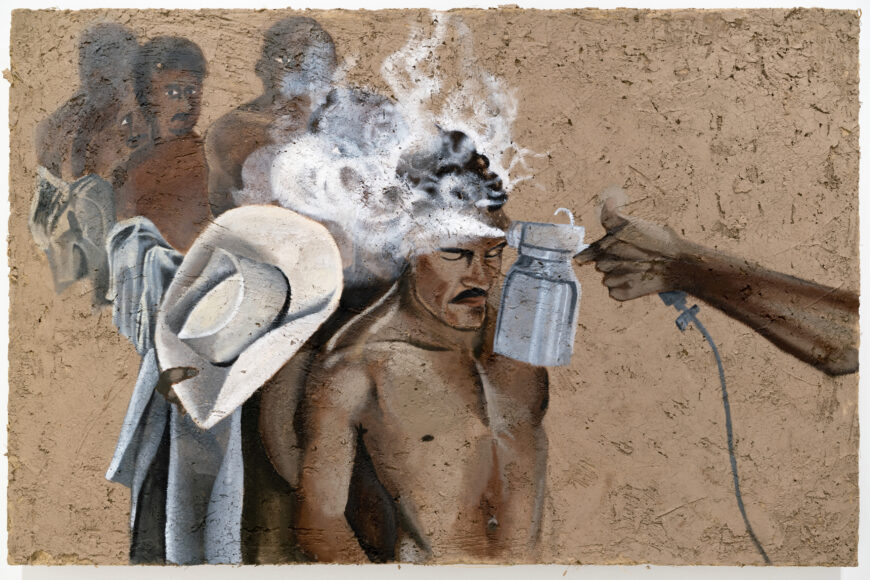

rafa esparza, Border Wash—after Leonard Nadel, 1956, 2019, adobe and paint (photo: Kaelan Burkett, courtesy of MASS MoCA) © rafa esparza

In Border Wash—after Leonard Nadel, 1956 (2019), a painting by Los Angeles-based artist rafa esparza, six or seven men, possibly more, stand close to one another in a line. They are stripped down to their waists, maybe fully. The men’s skin tones are on the same spectrum of brown as their indistinct but textured background. And with no ground or horizon line articulated, their appearance is almost ephemeral. One body flows into another, conjured by esparza but ready to drift away at any moment. Their flesh echoes the white vapor emanating from a compressed air sprayer, held by an outstretched arm, though the rest of this figure’s body remains outside the painting’s frame.

The men hold their shirts in their hands. One hand clutches a cowboy hat, clearly rendered and almost out of scale, an improvised sign of modesty as much as the mustaches of several of the men are a conventional sign of masculinity. The man in the foreground is the most concretely realized, the vapor curls around his thick hair and chiseled cheekbones. His eyes closed, a viewer may feel they can appreciate his muscled form, noting the way his trapezius and jawline are highlighted in white. His seemingly serene expression contrasts with the gazes of his companions, which pierce the vapor, with at least one looking out at the viewer.

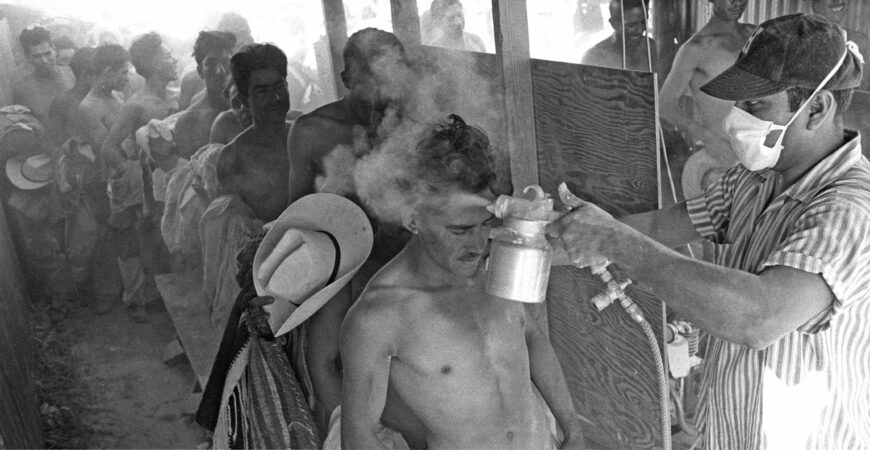

esparza composed a scene that places the viewer up close to the hazy action and mingles intimacy—even eroticism—with unease and vulnerability. What is in the canister? Who is spraying this vapor and why? The painting’s composition and title gestures to another relation: Border Wash is based on a photograph by Leonard Nadel that documented migrant laborers sprayed with a toxic insecticide by U.S. Department of Agriculture staff as they crossed the Mexico-U.S. border in 1956. The denigrating procedure was part of a “guest worker” agreement between the two countries, known as the Bracero Program. esparza’s gritty yet sensual approach proposes that memory of this state-sponsored abuse does not fade.

