply connected to the body. As an investigation of the body in its capacity for fertility, reproduction, and nurturing, this turn towards the natural environment would eventually lead Smith to her interest in animals and our connections to them.

Lying with the Wolf is an extension of this yearning to connect the earthly with the spiritual and the personal with the collective.