Fountain (detail), Douglas Cardinal, Louis Weller with GBQC and Polshek Partners, National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC, 2004 (photo: Gryffindor)

Design and heritage

You are a member of one of the midwestern nations of Native Americans. Your ancestors had no permanent architecture because they were nomadic hunter-gatherers (see photo below). But now you live on a reservation in South Dakota, or near the Twin Cities in Minnesota. You and your relatives want to establish a cultural center, or a day care, or health clinic for your people.

Cass Lake Health Clinic (Indian Health Service), Leech Lake Reservation (Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe), Minnesota

Do you want it to look like the local museum or clinic (image left) built by the Federal or State government? Probably not, because in the post-modern era since about 1965, various groups have proclaimed their specific ethnic identity. Native Americans now reinforce cultural memory despite the near-eradication of their cultures by European-American governments and individual prejudice. This emphasis is now common among other minority and religious groups that have suffered under dominant cultures here and abroad.

Your native nation will seek an architect perhaps not of Native American ancestry; that will depend upon available talent and sensitivity to your culture, although increasing numbers of Native Americans have studied architecture. You will want the design to suggest something appropriate to your heritage.

Edward S. Curtis, Moving camp (detail), c. November 19, 1908, photographic print, Atsina on horses with travois behind them, tipis in background, Montana (Library of Congress)

Midwest

In the Midwest, the result might reflect local types of lodges, tipis, and ceremonial buildings of the past, but made of practical and accessible modern materials since an original tipi made of animal hides would be impermanent and lightweight. When the original hides no longer kept out the weather, they were easily replaced with new ones, but people today want durable materials and have time and funds for less frequent maintenance. The tipi has inspired versions in concrete, the Shakopee Mdewakanton Community Hall (1989) by Johnson, Sheldon, Sorensen, in glass, the Southern Ute Cultural Center (2011), by Jones & Jones* (see image below) and in rough stone with wood beams as in the Chief Gall Inn (1972) designed by Harrison Bagg at the Standing Rock Reservation in South Dakota.

The Four Winds School (1983) at Fort Totten on the Spirit Lake Reservation in North Dakota by Charles Archambault, Denby Deegan* and Neil McCaleb,* has the overall round shape of a ceremonial lodge or tipi but in order to accommodate classrooms, a gymnasium and cafeteria, the interior is divided into rooms around a circular core containing a tipi for counseling sessions.

Jones & Jones, Southern Ute Cultural Center, 2011 (photo: NorthShore Productions, Southern Ute Cultural Center and Museum)

Northwest coast

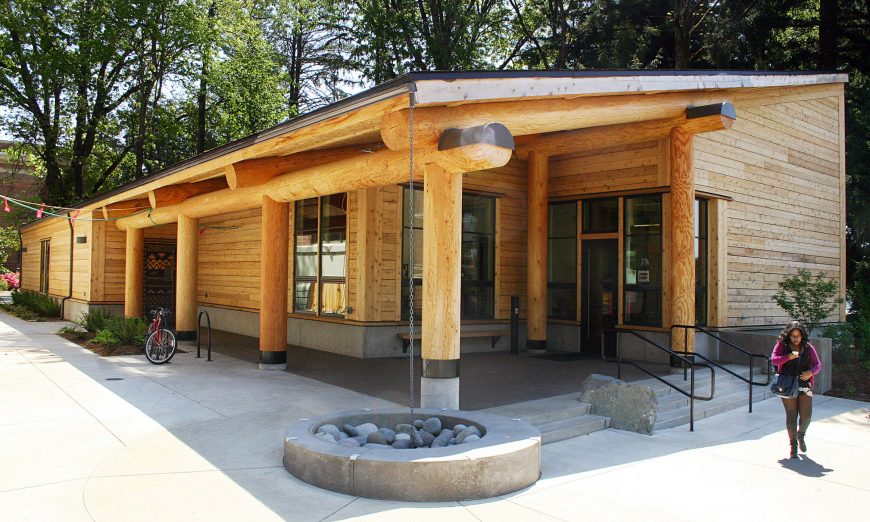

Along the Northwest coast, the building will probably be a rectangle of logs or milled wood with a pitched roof, evoking ancestral longhouses made from trees in the dense local forests. Retaining the traditional long shape while using some reinforced concrete for the sake of permanence, the Makah nation in Washington State created a cultural center in Neah Bay (1979 by Fred Bassetti architects) that has cedar cladding to harmonize with older buildings on the reservation. The Native American student center at Oregon State University uses logs and the longhouse form to accommodate members of several Native nations, without imitating buildings of one group (image below). The longhouse is a traditional form of architecture for several Native American nations in the coastal Northwest and was built to house extended families and community functions.

