Marc Quinn, Self, 1991, blood (artist’s), stainless steel, Perspex and refrigeration equipment, 208 x 63 x 63 cm (originally collection of Charles Saatchi, now collection of Steve Cohen, New York)

The shock of the new

Shock value has been an important aspect of art since the nineteenth century. But is provocation always merely a case of superficial attention-grabbing, or can it ever have depth? Marc Quinn’s Self, a sculpture depicting the artist’s head made from his own frozen blood, is a perfect artwork for mulling over such questions. Shock is the probably the foremost element in its success and lasting impact on viewers: once seen, Self is not easily forgotten. The sight of blood often has this effect. For some it is an extremely distressing spectacle in its own right, and even for those of us used to transgressive artistic acts, the public display of real bodily fluids still retains its sense of taboo. But once the shock wears off, what are we left with? Does its meaningfulness erode over time, like a joke whose amusement diminishes on each rehearing?

Process and meaning

Making Self (1991): collecting blood

It is probably wise to first acknowledge the extraordinary amount of preparation and the lengthy ordeal Quinn put himself through to create Self. First, he took blood from his body – as you would do during a blood donation – over five separate sessions to stockpile a total of ten pints (5.7 liters). He then made a cast of his head by covering it with an all-over mask of plaster of Paris (leaving breathing holes for his nose). This perfect impression of the artist’s facial features was then removed, filled with the blood and frozen. When it was solid, the blood head was mounted within a Perspex box filled with silicone oil at a subzero temperature.

Making Self (1991): making the cast

This careful, quasi-medical process indicates the seriousness and meticulous planning that lie behind Quinn’s shock tactics. Ten pints is the average amount of blood in a human body, so among the other effects of Self is to make the spectator aware of the modest volume of this vital substance required to sustain a life. The freezing process is also one that might trigger thoughts of other modern medical practises such as cryopreservation (the technique of storing biological samples — and sometimes whole bodies — by keeping them at low temperatures for future regeneration). Quinn’s sculpture is, among other things, a life support system. It therefore suggests wider issues of life and healthcare in the modern world: Self is as dependent on science as our own lives are, and it leaves us space to contemplate the magical promises of medical technology, as well as its limits.

Marc Quinn, Self, 1991, blood (artist’s), stainless steel, Perspex and refrigeration equipment, 208 x 63 x 63 cm (originally collection of Charles Saatchi, now collection of Steve Cohen, New York)

Quinn’s education as a student of History and History of Art at the University of Cambridge can be seen as a vital component of his work as a whole, and here his engagement appears to be with ancient tomb sculptures. Much of what we study as art from early civilizations (such as from Egypt and China) is from burial chambers, where the intention was to preserve bodies and spiritually conquer death. Also, one of the chief purposes of all portraits has been to conserve an individual’s legacy. Quinn’s engagement with cryopreservation in a gallery setting reminds us of art’s ancient role in ensuring posterity.

Blood simple

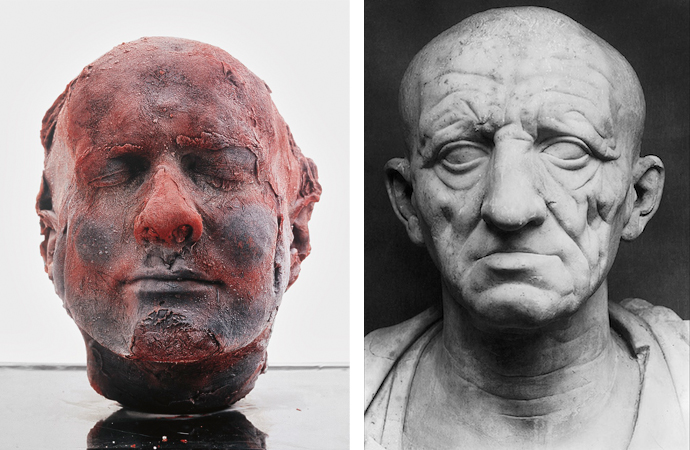

Left: Marc Quinn, Self, 1991, blood (artist’s), stainless steel, Perspex and refrigeration equipment, 208 x 63 x 63 cm (originally collection of Charles Saatchi, now collection of Steve Cohen, New York); Right: Head of a Roman Patrician from Otricoli, c. 75-50 BCE, marble (Palazzo Torlonia, Rome)