Leonard Nadel, A masked worker fumigates a bracero with DDT at the Hidalgo Processing Center, Texas, while others wait in line, 1956, gelatin silver print (National Museum of American History, Archives Center, Washington, D.C.)

Adobe

esparza painted this work on adobe, which he makes by hand out of dirt, hay, horse dung, and water, among other things. By choosing adobe as the support for Border Wash, he taps into the material’s complex history and cultural signification. Adobe is closely tied to the land on which it is prepared, taking on the color of the local soil and the shape preferred by its makers. The texture of the surface records the hands and handheld tools that shaped it. Indigenous people throughout what is today the Southwest U.S. have used adobe as a building block for centuries, making it one of the earliest and longest-standing construction materials in the Americas.

Adobe is a material close to esparza’s personal history too. esparza’s father, Ramón, worked in construction for decades in Mexico and the U.S. Ramón used adobe bricks to build his first home and made and sold bricks over the course of his career. He passed this expertise onto his son. For the most part, esparza makes adobe for his art with the help of family and friends. He consciously expands the scope of adobe’s intergenerational transfer of knowledge, which is normally patrilineal. In addition to making lighter work of a laborious process, he recognizes the way shared labor creates and maintains communities.

rafa esparza, Staring at the Sun installation view, 2019 (photo: Kaelan Burkett, courtesy of MASS MoCA) © rafa esparza

As a self-identified brown and queer child of immigrants, esparza is acutely aware of the ways homophobia, transphobia, and racism have interfered with people feeling at ease in spaces where cis masculinity and heterosexuality are policed, and how this unease intersects with race and class. This includes construction sites and the art world, spaces his adobe practice consciously bridges. esparza has spoken about an emotional distancing between himself and Ramón after he came out as queer in 2005, and how asking his father years later to teach him how to make adobe was a way to reset their relationship. For the artist, adobe-making has taken on the significance as a way to foster closeness to others (and to the land) for those who feel like “outsiders,” whether as a function of queerness or migration. As scholars of the history of gender and sexuality in the Mexico-U.S. borderlands have argued, both queerness and migration lead to shifts in physical and cultural proximities and arrangements that can arouse senses of loss and longing. These desires emerged in places like the Bracero Program processing camp, which was also a space away from familial and social surveillance, where migrants could experiment with new expressions of desire.

Braceros

By citing Nadel’s photograph, esparza also taps into a desire to remake the dehumanized image of the braceros, a word from Spanish that denotes manual labor. Nadel documented the poisonous fumigation of braceros in Hidalgo, Texas (near Reynosa, Tamaulipas), though it was repeated at camps all along the Mexico-U.S. border. The Bracero Program was a series of agreements between the U.S. and Mexican governments that established the legal and economic framework for the importation of Mexican laborers to the U.S., mostly for agriculture and railroad work, to address the labor shortage caused by World War II conscription. Over 4.5 million contracts were executed during the program, which ran from 1942 to 1964. While the braceros brought great productivity to their jobs, their health and welfare was often ignored.

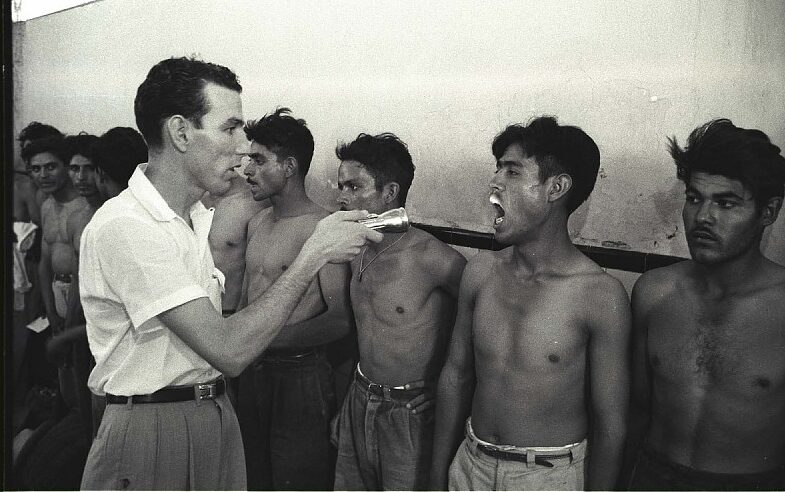

Leonard Nadel, Physical Examination of Braceros, 1956, gelatin silver print (National Museum of American History, Washington, D.C.)