Jones & Jones*, Native American Longhouse (student center), 2013, Oregon State University (photo: Theresa Hogue, CC BY-SA 2.0)

At least one individual, Lawrence Joe,* of the Upper Skagit reservation in Washington has built a longhouse (1986) for therapeutic activities intended to accustom delinquent or disturbed youths to better ways of living according to traditional ethical standards. Northeastern forests, too, have provided logs for construction since ancient times, and various wood-covered buildings have been erected there for tribal offices, a student center at Cornell University (1991, by Flynn Battaglia, see detail below), museums and cultural centers. If there is insufficient money for a properly insulated wooden construction, a group may decorate a simpler building made of industrial materials with appropriate historically-based ornament, as in the Takopi Indian Health Center in Tacoma, WA (2002, by Mulvanny G2) or the Seneca-Iroquois National Museum in Salamanca NY (by Lloyd Barnwell,* designs by Carson Waterman*).

Haudenosaunee wampum belt design on exterior shingles (detail), Flynn & Battaglia, Akwe:kon (“all of us” in Mohawk), 1991, student residence and community center, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York

Southwest

In the southwest, a structure might be made of adobe (earthen brick structures made of sand, silt, clay, and straw), with thick walls and small windows to moderate heat during the warm months. Adobe requires frequent maintenance, however, so new buildings are often made of reinforced concrete, a durable material that can be colored to match the local earth of which adobe is composed. The San Felipe Pueblo school in New Mexico (image below) has geometric forms, close to those of an adobe building but with larger windows to admit more natural light and with subtle colors to enhance the appeal of the building to its young users.

Michael Doody supervised by Robert Montoya,* The San Felipe Pueblo School, 1982, San Felipe Pueblo, New Mexico (photo: courtesy of the author)

A southwestern building may also be built primarily of other natural materials, such as stone or wood, roughly hewn as the ancestors would have left it. The Pojoaque Pueblo Council Chambers, a seriously impressive building of modest size, is one example. A stone post barely altered from its natural state supports the sapling ceiling of the principal room in a thick-walled adobe structure. The building owes its form to two designers, the pueblo’s own governor, George Rivera* (also a sculptor) and Joel McHorse, Jr., as well as to its own construction organization—rather than to an imported designer. Along the highway entrance to the pueblo, Rivera* also designed a museum and cultural center using the solid, massive geometric forms customary in adobe building (see image below).

George Rivera with early assistance from Dennis Holloway, Poeh Cultural Center and Museum, 2012, Pojoaque (Po’su wae geh), New Mexico (photo: Howard Lifshitz, CC BY 2.0)

Urban centers

It is less easy to imagine an urban center where members of several native nations come together despite their varied cultural and architectural traditions. Whose culture will dominate? When it is impossible to find a site and funds for a new building, members must rent space in existing buildings that can be decorated inside with art or objects pertinent to the cultures in the area. The Minneapolis American Indian Center is a purpose-built center (see image below). The design connects the inside to nature through large glass windows. Woven wood designs by George Morrison* cover large parts of the outside. A ceremonial circle with stepped seating forms part of the entrance plaza. Inside, events take place below a ramp that replaces stairs or banked seating, to accommodate the customary ways of observing events—in small groups, spaced comfortably apart from one another. This building expresses Native life ways even though it does not imitate an indigenous building type.

Hodne-Stageberg Partners with Denby Deegan* and Dennis Sun Rhodes,* exterior wooden design at right by George Morrison,* Minneapolis American Indian Center, 1972 (photo: Bill Forbes, by permission, all rights reserved)

Natural forms

Several buildings for Native groups specifically evoke natural forms revered by the members of the nation. The Oneida in Wisconsin built a school with a plan in the form of a turtle (below left), and the same animal, sacred to the Iroquois confederacy, inspired the plan of a now-closed cultural center in Niagara Falls (below right).

Left: Aerial view, Richard Thern, Oneida Nation Elementary School, 1995, Oneida, Wisconsin (photo: ©Google). Right: Hodne-Stageberg with Dennis Sun Rhodes,* Iroquois Confederacy Cultural Center (closed), 1981, Niagara Falls, New York (photo: TC Fenstermaker, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

The National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., opened in 2004, is the result of collaboration, first with Douglas Cardinal* and GBQC, then with a consortium headed by Louis Weller* and Polshek Partners. Donna House,* an ethnobotanist and others also contributed to the result. Unlike smooth white buildings on the Mall, this one has a rough yellow stone surface, and is surrounded by landscaping of only indigenous ornamental or food-yielding plants. The boldly contoured facade confronts the neoclassical design of the Capitol. Inside and out, curving lines dominate because some Native American design participants claimed that these contours were natural and indigenous; they saw rigid straight lines as imports from abroad. A domed rotunda just inside the entrance accommodates ceremonies that can be viewed both at ground level and from surrounding balconies. As a building in the nation’s capital, the Museum reflects its position within the largely neoclassical context of the straight-sided Mall while accommodating various indigenous traditions.

Douglas Cardinal*, Louis Weller* with GBQC and Polshek Partners, National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC, 2004

The variety of native traditions, available materials, and architectural expertise has therefore given our continent new and culturally sensitive architectural forms during the last two generations.

*denotes Native American ancestry

Additional resources

Carol Herselle Krinsky, Contemporary Native American Architecture, New York, Oxford University Press, 1996