Disregarding the startling choice of sculptural material, there is little in the appearance of Self to cause alarm. In some respects, its presentation is rather archaic. It is a portrait bust, a format which originates in Europe with the Romans, and it sits on a plinth behind a glass case, much like an exhibit in a museum of antiquities. The head is subtly upturned with its lips pursed and eyes closed, giving it a sense of peacefulness and serenity — as if asleep or gracefully deceased. The casting process that Quinn used has picked up many tender textures from the surface of Quinn’s face such as the eye lashes, creases on lips and the folds of flesh on the ears. A sense of the macabre is thus conveyed only through its bruised, red and blue coloration, and arguably also the surface texture which bears marks left behind from the mold used in the process of casting and makes the head look scarred or decayed. Casting is a very old sculpting technique, but it looks as though Quinn is making reference specifically to the tradition of death masks, which were used by the Romans to record the physiognomy of deceased family members.

A literal portrait

Unlike more traditional materials of western sculpture such as marble, blood is not durable and will decay if not frozen. Similarly, the process of casting is traditional, but usually it is done with bronze or other precious metals, and not a bodily fluid. Value therefore becomes a significant theme, as blood — unlike marble and bronze — lacks monetary worth and yet is essential to life. The use of bodily fluids increases the sculpture’s status as a ‘true’ self-portrait in which the artwork serves not only to depict the artist but is also composed of a part of the artist’s own body, his DNA. As mentioned before, the presence of a refrigeration unit underscores the sculpture’s dependence on a source of power, arguably increasing its sense of vulnerability. Quinn has commented on the autobiographical dimension of Self saying that it reflects his alcoholism, as it is entirely dependent on electricity, just as he was reliant on alcohol. This self-expressive aim is also attested by Quinn’s aim to pay homage to Rembrandt, who repeatedly created self-portraits in the latter stages of his career, by making a new 10-pint blood Self every 5 years.

Sacrifice

Historically, blood is associated with sacrifice and ritual, such as in the Aztec Empire and Mithraism (an ancient Roman mystery religion centered on the god Mithras), and in some religions had been applied to sculptures in order to “animate” them. In Christianity the blood of Christ is also sacred and celebrated at the Eucharist. In other contexts, blood is symbolic of truth and family lineage — one speaks of a “bloodline” and agreements have sometimes been sealed by mingling blood. Quinn’s self-portrait can be identified in the crossroads of these various associations, indicating the potent, generative powers of blood, the veracity and individuality of the artist’s personal identity, as well as his self-sacrifice in the name of art.

The trope of the artist as a suffering, outcast martyr has been with us since at least the Romantic period. And it is not unrelated to the trope that this essay began with: that of the artist as provocateur, intent on shock tactics to turn heads. According to this stereotype, artists should behave like outsiders who position themselves beyond society, only in order to castigate and shock it with their piercing commentary. This tradition was given its most forceful early voice with Manet and his provocative works of the 1860s with such works as Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe. In the fierce competition of the art world every young artist needs to court notoriety if they want to be noticed — quiet conservatism seldom makes for front-page news. Causing shock is relatively easy, but the outrage quick wears off if the work lacks dimension, and there will be many forgotten names in the history of twentieth-century art, music and cinema who resorted to the kind of superficial shock whose impact petered out all too quickly.

Édouard Manet, Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the Grass), oil on canvas, 1863 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris)

Does Self fall into this category? A defense of its merits would point to the breadth of themes addressed in this essay: its painstaking process, its appropriation of medical technology, its art-historical reference points and its aim to act as a vehicle of the artist’s self-expression. Self, such an argument would run, serves as an example of provocation with a purpose, where medium, technique and message coalesce, and the art achieves both a memorable aesthetic and a satisfying quantity of conceptual ballast.