“Which came first: the chicken or the egg?” is one of the most common household questions for school-aged children as they work to figure out the order of things. The Texas-based conceptual artist Celia Álvarez Muñoz uses the rhetorical question to open up a series of humorous photo and text montages that address bicultural language acquisition and photography as a marker of truth. One of her most iconic artworks, Which Came First? deftly introduces the viewer to Álvarez Muñoz’s recurring themes: childhood, language, religion, and gender.

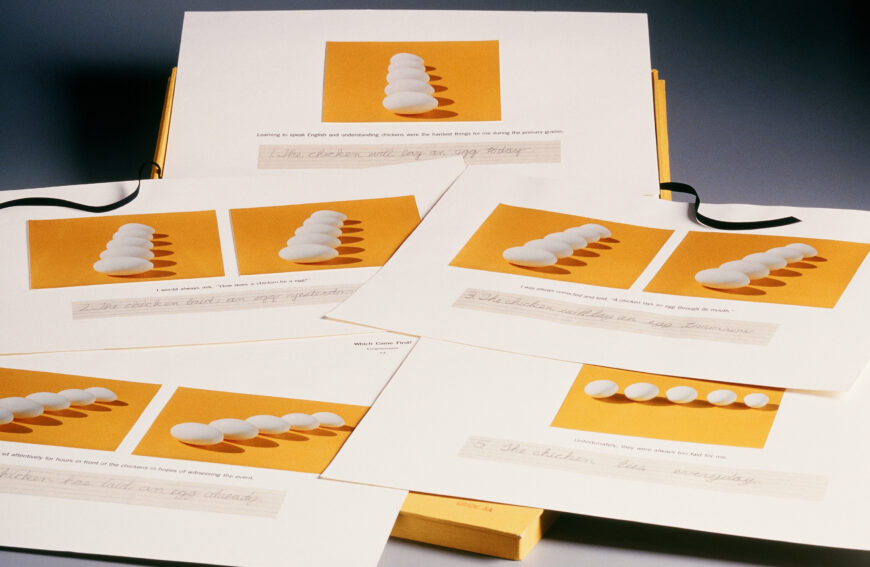

Celia Álvarez Muñoz, Which Came First? Enlightenment #4, 1982, chromogenic color prints and text, 31.6 x 47.9 cm (Art Institute of Chicago) © Celia Álvarez Muñoz, images cannot be reproduced without permission, photo: Tracy Hicks

Which Came First? Enlightenment #4 is a yellow cloth folio (book) containing five pages of narrative storytelling through photographs, letterpress, and handwritten calligraphy on Gekkeikan homespun paper. When displayed in museums, the work is usually shown framed in a horizontal, vertical or cruciform shape. The viewer is drawn to the warm, yolk-like photographs and the sequential series of varying perspectives of five eggs which cast shadows whether viewed from above, the side, or directly in front of the camera. The textual elements likewise draw the spectator in. The small type of the letterpress requires one to view it up close and the immediacy and tactile quality of a child’s handwriting inspires curiosity.

Innocent confusion

The first sentence of the artist book: “Learning to speak English and understanding chickens were the hardest things for me during the primary grades,” tugs at the viewer’s heart strings through a sentimental and confessional tone. The aged lined paper with a child’s handwriting (that of her son, Andy Muñoz III) performs as evidence of the memory she conjures. Throughout the sequence, we learn of the innocent confusion between the verbs lay and lie, and how this leads the child version of Álvarez Muñoz to believe that chickens lie everyday (instead of laying eggs). However, the power of the narrative driven by the text as both omniscient narrator and child also asks the viewer to consider: how does the camera lie? After all, depending on the angle of the photo, the camera can also be an instrument of deception.

