Christian Boltanski, Personnes, 2010, Grand Palais, Paris, Monumenta 3 (photo: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, CC BY 2.0) © estate of the artist

It is January 2010. As I enter the Grand Palais in Paris, the historic building’s interior is hidden from view by a high wall constructed of rusted biscuit tins, each with a four-digit number displayed on its front. Once I walk around the wall, a curious scene unfolds in the massive hall beyond.

Christian Boltanski, Personnes, 2010, Grand Palais, Paris, Monumenta 3 (photo: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, CC BY 2.0) © estate of the artist

Rows of rectangular spaces are neatly arranged in a grid with aisles in between. Marked by four poles at the corners and lit by a suspended light above, each space is piled with clothes—garments of various designs and colors. A mound of clothes more than thirty feet tall looms at the far end of the grid.

Christian Boltanski, Personnes, 2010, Grand Palais, Paris, Monumenta 3 (photo: Giovanni Sighele, CC BY 2.0) © estate of the artist

The mechanical claw of an enormous crane hovering above periodically picks up a few items from the mound, only to drop them back after raising the catch high in the air. Without any heat, the hall is cold and dreary. A strange, muffled boom, the sound of a beating heart, adds to the visitor’s discomfort, its repetitive rhythm overlapping the occasional metallic noise of the grasping crane. In an adjacent room, visitors are offered an opportunity to have their heartbeats recorded and transferred onto a compact disc. This is the French artist Christian Boltanski’s ambitious installation, Personnes, at the third edition of the exhibition, Monumenta.

Grand Palais, Paris, France (photo: Ștefan Jurcă, CC BY 2.0)

Coming of age after the Second World War

Christian Boltanski who died in 2021 remains one of the leading figures in conceptual art. His consistent pursuit of disturbing yet profound existential questions presented in a variety of installations has captivated his audience for more than five decades. Fascinated by the universality of death and the fragility of human existence, Boltanski was preoccupied throughout his career with notions of memory, loss, identity, and biography. Though he usually identified as a painter, he worked with a wide range of objects, materials, and modes of representation. The subjects and ideas fundamental to his projects—including Personnes—have their roots in his family and his coming of age in the years following the Second World War.

Boltanski was born in 1944 to a Corsican-Catholic mother and a Ukrainian-Jewish father a few days after the liberation of Paris from Nazi occupation. His father, a doctor, had to hide under the floorboards of their house for a year-and-a-half to avoid detection by the Nazi authorities. The family remained traumatized for years after the war, affecting Boltanski’s childhood. The Jewish Holocaust was a recurring theme in family discussions and his parents’ fears about losing their children put severe restrictions on him and his siblings.

