Painting Photography

The work of South African artist Marlene Dumas exists on a continuum between painting and photography. Simply put, she paints from photographic images. Or as she herself puts it: “I don’t paint people, I paint images.” Her sources range from the personal to the pornographic, from the medical to the political. Consisting of eerily rendered bodies and heads in thin washes of paint, ink or chalk, Dumas’s paintings approximate the genre of portraiture but her figures are stripped of any kind of individualizing features. Dumas’s portraits are, instead, rendered with a kind of dispassionate morbidity that is redolent of violence. A body or head in often sickly or garish colors and in broadly contoured outlines appears against a faint or blank backdrop. That her paintings seem bent on obliterating their photographic origins and reducing the figure to a lifeless prop, suggests that there is a profoundly social resonance to her work.

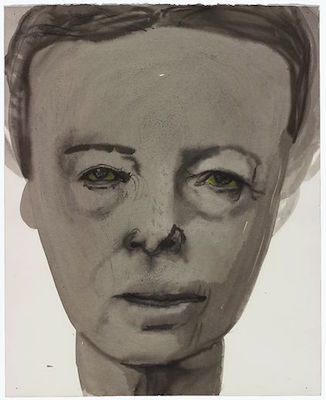

Single sheet from Marlene Dumas, Models, 1994, watercolor and ink wash on paper, 62 x 50 cm (Van Abbemuseum)

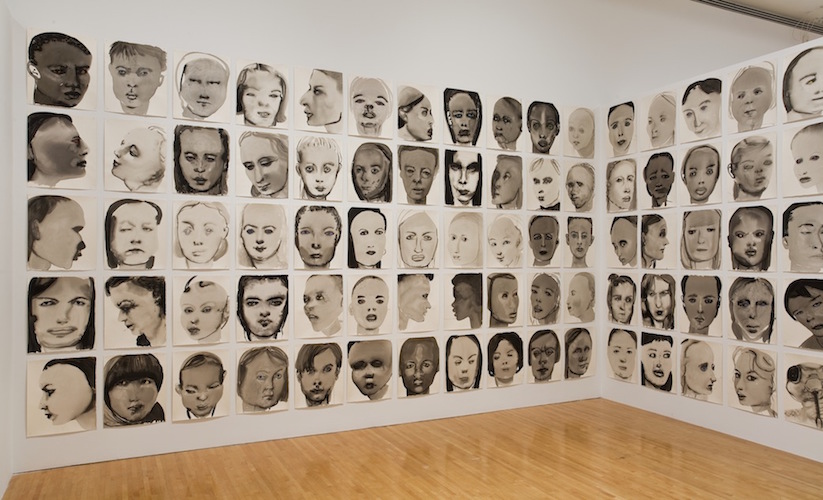

Models, 1994, is a case in point: it conjures up a catalogue of the dead and/or missing—an all too frequent reference point that underlines the global contemporary. Arranged in the form of a grid, Models presents 100 female faces as if they were the carefully laid out heads of a morgue. Positioned on blank surfaces and retaining only a minimum of individualized features, each “model” stares frontally or is rotated to profile or three-quarter pose. Faces vary from light skinned to dark and some have pastel colored eyes, but these are not the warms blues, greens and browns one might expect: lavender or lime-green instead serves to only heighten the disconcerting appearance of these disembodied figures. Who are these so-called “models?” As Dumas describes it: “There are pictures of the insane, pictures of fashion models, you have pictures of my friends…” In her description, as in her painting, Dumas gives them equal treatment: one becomes virtually indistinguishable from the other.

Against Beauty

To unravel the meaning of this work, we might start with the title. What are we to make of it? Surely it is ironic. “Model” has a number of meanings—prominent among them is the life model, a venerable tradition in studio art. But Dumas dispenses with this approach; her models are not sourced from life. They are taken from polaroids (the friends she mentions), book illustrations (the “insane”) and other sundry sources where clippings are readily available. The grim visages on display, casually acquired but so carefully reworked, suggest that Dumas is also not interested in idealized forms of beauty, as “model” might also suggest. Fashion models are the unobtainable standard of idealized female bodies in contemporary culture and have long been a site of intervention for feminist art. The term “model” in both popular culture and art history functions as an indicator of the “beautiful”—it means the female body perpetually displayed for the presumed male viewer.

One of the faces in Models is taken from an image of the feminist author Simone de Beauvoir and although it should not be taken as an overt symbol, it is clear that Dumas’s critical interrogation of the “beautiful” is part of a feminist lineage in art that includes, to take only but a few examples, the photo-documented performance Carving—A Traditional Sculpture (1971) by Eleanor Antin, the photo-text work of Lorna Simpson Twenty Questions (A Sampler) (1986), the self-portraits of Cindy Sherman or even the 1990s performances by Vanessa Beecroft where standing live models (actual models) were posed clad in heels with little else and faced an often awkward audience. But unlike her feminist counterparts who abandoned or rejected painting, Dumas compels us to consider the specific social force painting might have in contemporary culture. “I wanted to give more attention to what the painting does to the image, not only to what the image does to the painting” (as quoted in “Who is Marlene Dumas?” from Tate).

There is a deconstructive impulse in Dumas’s work: she de-eroticizes the pornographic imagery she appropriates; she de-personalizes portraits of friends; she turns the image of a celebrity icon like Naomi Campbell into something strange and unrecognizable. Even her portraits of children tack towards the monstrous.

Troubling and compelling

Comparisons are often made to the German painter Gerhard Richter (his notable series on the imprisoned Bader-Meinhof terrorist group for example) as well as to Dumas’s contemporary Lucs Tuyman whose faded paintings (indeed they look as if they are drained of color) seem to speak to a contemporary painting’s inability to fully invoke scenes of political life. But Dumas’s works provoke strong reactions. Is it because they speak so forcefully of violence done to persons? Persuasive arguments have been made that tie her work to the culture of apartheid she witnessed growing up as an Afrikaans-speaking Dutch descendant whose only access to the world was through print imagery (television did not come to South Africa until 1976). This certainly is a factor that underlines her work. But images of the dispossessed, the missing, and tortured are fairly routine fare in contemporary life.

Dumas’s troubling images are compelling not because of the haunting figures they construct but because of her transformation of once discrete categories of portraiture into something almost unrecognizable. For example, we expect “model” as a term to not stray too far from a conventional meaning, and as an image we expect the subject to hew to certain conventions. In the interplay between photography and painting that exists in Dumas’s work, the traditional function of portraiture is negated. It once served, in the history of oil painting, to commemorate the social status of an individual, to provide visual evidence of a marriage, or document the social bonds of family. In the nineteenth century photography usurped that job. The modern photographic portrait was supposed to capture something of the inner truth of the subject—one’s psychological being. The poetic reveries of Juliet Margaret Cameron or the individualized studio portraits of Felix Nadar became the standard bearer for a newly emergent bourgeois identity where self trumped community. Photography’s ability to capture likeness was soon harnessed by emerging ethnographic, psychological and jurisprudential discourses—criminals, and the insane all came under the powerful scientific gaze of the camera’s lens.

The artist and critic Allan Sekula once described, in an influential essay, two exemplary modes of photographic representation, regimes of visibility one might say that determined, rather than represented, identity. One is honorific: the respectable bourgeois portrait. The other is repressive: the cold mug shot of the criminal. In Dumas’s painted portraits the subject that emerges is at once both and neither of these. In an increasingly uncertain global culture, Dumas paints the indeterminacies and terrors of social identity.