Upon arrival at the camps, braceros were subject to humiliating physical exams and were sprayed on their heads and genitals with DDT, or dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane. This synthetic chemical was developed during WWII to kill insect-borne diseases such as typhus and malaria. The fumigation was an echo of immigration policy from earlier in the 20th century that required migrants from Mexico to bathe in gasoline to “delouse” themselves, and a reminder that migrants were persistently perceived by officials as dirty and ridden with disease. DDT was banned as toxic to humans and the environment in 1972. Though the braceros remained nameless, Nadel’s photos, which were reproduced in illustrated magazines at the time, made this dehumanization visible and contributed to the process of recognizing them as workers worthy of dignity and respect. esparza’s interpretation arguably pushes this humanization further. Without diminishing the abuse enacted on these men, he invites the viewer not to assume the men’s stoicism, or to ignore our own compassion when encountering this scene.

Vulnerability

Adobe construction is widely recognized for its strength and durability. This is part of the material’s appeal to esparza, the way it stands as evidence of intergenerational labor and an environmentally conscious relationship to the land. At the same time, the way esparza deploys adobe in Border Wash, as a slab with unfinished or unframed edges that are vulnerable to decomposition, suggests that he sees power in its vulnerability and precarity, just as he sees the same in the braceros he represents.

rafa esparza, Staring at the Sun installation view, 2019 (photo: Kaelan Burkett, courtesy of MASS MoCA) © rafa esparza

Border Wash was included in a solo exhibition of esparza’s work at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, known as MASS MoCA, in 2018. esparza laid adobe bricks on the floor. He also built two small votive-like vessels out of stepped bricks and filled them with soil. In one, an onion sprouted, reminding visitors that this material possessed the potential to generate a living organism. Adobe slabs, some painted with portraits and others unmarked, were hung on the walls.

Visitors were invited to walk over the bricks and they, along with the slabs, inevitably chipped and crumbled. Adobe is material at odds with the preservation aims of a modern museum, which demands various types of control: cleanliness, temperature, security, and so forth. Such institutions perceive non-standard art-making materials as potential contaminants. esparza has been asked by other museums to fumigate (and even radiate) his adobe, an uncanny echo of the processing of braceros. While MASS MoCA did not make this demand, it is an institution closely associated with minimalist art by mostly Anglo artists that is largely the product of (or visually references) industrial fabrication. In a 2017 interview, he asserted, “Adobe bricks are loaded; they signify brownness, the land, and labor … By building with adobe in galleries I am bringing all of this—and the muddy history of American soil, colonization, and progress—into a traditionally white context.”

Browning the white cube

For esparza, this “contamination” is the point. esparza has expressed an artistic and political interest in “browning the white cube.” With “white cube” he refers to the conventional aesthetic of contemporary museum and commercial gallery spaces, an almost universally modernist interior architecture: boxy, stark, and white. esparza also refers to the ways these spaces have historically excluded artists, curators, and audiences from racialized and other marginalized communities.

Notably, esparza’s work and the exhibition were developed during the 2016–20 presidential administration of Donald Trump, a time when dehumanizing anti-immigrant and transphobic rhetoric and policy were ascendant in U.S. political discourse. Trump staked his campaign in large part on the illusion of building a permanent and impenetrable wall between the U.S. and Mexico. The history of colonization in the Southwest, which resulted in the dispossession of Indigenous and Mexican people from these lands by largely Anglo settlers in the 19th century, was justified by “manifest destiny.” Adobe testifies to the longtime presence of Indigenous people as well as the history and present-day memory of colonial violence. From this point of view, an inert but organic and strong yet vulnerable material like adobe can be perceived to manifest the lives of “brown” people past and present. Border Wash proposes a textured sense of bonding and belonging.

Additional resources

Leonard Nadel Photographs and Scrapbooks, Smithsonian Institution

Leonard Nadel Photographs, Getty Research Institute

“Staring at the Sun: rafa esparza” at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, 2019

Deborah Cohen, Braceros: Migrant Citizens and Transnational Subjects in the Postwar United States and Mexico (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011).

Nicole Giudotti-Hernández, Archiving Mexican Masculinities in Diaspora (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021).

Greg Grandin, The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2020).

Laura G. Gutiérrez, “‘Cruising Utopia’ with rafa esparza’s Corpo RanfLA: Terra Cruiser (2022),” Intervenxions (February 17, 2023).

Laura G. Gutiérrez. “Time Dislocated: Masculinity and the Performance of Breathing,” Periscope (November 8, 2019).

Mireya Loza, Defiant Braceros: How Migrant Workers Fought for Racial, Sexual and Political Freedom (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016).

Carolina Miranda, “Two Artists from L.A. and Tijuana: Two Visions of the Border,” Los Angeles Times (29 November 2019).

Alexann Susholtz, “The Brown Project: Disruption as a Form of Agency in rafa esparza’s Adobe Works” (M.A. thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 2022).

This essay is part of Smarthistory’s Latinx Futures project and was made possible thanks to support from the Terra Foundation for American Art.