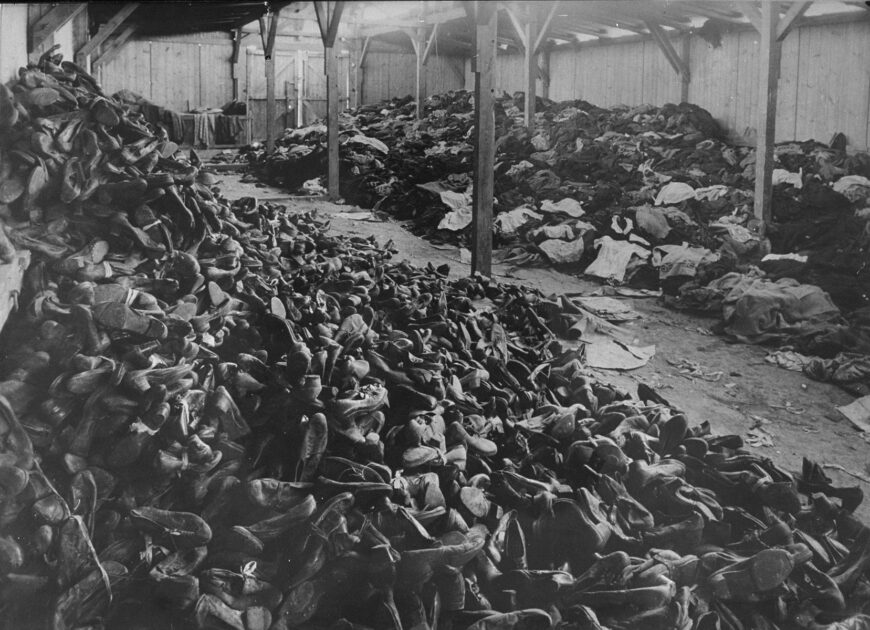

Auschwitz warehouse of shoes and clothing confiscated from prisoners and deportees gassed upon their arrival, still photo #15330 from Soviet film of the liberation of Auschwitz, First Ukrainian Front, shot after January 1945 (photographic print held by Comite d’histoire de la dieuxieme guerre mondiale, Paris, reproduced by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington)

Existential questions

Growing up, Boltanski was influenced by the dominant philosophy of the time. Following the devastating destruction of World War II, the Holocaust, and atomic bombs, Existentialism became highly influential among European intellectuals. The writings of French thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Simone de Beauvoir and others harshly critiqued the ideals of the Enlightenment, which had thus far been considered the bedrock principles of European and American modernity. In the post-war period, the Enlightenment values of the essential nobility of the human body and mind, rationality, progress, redemption, and the crucial role of posterity in enhancing human legacies were challenged in favor of the primacy of individual free will. For the Existentialists, the dark reality of the war, the bombs, and the Holocaust shattered the traditional belief in destiny, replacing it with the unsettling notion of chance and the dismantling of the inevitability of progress. This worldview made a permanent impact on Boltanski’s creative work.

The repeated references to the Holocaust during his formative years were responsible for Boltanski’s sustained interest in human mortality, which characterizes much of his work. Unlike most other genocides, the Final Solution designed by the Nazis employed a highly organized archival system to both dehumanize its victims and generate meticulous historical records of the atrocities. Tattooing each prisoner with a number, classifying them into groups by skill set while eliminating those it deemed useless, and accumulating their confiscated possessions—clothing, baggage, shoes, eye-glasses—in separate groups with plans for future use were some of the strategies that made the attempted extermination a remarkably efficient bureaucratic project.

Christian Boltanski, Personnes, 2010, Grand Palais, Paris, Monumenta 3 (photo: tangi bertin, CC BY-SA 2.0) © estate of the artist

Personal archive

Without any formal schooling in art, Boltanski, too, made the archival principle central to his art. For him, artifacts left behind had the potential to be a personal archive; such objects, he claimed, evoked the absent subject. He therefore regarded albums of family photographs, clothing or any such possessions as components of a biography waiting to be reconstructed. Underscoring the loss of biography by focusing on archival remains that were disassociated from their origins was important to Boltanski and an expression of his interest in the fragility of memory. It was his way of restoring the erased humanity of victims of collective traumas. His attraction to the archive, along with his exploration of the complex relationship between individual identity and the human multitude, and his interest in the role of chance in life and death converge into Personnes, his largest installation.

Personnes, however, has a precedent in an installation series from 1988. In one version called Reserve Canada, Boltanski hung used garments on the walls of a chamber from floor to ceiling. The title “Canada” has a dark origin. In the Nazi camps, selected Jewish prisoners, known as the Sonderkommandos, were forced to cremate the bodies of those who were murdered in the gas chambers or bury them in mass graves and store their possessions. It is believed that these forced laborers invented the name “Canada” (or Kanada”)—possibly a tragically ironic euphemism for an imagined land of plenty—to refer to the warehouses containing the belongings of the deceased. Thus, while the scene initially appears to be a second-hand clothing store, knowledge of the title’s background promptly changes that perception. Because Boltanski believed every individual is unique with possibilities, he was intrigued by the anonymity of individual identities within a collective trauma. A dress, like a photograph, is both a reminder of the absence of its owner and an intimate object linked to the wearer’s body. Though each clothing item in Canada represents a person, that specificity is subsumed by the power of the multitude. This tension between individual and collective identities works much more powerfully in Personnes.