Álvarez Muñoz began her artistic career in the commercial world of advertising as a fashion illustrator. Her exposure to the glitz and glamor of the industry sparked a critical attitude toward consumerism, especially the ways in which viewers consume images. When Álvarez Muñoz returned to school for her Master of Fine Arts, the methods of conceptual art—an art that is primarily focused on ideas rather than the appearance, beauty, or masterful execution of a work—offered her a familiar language in which to probe piercing social questions. There are many artists who work within this genealogy, juxtaposing image and text such as John Baldessari, Barbara Kruger, Adrian Piper, and Ed Ruscha, whose work she is in conversation with. In the first decade of her professional practice, the artist book became her preferred format for this experimentation.

![Celia Álvarez Muñoz, “Chispas Quemenme!” [“Sparks, Burn Me!”] Enlightenment #1, 1980 © Celia Álvarez Muñoz, images cannot be reproduced without permission, photo: Tracy Hicks](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/1_-copy-300x196.jpg)

Celia Álvarez Muñoz, “Chispas Quemenme!” [“Sparks, Burn Me!”] Enlightenment #1, 1980 © Celia Álvarez Muñoz, images cannot be reproduced without permission, photo: Tracy Hicks

The artist book

Artist books are interactive and sequential works of art that take their inspiration from the idea of a book but are often produced by artists as a one-of-a-kind object or a limited edition. Álvarez Muñoz’s fascination with books began early in her life. Her father served in World War II and among the items he brought back was a Nazi propaganda booklet, published by the People’s Commissariat of Enlightenment, to elicit support for their cause. Álvarez Muñoz was fascinated by how photos and text could be used to instruct, indoctrinate, and sell a particular point of view. As a tongue-in-cheek gesture, she adopted the name Enlightenment series for her artist books with the hope that they could be used in an opposite manner: to create doubt and to question power structures and reckless consumption.

Books became a way for the artist to structure projects that are based on childhood memories through a medium that allowed sequencing and pagination, stretching the possibilities of time and narrative storytelling. Her fondness for books may also relate to the years she spent as a school teacher in El Paso.

Texas borderlands and Chicana feminism

As an artist born and raised in El Paso, and its twin metroplex of Ciudad Juarez on the Mexican side of the border, Álvarez Muñoz has always negotiated a bicultural and bilingual heritage. Much of her work reflects this borderland subjectivity and a hyperawareness of linguistic code-switching, pronunciation, and mistranslation. Her childhood misunderstanding of “to lay” and “to lie” speaks to these experiences without it being sad or traumatic. She revels in the humor which attracts a wide audience.

Celia Álvarez Muñoz, Ave Maria Purisima! Enlightenment #8, 1983, ash wood box, 7 frames, mixed media, 38.1 x 27.3 cm © Celia Álvarez Muñoz, images cannot be reproduced without permission, photo: Tracy Hicks

Her experience in the Texas borderlands also makes visible the Catholic beliefs and iconography that permeated her domestic life. From the images of saints she recalled her grandmother collecting in “Chispas Quemenme!” [“Sparks, Burn Me!”] Enlightenment #1 to the use of key phrases such as “Ave Maria Purisima” to indicate shock, disapproval, and unholiness as in Enlightenment #8, Álvarez Muñoz both honors and pokes fun at what is taught as good and bad in religious education.

Relatedly, Which Came First? also speaks to issues of gender and sexuality through a Chicana feminist lens. As the story narrates, she was told, “A chicken lays an egg through its mouth.” This white lie by an adult figure speaks to a kind of sexual repression influenced by Catholic education, given that chickens lay eggs through their rears, specifically through the cloaca. The fact that only female chickens (hens) can lay eggs also engenders a critical attitude towards the invisibility and devaluing of reproductive labor, the work women do to care for children and maintain daily life in their households. These concerns, which are not overt, but deduced by reasoning from the viewer, provide a glimpse of the consciousness raising efforts by Chicana women to work toward equity and greater freedoms.

This essay is part of Smarthistory’s Latinx Futures project and was made possible thanks to support from the Terra Foundation for American Art.