A contradiction

In French, “personnes” has two contrary meanings; depending on context, it can either mean “people” or “nobodies”. This opposing duality pervades the project. Unlike Reserve Canada, this installation with around fifty tons of clothes has an ominous ambience that affects many visitors. The crane repeatedly picking up garments from the mound and dropping them becomes a disturbing reference to the film footage shot by the Allied forces at the liberated concentration camps in 1945 of massive piles of corpses being loaded on trucks and bulldozed into mass graves. In fact, the separated rectangular spaces on the floor of the Grand Palais immediately recall such graves where bodies are commingled and individual existence is forever erased; a genocidal arena where one becomes “nobody.” What is more, Boltanski deliberately left the exhibition venue unheated because he wanted to exacerbate the unease of visitors in a Paris winter, aiming for a heightened psychological impact.

Rusted biscuit tins and human heartbeats draw attention to traces of individuality overwhelmed by their multiplicity. For Boltanski, the popular European practice of using empty biscuit containers to store memorabilia, money or other intimate possessions made them personal reliquaries with no public value. Thus, with each tin assigned a number, the wall of containers at the entrance of the gallery becomes a collective structure where individual biographies and memories become anonymous. Similarly, the sound of recorded heartbeats, the ultimate sign of a person’s life, is disconnected, anonymous, and impossible to distinguish from a myriad of other beating hearts.

Christian Boltanski, Personnes, 2010, Grand Palais, Paris, Monumenta 3 (photo: Giovanni Sighele, CC BY 2.0) © estate of the artist

Collective trauma

Belief in chance is perhaps Boltanski’s strongest link to Existentialism. Existentialists unequivocally rejected the view that the victims, including children, of the Holocaust or any other genocide were destined to die. Destiny was to them, a cruel, and more importantly, irrational position. Instead, chance became a dominant theme in their effort to understand collective traumas. Boltanski deeply reflected on the role of chance in life, including survivor’s guilt, where a survivor of a tragedy painfully wonders why they, and not the others, escaped death. The dominant component in Personnes that underscores chance is the action of the crane. While the mechanism resembles the robotic claw used to pick up stuffed dolls from a glass case at an arcade, its enormity in the installation makes it a dystopian giant toying with human remains—”the hand of God,” as Boltanski observed. Watching the crane’s repetitive action of randomly grabbing clothes and callously releasing them from its clutch, one becomes acutely aware of the active role of chance in the process, especially since the machine picks up a different quantity of clothes each time. Furthermore, while some of the stacked biscuit tins contain personal artifacts, a visitor never knows which ones do, as all of them are impersonally marked with a number.

Bearing traces of individual biographies, the tins and the clothes lend themselves to classification and documentation that is central to the fictive archival process that the artist asks us to imagine. The heartbeats, however, have already achieved archival status. Beginning in 2005, Boltanski recorded many thousands of heartbeats, meticulously organizing and cataloging the recordings with donor information. Around fifteen thousand of those recordings were used in Personnes. The collection eventually grew into the Heart Archives Project. Three copies were made of each recording, one of which was sent to a sponsored sanctuary on Teshima Island in Japan’s Inland Sea. Since 2010, the entire collection has been stored in a one-story building on the island especially made for it. This archive is the most powerful evidence of the artist’s meditations on absence, memory, and both the reality and abstraction of death.

After its display in Paris, adjusted versions of Personnes have since been reconstructed at several international venues, one of which was No Man’s Land, exhibited at the Park Avenue Armory in New York in the summer of 2010. A spectacle engaged in the act of remembrance, Personnes referentially evokes the Holocaust, but also explores broader questions around mortality. Through his lifelong curiosity about mortality and his creative attempts to reconcile the fragility of individual existence with the certainty of death, Boltanski never surrendered to morbidity and pessimism. Once one experiences the harshly dystopian character of Personnes, one realizes that by dissecting the uneasy question of death, the artist, in fact, celebrates Humanity and every individual’s place in it. He was always ready to let things go, including his art. Boltanski required his projects to be dismantled at the end of the show because he wanted his narratives and ideas to outlive the objects.

Additional resources

Marian Goodman Gallery, New York

Christian Boltanski, Reserve Canada at the Marian Goodman Gallery